You Belong to the Universe: Buckminster Fuller and the future by Jonathon Keats

reviewed for New Scientist, 11 June 2016.

IN 1927 the suicidal manager of a building materials company, Richard Buckminster (“Bucky”) Fuller, stood by the shores of Lake Michigan and decided he might as well live. A stern voice inside him intimated that his life after all had a purpose, “which could be fulfilled only by sharing his mind with the world”.

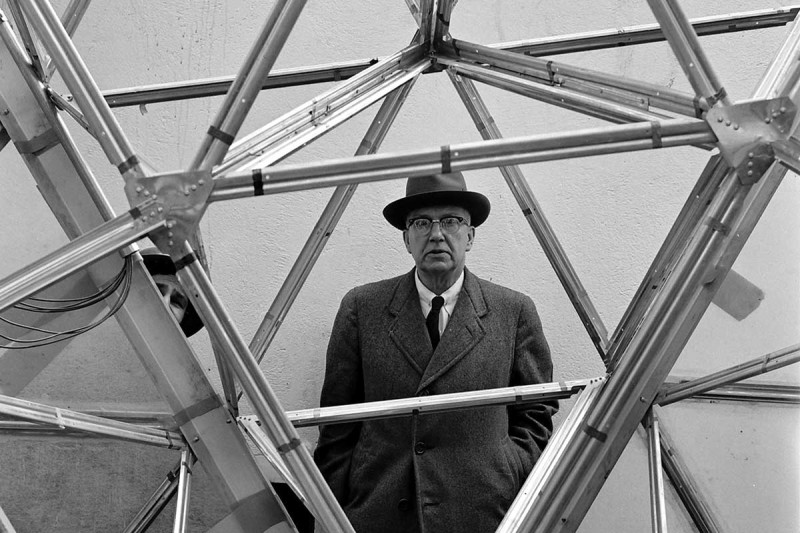

And share it he did, tirelessly for over half a century, with houses hung from masts, cars with inflatable wings, a brilliant and never-bettered equal-area map of the world, and concepts for massive open-access distance learning, domed cities and a new kind of playful, collaborative politics. The tsunami that Fuller’s wing flap set in motion is even now rolling over us, improving our future through degree shows, galleries, museums and (now and again) in the real world.

Indeed, Fuller’s”comprehensive anticipatory design scientists” are ten-a-penny these days. Until last year, they were being churned out like sausages by the design interactions department at the Royal College of Art, London. Futurological events dominate the agendas of venues across New York, from the Institute for Public Knowledge to the International Center of Photography. “Science Galleries”, too, are popping up like mushrooms after a spring rain, from London to Bangalore.

In You Belong to the Universe, Jonathon Keats, himself a critic, artist and self-styled “experimental philosopher”, looks hard into the mirror to find what of his difficult and sometimes pantaloonish hero may still be traced in the lineaments of your oh-so-modern “design futurist”.

Be in no doubt: Fuller deserves his visionary reputation. He grasped in his bones, as few have since, the dynamism of the universe. At the age of 21, Keats writes, “Bucky determined that the universe had no objects. Geometry described forces.”

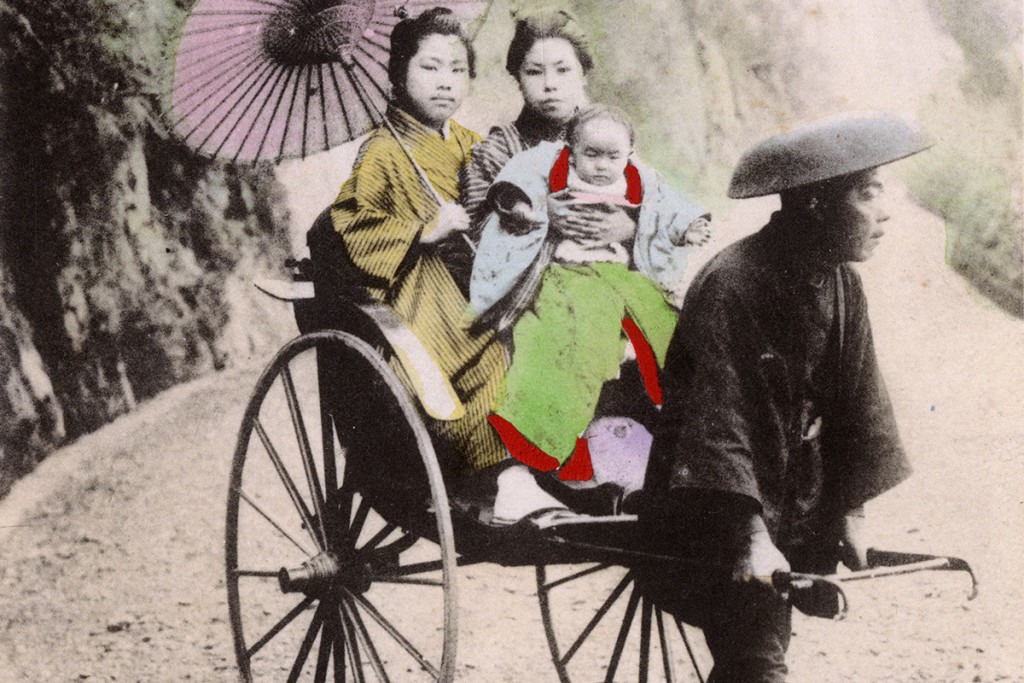

A child of the aviation era, he used materials sparingly, focusing entirely on their tensile properties and on the way they stood up to wind and weather. He called this approach “doing more with less”. His light and sturdy geodesic dome became an icon of US ingenuity. He built one wherever his country sought influence, from India to Turkey to Japan.

Chapter by chapter, Keats asks how the future has served Fuller’s ideas on city planning, transport, architecture, education. It’s a risky scheme, because it invites you to set Fuller’s visions up simply to knock them down again with the big stick of hindsight. But Keats is far too canny for that trap. He puts his subject into context, works hard to establish what would and would not be reasonable for him to know and imagine, and explains why the history of built and manufactured things turned out the way it has, sometimes fulfilling, but more often thwarting, Fuller’s vision.

This ought to be a profoundly wrong-headed book, judging one man’s ideas against the entire recent history of Spaceship Earth (another of Fuller’s provocations). But You Belong to the Universe says more about Fuller and his future in a few pages than some whole biographies, and renews one’s interest – if not faith – in all those graduate design shows.