for The Guardian, 2 November 2016

At this year’s Ars Electronica festival in Linz, Austria, I happened upon a robot made of hacked and 3D-printed surgical components that can perform DIY keyhole surgery. Its builder, the Dutch artist Frank Kolkman, was inspired by YouTube videos in which impoverished hackers and makers, largely without insurance, share medical tips and tricks. No money for bridgework? Try Sugru moldable glue.

A revolution is afoot in medicine. And like all revolutions, it is composed of equal parts inspirational advance and jaw-dropping social catastrophe. On the plus side, there are the health and fitness promises inherent in the artefacts of a personal health surveillance industry – all those Jawbones and Fitbits and Scanadu Scouts, iPhones and Apple Watches – that promises to top $50bn in annual sales by 2018. The devices aren’t particularly accurate (yet), and more than half of them end up at the bottom of a drawer after six months. Still, DIY devices are already spotting medical problems before their users do, raising the likelihood of a future in which illness and medical conditions are treated long before the patient gets sick.

On the minus side, there is Kolkman’s terrifyingly practical robot, and its promise of a future in which DIY medicine is the only medicine the ordinary individual can afford. The sunny west coast self-reliant rhetoric of the “making” and “hacking” and “quantified self” movements disguise the disturbing assumption that they can be a substitute for civic life.

We have been here before. Not much more than a century ago the Russian empire was a ramshackle agglomeration of colonies, held together by military force and hooch. There were no institutions for reformers to reform: no councils, no unions, no guilds, no professional bodies, few schools, few hospitals worth the name; in many places, no roads.

The responsibility for improvement and reform inevitably fell on the individual. Utopia was a personal quest in Nikolay Chernyshevsky’s novel What Is to Be Done? – according to Lenin, “the greatest and most talented representation of socialism before Marx”. Even more hysterical, Tolstoy’s The Kreutzer Sonata prefers the prospect of human annihilation to its current unreformed (read: lustful) condition. Outside the library and drawing room, pre-revolutionary Russia floundered in a sea of cults, from machinism and robotism to primitive reticence, antiverbalism, nudism, social militarism, revolutionary sublimation, suicidalism … One outfit called itself the Nothing, its members neither writing, reading or speaking.

Into this stew came the railways and the clock and all of a sudden self-regulation became easy and practical. In Leningrad in 1923, a theatre critic, Platon Kerzhentsev, founded the League of Time, in order to promote time-efficiency. Eight hundred “time cells” were set up in the army, factories, government departments and schools. The “Timists” carried “chronocards” in order to monitor time-wasting, wasted motion and lengthy speeches. Without watches, they tried to guess the passage of minutes and hours, and were awarded medals for spontaneous “time discipline”. They kept meticulous diaries of their every daily action. Lenin had the league’s personal productivity posters pasted up on the wall behind his desk.

“Man will finally begin to really harmonise himself,” Leon Trotsky prophesied in 1922: “He will put forward the task to introduce into the movement of his own organs – during work, walk, play – the highest precision, expediency, economy, and thus beauty.”

The poet Alexei Gastev – whose forbidding toothbrush-moustache and crew cut concealed a lot of mischief – took Trotsky at his word. He built a “social-engineering machine”. This giant structure of pulleys, cogs and weights was a thing of no fathomable use whatsoever, yet Gastev insisted that a few hours’ workout would turn you into a new kind of human being. He rolled these machines out across the young Soviet Union, as a sort of mascot for his Central Insitute of Labour which, with Lenin’s personal backing, taught peasant workers how to behave in modern factories. A class at the Central Institute of Labour was a sort of drill practice: pupils stood before their benches in set positions, with places marked out for their feet. They rehearsed separate elements of each task, then combined them in a finished performance. (Judging by the sheer popularity of the classes, and the speed of the institute’s expansion, the classes must have been quite enjoyable.)

