My leafy, fairly affluent corner of south London has a traffic congestion problem, and to solve it, there’s a plan to close certain roads. You can imagine the furore: the trunk of every kerbside tree sports a protest sign. How can shutting off roads improve traffic flows?

The German mathematician Dietrich Braess answered this one back in 1968, with a graph that kept track of travel times and densities for each road link, and distinguished between flows that are optimal for all cars, and flows optimised for each individual car.

On a Paradox of Traffic Planning is a fine example of how a mathematical model predicts and resolves a real-world problem.

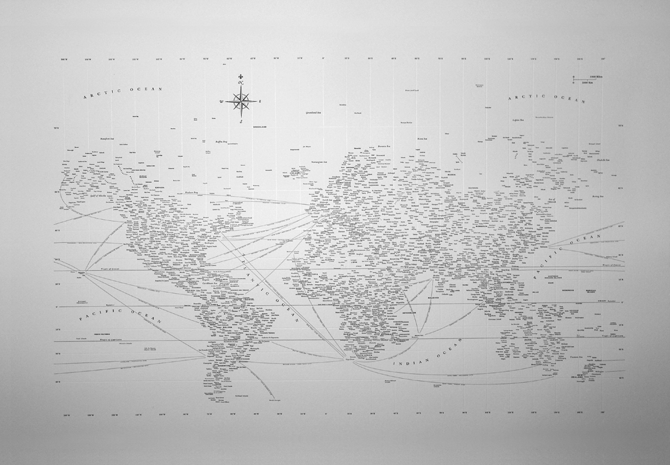

This and over 1,300 other models, maps and forecasts feature in the references to Katy Börner’s latest atlas, which is the third to be derived from Indiana University’s traveling exhibit Places & Spaces: Mapping Science.

Atlas of Science: Visualizing What We Know (2010) revealed the power of maps in science; Atlas of Knowledge: Anyone Can Map (2015), focused on visualisation. In her third and final foray, Börner is out to show how models, maps and forecasts inform decision-making in education, science, technology, and policymaking. It’s a well-structured, heavyweight argument, supported by descriptions of over 300 model applications.

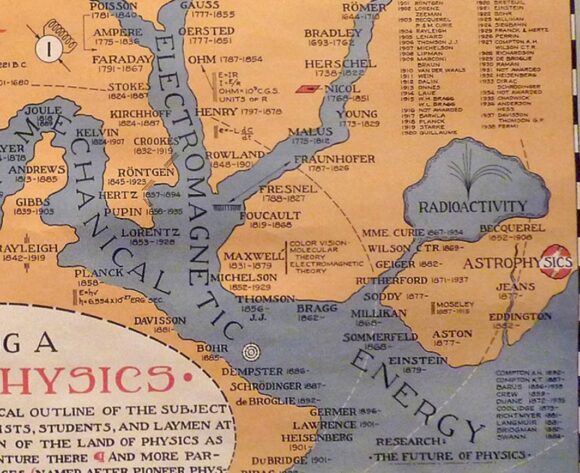

Some entries, like Bernard H. Porter’s Map of Physics of 1939, earn their place thanks purely to their beauty and for the insights they offer. Mostly, though, Börner chooses models that were applied in practice and made a positive difference.

Her historical range is impressive. We begin at equations (did you know Newton’s law of universal gravitation has been applied to human migration patterns and international trade?) and move through the centuries, tipping a wink to Jacob Bernoulli’s “The Art of Conjecturing” of 1713 (which introduced probability theory) and James Clerk Maxwell’s 1868 paper “On Governors” (an early gesture at cybernetics) until we arrive at our current era of massive computation and ever-more complex model building.

It’s here that interesting questions start to surface. To forecast the behaviour of complex systems, especially those which contain a human component, many current researchers reach for something called “agent-based modeling” (ABM) in which discrete autonomous agents interact with each other and with their common (digitally modelled) environment.

Heady stuff, no doubt. But, says Börner, “ABMs in general have very few analytical tools by which they can be studied, and often no backward sensitivity analysis can be performed because of the large number of parameters and dynamical rules involved.”

In other words, an ABM model offers the researcher an exquisitely detailed forecast, but no clear way of knowing why the model has drawn the conclusions it has — a risky state of affairs, given that all its data is ultimately provided by eccentric, foible-ridden human beings.

Börner’s sumptuous, detailed book tackles issues of error and bias head-on, but she left me tugging at a still bigger problem, represented by those irate protest signs smothering my neighbourhood.

If, over 50 years since the maths was published, reasonably wealthy, mostly well-educated people in comfortable surroundings have remained ignorant of how traffic flows work, what are the chances that the rest of us, industrious and preoccupied as we are, will ever really understand, or trust, all the many other models which increasingly dictate our civic life?

Borner argues that modelling data can counteract misinformation, tribalism, authoritarianism, demonization, and magical thinking.

I can’t for the life of me see how. Albert Einstein said, “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but no simpler.” What happens when a model reaches such complexity, only an expert can really understand it, or when even the expert can’t be entirely sure why the forecast is saying what it’s saying?

We have enough difficulty understanding climate forecasts, let alone explaining them. To apply these technologies to the civic realm begs a host of problems that are nothing to do with the technology, and everything to do with whether anyone will be listening.