Meeting the artist Ryoji Ikeda for the Financial Times, 29 November 2019

At breakfast in a Paris café, the artist and composer Ryoji Ikeda looks ageless in a soft black cap and impenetrably dark glasses, dressed all in black so as to resemble the avatar from an indie video game.

His work too is severe, the spectrum reduced to grayscale, light to pixels, sound to spikes. Yet Ikeda is no minimalist: he is interested in the complexity that explodes the moment you reduce things to their underlying mathematics.

An artist in light, video, sound and haptics (his works often tremble beneath your feet), Ikeda is out to make you dizzy, to overload your senses, to convey, in the most visceral manner (through beats, high volumes, bright lights and image-blizzards) the blooming, buzzing confusion of the world. “I like playing around with the thresholds of perception,” he says. “If it’s too safe, it’s boring. But you have to know what you’re doing. You can hurt people.”

Ikeda’s stringent approach to his work began in the deafening underground clubs of Kyoto. There, in the mid-1990s, he made throbbing sonic experiences with Dumb Type, a coalition of technologically adept experimental artists. And he can still be this immediate when he wants to be: visitors to the main pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale found themselves squeezed through “Spectra III” (first assembled in 2008), a white corridor so evenly and brightly lit your eyes rejected what they saw, leaving you groping your way out as if in total darkness.

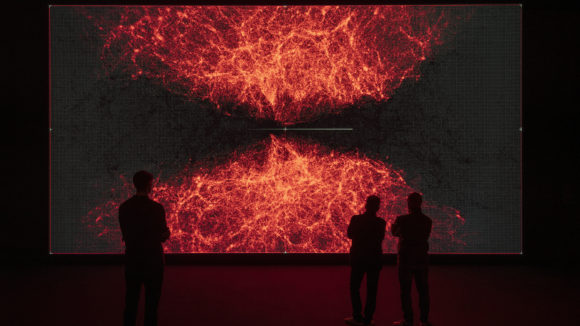

These days, though, he is better known for installations that go straight for the cerebral and mathematical. His ongoing “data-verse” project consists of three massively complex computer animations. The first part, “data-verse 1”, is based on static data from CERN, Nasa, the Human Genome Project and other open sources. “data-verse” contains animations, tables, graphs, matrices, 3D models, Lidar projections, maps. But what is being depicted here: something very small, or very big? There’s no way to tell. The data have peeled away from the things they represent and are dancing their own pixelated dance. Numbers have become rivers. At last the viewer’s mind surrenders to the flow and rhythm of this frenetic 12-minute piece.

It would be polite to say that “data-verse” is beautiful — but it isn’t. Rather, it is sublime, evoking a world stripped back to its mathematical bones. “If it’s beautiful, you can handle it; the sublime, you cannot,” Ikeda says. “If you stand in some great whited-out landscape in Lapland, the Sahara or the Alps, you feel something like fear. You’re trying to draw information from the world, but it’s something that your brain cannot handle.”

Similarly, the symmetrical, self-similar “data-verse” is an artwork that your mind struggles to navigate, tugging at every locked door in an attempt to regain purchase on the world.

“You try to understand, but you give up — and then it’s nice. Because now you are experiencing this piece the same way you listen to music,” Ikeda says. “It’s simply a manipulation of numbers and relationships, like a musical composition. It’s very different from the sort of visual art where you’re looking through the surface of the painting or the sculpture to see what it represents.”

When we meet, Ikeda is on his way to Tokyo Midtown, and the unveiling of “data-verse 2” (this one based on dynamic data “like the weather, or stock exchanges”). The venue is Beyond Watchmaking, an exhibition arranged by his patron, the eccentric family-run Swiss watchmaker Audemars Piguet. The third part of data-verse is due to be unveiled next year.

It is a vastly ambitious project but Ikeda has always tended towards the expansive. He pulls out of his suitcase an enormously heavy encyclopedia of sonic visualisations. “I wanted you to see this,” he says with a touching pride, leafing through page after page of meticulously documented oscilloscoped forms. Encyclopedia Cyclo.id was compiled with his friend Carsten Nicolai, the German multimedia artist, in 1999. Each figure here represents a particular sound. The more complex figures resemble watch faces. “It’s for designers, really,” Ikeda shrugs, shutting the book, “and architects.”

And the point of this? That lawful, timeless mathematics underpins the world and all our activities within it.

Ikeda spends 10 months out of every 12 travelling: “I really work in the airport or the kitchen. I don’t like the studio.” Months spent working out problems on paper and in his head are interspersed with intense, collaborative “cooking sessions” with a coterie of exceptional coders — creative sessions in which all previous assumptions are there to be challenged.

However, “data-verse” is likely to be Ikeda’s last intensely technological artwork. At the moment he is inclining more towards music and has been arranging some late compositions by John Cage in a purely acoustic project. As comfortable as he is around microphones, amps and computers, Ikeda isn’t particularly affiliated to machines.

“For a long time, I was put in the media-art category,” he says, “and I was so uncomfortable, because so much of that work is toylike, no depth to it at all. I’m absolutely not like this.”

Ikeda’s art, built not from things but from quantities and patterns, has afforded him much freedom. But he is acutely aware that others have more freedom still: “Mathematicians,” he sighs, “they don’t care about a thing. They don’t even care about time. It’s very interesting.”