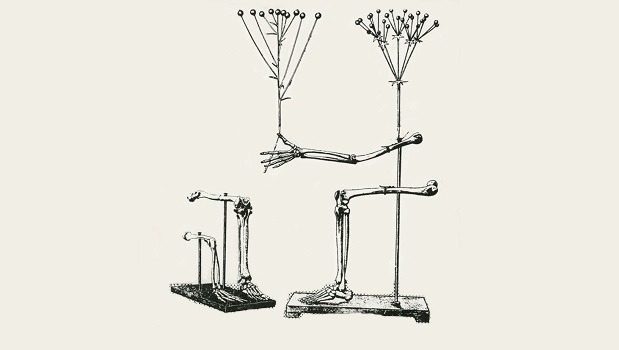

Joining Gastev at the beginning of his career was the young Nikolai Bernstein, whose childhood spent assembling radios and building models of steam engines and bridges, set him in good stead when it came to mechanically registering the movements of the human body. He developed a high-speed camera called the kymocyclograph. The shutter, a round plate with holes in it, rotated before the camera lens, so that the photographic plate would record multiple images, each exposed a fraction of a second after its neighbour. (Motion-capture cinema, VR – and all the other technologies that keep Gollum actor Andy Serkis on the talkshow circuit – begin here.)

By the end of these studies, Bernstein had good evidence that motion could not be a simple matter of Pavlovian “reflexes”. His more nuanced model of motor responses amounted to a fully fledged theory of cybernetics, decades before Norbert Wiener coined the term in 1948.

The early Soviet Union gathered unprecedented amounts of data on human motion, fitness, behaviour and genetics, making it a world leader in the field. A new kind of human being – healthy, fit, psychologically integrated and free of heritable disease – seemed, for a few heady days in the 1920s, an achievable aspiration.

Then, in 1927, a miner called Alexey Grigoryevich Stakhanov went to work in a mine. He was no superman, but he was energetic and intelligent, and he could see ways of organising his work crew to increase the amount of coal they were able to dig in a single shift. On 31 August 1935, it was reported that he had mined a record 102 tonnes of coal in four hours and 45 minutes – 14 times his quota. Barely three weeks later, on 19 September, Stakhanov and his crew more than doubled this record.

Others rushed to follow Stakhanov’s example, and newspapers and newsreels across the Soviet Union celebrated their efforts. In Gorky, a worker in a car factory forged nearly 1,000 crankshafts in a single shift. A shoemaker in Leningrad turned out 1,400 pairs of shoes in a day. On a collective farm, three female “Stakhanovites” proved they could cut sugar beet faster than was thought humanly possible. Such workers were awarded higher pay, better food, access to luxury goods and improved accommodation. Stakhanovism soon became a mass movement. “In factories and even in scientific institutes,” wrote the American psychologist Richard Schultz, “the workers’ names may be posted on a bulletin board opposite a bird, deer, rabbit, tortoise or snail relative to the speed with which they turn out their work. A great deal of prestige is attached to the ‘shock brigade’ worker.”

For as long as human beings labour for others, their lot will improve only so far as their productivity rises. Investment beyond this point makes no sense. The Soviet Union of the 1920s was an impoverished state dotted with institutes of labour, health and maternity clinics, mental health services, housing offices and countless censuses. Coming to power at the end of the decade, Joseph Stalin replaced all this social engineering with, well, engineering. Magnitostroi, which is still the largest steelworks in the world, housed its workers in tents downwind of the chimneys. The construction of the White Sea Canal cost 12,000 lives – around a 10th of the workforce.

Drunk as we are on the illusion of personal control, we should remember that data trickles uphill toward the powerful, because they are the ones who can afford to exploit it. Today, for every worried-yet-well twentysomething fiddling with his Fitbit, there is a worker being cajoled by their employer into taking a medical test. The tests are aggregated and anonymised, and besides, the company is giving the worker a cut of the insurance savings the test will make. So where’s the harm?

Well, for a start, anonymising data is incredibly hard to do. The bigger the datapool, the easier it is to triangulate data sets and home in on an individual. And while people can get thrown in jail for this sort of thing, algorithms are a lot harder to police. Has the computer said “no” to your mortgage application? Well, sorry, but there may simply be no human to blame: the machine has figured things out on its own.

An even bigger worry is the way that, in our smartphone-enabled and meta-data-enriched world, complete knowledge of human affairs is becoming increasingly possible, making redundant the entire gamble of insurance. At that point the scope for individual self-determination shrinks to zero and we are living in the world of Andrew Niccol’s excellent 1997 film Gattaca.

Unregulated wellness programmes are begging to be used as tools of surveillance, and that’s not because anybody’s actually doing anything wrong. It’s because we have taken control of our own data, while at the same time forgetting that data ultimtely belongs to whoever can make the most use of it.

And it need not even be a problem, unless the class in power decide to replace social engineering with, well, engineering, health services with “making” and “hacking”, and civic societies with a desert, littered with the grinning skulls of people who aspired to west-coast “radical self-reliance” – and failed.