I’m writing some biographical sketches of Soviet scientists and academicians

Aleksandr Aleksandrovich Bogdanov, philosopher (1873–1928)

The moment he stepped off the boat, Lenin went on the offensive: “I know, Aleksey Maximovich, you’re always wanting to reconcile me with those Machists. I told you in my letter it’s pointless, so don’t even try.”

For months, the writer and political activist Aleksey Maximovich Peshkov – better known as Maxim Gorky – had been trying to bring the twin stars of the Bolshevik movement back together. Aleksandr Bogdanov was already staying with Gorky at his residence on the mediterranean island of Capri, once the favourite resort of Roman emperors. Valdimir Lenin had a standing invitation tovisit. The men had once been the closest of friends. Bogdanov had helped Lenin through his split with Trotsky, and the consequent crisis in the party, and between 1906 and 1907, while hiding out in Finland, Bogdanov, Lenin and his family had lived practically out of each others’ pockets.

But as the forces of reaction dismantled the gains of the 1905 uprising, Bogdanov and Lenin had grown further and further apart. Lenin still held out hope that the Bolshevik cause might be furthered within the Duma – the constitutional parliament established in 1905. Bogdanov thought this was a waste of time. His radical politics had been acquired during his first Tsarist exile, while delivering lectures to factory workers; he wanted the Bolsheviks to align themselves much more strongly with the old underground workers’ organisations.

The disagreement between Lenin and Bogdanov was a crucial one for the Party, and the men’s more or less equal standing only made things worse. Bogdanov – likeable, gentle, and a little bit full of himself – was also a loose cannon, preaching revolution for its own sake, as man’s only significant form of self-assertion. And he was extraordinarily good at getting hold of money. The Bolsheviks’ sometimes terroristic “expropriations” of funds from political opponents, and from the districts that harboured them, were Bogdanov’s idea. Bogdanov held the party’s purse-strings; since 1907, Lenin had found it harder and harder to fund his own projects.

Immediate and violent action might have drawn the two men together under the banner of a common cause – but there was no action to be had. With the decision to work within the Duma, 1905’s exciting world of barricades and mutinies had to be given up, and Bogdanov bitterly resented the fact.

The Bolsheviks seemed to be getting further and further away from any real action. In typical Chekhovian style, their factional arguments grew ever more rarefied. One contemporary memoirist wrote: “When Ilyich began to quarrel with Bogdanov on the issue of empiriomonism, we threw up our hands and decided Lenin had gone slightly out of his mind.”

Bogdanov, the son of a rural teacher, was an urbane thinker. He had read his Kant. He followed the theories of Ernst Mach and Richard Avenarius. He admired Marx, but he did not believe that Marx should have the last word on every topic. Above all, he understood that the sciences of mind lagged painfully far behind the physical sciences. So it was important to be as honest as possible about where one’s information about the world was coming from. The Austrian physicist Ernst Mach had pointed out that, real as the world may be, we can never apprehend it directly: our knowledge of it comes through our senses. Bogdanov’s “Machism” was an attempt to apply that honest admission consistently across all bodies of knowledge—

Bogdanov knew far more than was good for him: that afternoon in May 1908, as he vainly tried to explain his position, he stumbled over his words.

“Drop it,” Lenin snapped.

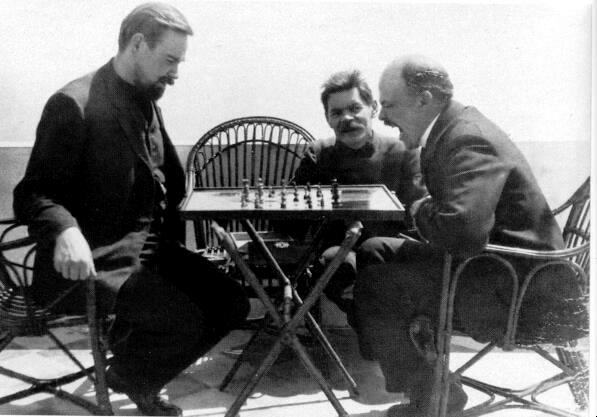

Perhaps it was Gorky who suggested a friendly chess game to clear the air. At any rate, he is there in the photograph, looking on as Lenin, seated on a balcony with his back to the Tyrrhenian Sea, steadily loses control of the game, and himself. It astonished Gorky how angry and childish he became.

Lenin believed in Marx. He believed in the natural sciences. He believed that some things had been discovered once and for all. He was no philosopher, and he imagined that Bogdanov was a dangerous relativist. Bogdanov believed in nothing and so, whether he knew it or not, he was siding with the priests and the mystics. “Somebody or other – Juarez, I think – said, ‘It is better to speak the truth than be a minister.’ Or a Machist, I would add.”

