Moving to Mars for New Scientist, 18 October 2019

Step into Moving to Mars, an exhibition of Mars mission and colony design at London’s Design Museum, and you are confronted, immediately, with some very good reasons not to move there. Minatory glowing wall texts announce that Mars was not made for you; that there is no life and precious little water; that, clad in a space suit, you will never touch, taste or smell the planet you now call “home”. As Lisa Grossman wrote for New Scientist a couple of years ago, “What’s different about Mars is that there is nothing to do there except try not to die.”

It’s an odd beginning for such an up-beat and celebratory show, but it provides some valuable dark ground against which the rest of the show can sparkle — a show that is, as its chief curator Justin McGuirk remarks, “not about Mars; this is an exhibition about people.”

Next up: a quick yet lucid dash through what the science-fiction writer Kim Stanley Robinson calls “the history of Mars in the human mind”. A Babylonian clay tablet and a Greek vase speak to our early cosmological ideas about the planets; a poster for the film Total Recall (the good one, from 1990), reminds us of Mars’s psychological menace.

The bulk of the show focuses on our current plans for the red planet. There are real space suits and models of real rovers, maquettes of 3D-printed Martian settlements and prototypes of Mars-appropriate clothing and furniture. Mission architectures and engineering sketches line the walls. Real hammers meant for the International Space Station (hollow, and loaded with ball bearings to increase their utility in zero-gravity) are wall-mounted beside a nifty low-gravity table that has yet to leave, and may indeed never leave, Earth. This, of course, is the great strength of approaching science through design: reality and speculation can be given equal visual weight, drawing us into an informed conversation about what it is we actually want from the future. Some readers may remember a tremendous touring exhibition, Hello Robot in 2017, which did much the same for robotics and artificial intelligence.

Half way round the show, I relaxed in a fully realised Martian living pod by the international design firm Hassell and their engineering partners Eckersley O’Callaghan. They’d assembled this as part of NASA’s 3D-Printed Habitat Challenge — the agency’s programme to develop habitat ideas for deep space exploration — and it combines economy, recycling, efficiency and comfort in surprising ways. Xavier De Kestelier, Hassell’s head of design technology and innovation, was on hand to show me around, and was particularly proud of the chairs here, which are are made of recycled packaging: “The more you eat, the more you sit!”

So much for the promise of Martian living. The profound limitations of that life were brought home to me a working hydroponic system by Growstack. Its trays of delicious cress and lettuce reminded me, rather sharply, that for all the hype, we are still a very long way from being able to feed ourselves away from our home world. We’re still at the point, indeed, where a single sunflower and a single zinnia, blossoming aboard the ISS — the former in 2012, the latter in 2016 — still make headlines.

The Growstack exhibit and other materials about Martian horticulture also marked an important cultural shift, away from the strategic, militarised thinking that characterised early space exploration in the Cold War, and towards more humane, more practical questions about how one lives an ordinary life in such extraordinary, and extraordinarily limited, environments.

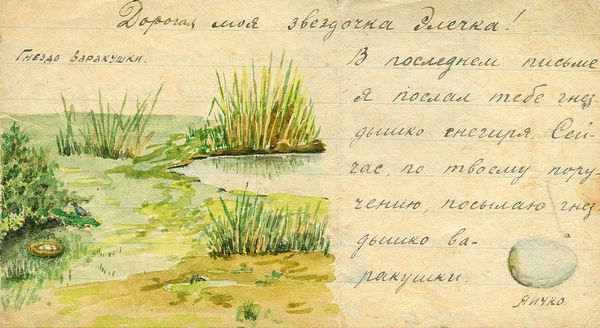

It’s no surprise that the Russian were thinking seriously about these questions long before the rest of us, and it was good to see Russian space cultures given their due in this impressively international show. All through the 19th century, researchers for the Tsarist government tried to develop agriculture in mostly frozen and largely infertile Siberia. Well into the Soviet era, soil scientists undertook extreme expeditions over vast distances in pursuit of insane agricultural speculations. It shows up in their popular culture. “Hold on, geologist,” ran one pop song of 1951, “hold out, geologist, you are brother of the wind and sun!” And then there are the films of Pavel Vladimirovich Klushantsev, born 1910 in St Petersburg.

Klushantsev’s documentary Road to the Stars (1957), a meticulous, scientifically accurate vision to the physics, engineering, ergonomics of space travel, was followed seven years later by Moon (1965), describing the exploration, mining, settlement and domestication of a new land. Both films feature succulent gardens glistening under space domes, and workers eager to tend them, and bowls full of peaches beside every workstation, offering a little, literal taste of home.

I was delighted to see here a screen showing *Mars* (1968), a much less celebrated effort — Klushantsev’s saturated, multicoloured vision of man on the Red Planet. It’s the film with the dog in the spacesuit: an image people who’ve never heard of this director treasure for its kitsch value. It’s the film that earned him a telegram which read: “Due to the low quality of your work, we hereby inform you that we are terminating your contract with the studio.”

So much for the Soviet imagination.

But other cultures, each with their own deep, historical motivations, have since stepped up with plans to settle Mars. My favourites projects originate in the Middle East, where subterranean irrigation canals were greening the desert a full millennium before the astronomer Percival Lowell thought he spotted similar structures on Mars. (The underground networks called khettaras in Morocco irrigated much of its northern oasis region right up until the early 1970s, when government policies began to favour dam construction.)

Having raised major cities in one of the most inhospitable regions on Earth — and this in less than a generation — we should hardly be surprised that the rulers of the United Arab Emirates believe it’s feasible to establish a human settlement on Mars by 2117. A development hub, “Mars Scientific City”, is scheduled to open in Dubai in the next three to four years, and will feature a laboratory that will simulate the red planet’s terrain and harsh environment. It will be, I suppose, a sort of extension of the 520-day Mars 500 simulation that in 2011 sent six volunteers on a round trip to the Red Planet without stepping out of the Russian Institute for Biomedical Problems in Moscow.

The playfulness of “Martian thinking” is quite properly reflected in this playful and family-orientated exhibition. The point, made very well here, is that this play, this freedom from strictures and established lines of thought, is essential to good design. Space forces you to work from first principles. It forces you to think about mass, and transport, and utility, and reusability. And I don’t think it’s much of a coincidence that Eleanor Watson, the assistant curator on this show, has been chosen to curate this year’s Global Grad Show, which in November will be bringing the most innovative new design thinking to Dubai — a city which, in contending with its own set of environmental extremes, often feels half way to Mars already.

As I was leaving Moving to Mars I was drawn up short by what looked like some cycling gear. Anna Talvi, a graduate of the Royal College of Art in London, has constructed her flesh-hugging clothing to act as a sort of “wearable gym” to counter the muscle wasting and bone loss caused by living in low gravity. She has also tried to tackle the serious psychological challenges of space exploration, by permeating her fabrics with comforting scents. Her X.Earth perfumed gloves “will bring you back to your Earth-memory place at the speed of thought”, with the the smell of freshly cut grass, say, or the smell of your favourite horse.

Those gloves, even more than that hydroponically grown lettuce, brought home to me the sheer hideousness of space exploration. It’s no accident that this year’s most ambitious science fiction movies, Aniara and Ad Astra, have both focused on the impossible mental and spiritual toll we’d suffer, were we ever to swap our home planet for a life of manufactured monotony.

There’s a new realism creeping into our ideas of living off-world, along with a resurgence of optimism and possibility. And this is good. We need light and shade as we plan our next great adventure. How else can we ever hope to become Martian?