Caspar Henderson writes beguiling commonplace books about the natural world, full of eye-catching detail and plangent commentary. His Book of Barely Imagined Beings: A 21st Century Bestiary came out in 2012. A Book of Noises is a worthy companion: a pursuit of auditory wonders, a paean to the act of listening, and a salute to silence.

Item: the music of the spheres. (The planets’ orbits, proving unideal and elliptical, suggested to the musically-minded astronomer Johannes Kepler an appropriately sad, minor-keyed Leitmotif for the Earth, “where, he felt, misery and famine held sway.”)

Item: the world’s loudest sound. (The asteroid Chicxulub, that killed the dinosaurs 66 million years ago; also an honourable mention to the Indonesian volcano Karakatoa, whose eruption in 1883 burst eardrums forty miles away).

Bees (playful). Frogs (ardent). Bats (unbelievably loud). The Magic Flute and the soundscapes of Hell. Sounds of the cosmos give way to sounds of the Earth. Life follows, bellowing, and humanity comes after, babbling and brandishing bells. The 48 forays into sound that make up A Book of Noises are arranged with the sort of guileless simplicity achievable only after the author-compiler has been beating their head against a wall for some years.

Everything trembles. The world sounds and resounds. Elephants flee the sound of helicopter blades turning eighty miles away. The root system of the common pea plant will move towards the sound of water in a pipe.

There’s something missing. If ever a book cried out for an accompanying Spotify playlist, it’s this one. Maybe I was looking too soon. Maybe a kind reader will put one together. What the heck, maybe I will. Ransacking this book affords hours of listening pleasure (or at any rate bemusement). Max Richter’s album Sleep to ease us in. Then Sam Perkins’s Alta for Two String Trios and Electronics, capturing the ephemeral crackles that sometimes accompany the Northern Lights. Dai Fujikura’s 2010 Glacier, which the composer describes as “a plume of cold air which is floating silently between the peaks of a very icy cold landscape, slowly but cutting like a knife.” Joseph Monkhouse’s soundscapes of the Somerset levels in the Iron Age. David Rothenberg’s quixotic saxophone duets with whales in 2008 stretched even Henderson’s famous generosity of spirit, and he writes: “it is hard to know how far, if at all, the whales are actually listening.” Such grounding moments are important, in a book chock-full of fancy.

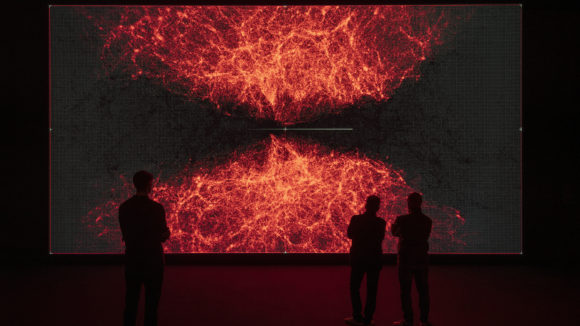

The point is, the world makes sounds and we, at our best, make sounds of our own in response. For every natural wonder, there is probably an eccentric musical instrument gathering dust somewhere: for every frog, a flute; for every booming volcano, some variation on a horn. The sounds that humans make are rooted in a profoundly material soundworld. The extrapolated and bizarre soundworlds made possible by digital technology are still largely terra incognita, and there may be good reason for this. “One is humbly aware that [this digital soundworld] will only be conquered by penetration of the human spirit,” the British composer Jonathan Harvey is quoted as saying, “and that penetration will neither be rapid or easy.”

Music itself, as a technology and as an idea, sometimes imposes too narrow a filter over our experience of sound. In a striking (ha!) chapter on bells, Henderson explains that the bells in Russian churches are meant to be voices, not musical instruments. For that reason, they are quite deliberately untuned, so that they produce as many over- and undertones as possible.

Humanity at its worst, meanwhile, makes a din that deafens whales and stresses birds out of their minds and mating patterns. Henderson cites soundscape ecologist Bernie Krause’s twenty-year project to record the sounds at Sugarloaf Park in California — a dramatic and frankly depressing record of environmental diminution and fragmentation, speaking to “a catastrophic loss of sonic diversity and richness worldwide.” The story of our scraping of the planet is also part of Henderson’s story. This is not an altogether happy book.

Is it a wise one? This is Henderson’s clear and laudable ambition. One of the perils of writing a book like this is that, in order to make the contents readable in any order, you have to carefully top and tail every one of those forty-eight seemingly disconnected microchapters. The effort throws up gnomic and occasionally ponderous capstones that are a gift to the mean and cantankerous critic. In my notes here, the following closers: “Life calls to us even as we call to it.” / “If there is to be a future worth living in it will surely hold a place for re-enchantment.” / “While you live, shine.”

This sort of niggle only shows up on a fast read. Readers can and should take their time. It will be very well spent.