Aleksandr Bogdanov had always revered Lenin, but the differences between the men were becoming unbridgeable. Bogdanov was the more intellectually adept of the two, but he lacked Lenin’s appetite for political infighting. Bogdanov was a novelist: his science fantasy Red Star was being published that year, and he hankered for more writing time.

Bogdanov and the others went out for a walk, and Lenin unburdened himself to his hostess, Gorky’s common-law wife, Maria Andreyeva. Of Bogdanov and his set, Lenin said, more in sorrow than in anger, “They are intelligent, talented people. They have done a great deal for the Party, they could do ten times more, but they won’t go with us! They can’t. Scores and hundreds like them are broken and crippled by this criminal system.”

With hindsight, it’s clear enough that Bogdanov’s philosophy foreshadows the greatest achievements of Soviet science in the first half of the twentieth century. Marxism’s greatest intellectual challenge was to to make room for human experience, while at the same time doing away with God. It wasn’t enough to be crudely materialist, because Mind wasn’t a thing. You couldn’t point to it the way you could point to a chair or a table. And you couldn’t make mind a special case, either, because that led straight to mysticism. Mind, therefore, had to be an “emergent property” – something that arose, not from matter itself, but from the way matter was organised.

Bogdanov’s breakthrough was to realise that this is true of everything. Everything is as it is because it is arranged in a certain way. If you understand how something is organised, then you understand its essence. If you can describe things in terms of their organisation, then you really can talk about human minds and even whole societies in the same breath as chairs and tables, since all these things are simply more or less complex arrangements of matter. Bogdanov envisaged a science which would embrace the biological and social worlds in the way that mathematics had described classical mechanics. In the West, we call this science “systems theory”: our entire digital culture is built upon it.

It has been said that Russian philosophy has a Messianic streak a mile wide, and Bogdanov’s writings certainly lend credence to the claim. Bogdanov attempted to apply what was essentially a scientist’s philosophy over the whole of human experience. He believed that the world’s “biological-organisational” tendencies could and should be mastered to control human society on an economic, political, psychic, and even sexual level. Bogdanov’s schemes were at once grander and vaguer than Marxism itself. They were – or seemed to be – wildly impractical. No wonder, then, that come the October Revolution, and the Bolshevik takeover of the State, Lenin was prepared to tolerate his old friend’s “infantile” social experiments.

Following his visit to Capri, Vladimir Lenin had split from Bogdanov and his followers. He had attacked Bogdanov’s work in print and in person, and had him expelled from the party. Bogdanov had responded by walking away with the Bolsheviks’ monies, and using them to set up an experimental revolutionary school on Capri with his brother-in-law, Anatoly Lunacharsky. The experiment had faltered. By 1917, Bogdanov’s ambition to manufacture and manage a truly proliterian culture must have seemed a harmless dream – harmless enough that Lenin appointed Bogdanov’s co-experimenter Lunacharsky Commissar of Education, charged with the development of Soviet culture as well as its learning. Lunacharsky, in turn, made room for his brother-in-law’s ‘Proletkult’ experiment: an attempt to bootstrap an entire proliterian culture out of little more than a heap of good intentions.

Incredibly, it succeeded. At its height, Bogdanov’s cultural movement boasted 400,000 members, published twenty journals, and had won the public allegiance of virtually every significant artist, musician and writer in Russia. Experimental art, music and theatre flourished. The Tula Proletkult music section had a symphony orchestra, a brass band, an orchestra for folk instruments, and special classes in solo and operatic singing. Even tiny arctic Archangel, perched on the coast of the White Sea, boasted a choir. Lunacharsky greeted Proletkult’s meteoric rise with bemusement; Lenin’s reaction was one of barely-disguised horror. He insisted Lunacharsky’s Commissariat take over the running of the Proletkult: the Commissariat itself was closed down soon after. Now that the Bolsheviks were in power, Bogdanov’s anarchic inclinations could no longer be indulged.

Like many an intellectual who followed him into semi-obscurity, Bogdanov responded by devoting his time to his writings, and to science. In 1924, he began to investigate scientifically a folk idea about blood that had cropped up once or twice in his science fiction: the idea that transfusions might rejuvinate the body. His studies were perfectly serious: in 1925-1926, he founded the Institute for Haemotology and Blood Transfusions, which was later named after him. But here too, and critically, Bogdanov’s ambition got the better of him: on 7 April 1928 he died following a transfusion of infected blood.