A virus that robbed David Jane of his language and memory left him struggling to understand what had happened to him. His salvation was to recreate his condition on canvas. For New Scientist, 10 January 1998

DAVID JANE’s studio in south London is falling to pieces. Plaster has come

off the walls, revealing the wattling and brick beneath. Felt sags from a hole

in the roof. Every fractured surface frames another deeper, broken layer. It is

easy at first—and painful—to see parallels between the dereliction

of Jane’s studio and his paintings, which are based on magnetic resonance

imaging (MRI) scans of his own, damaged brain. “It can be a very heavy

experience to be drawing things that you know are inside you,” muses Jane. “They

look like animals—like they have separate lives.”

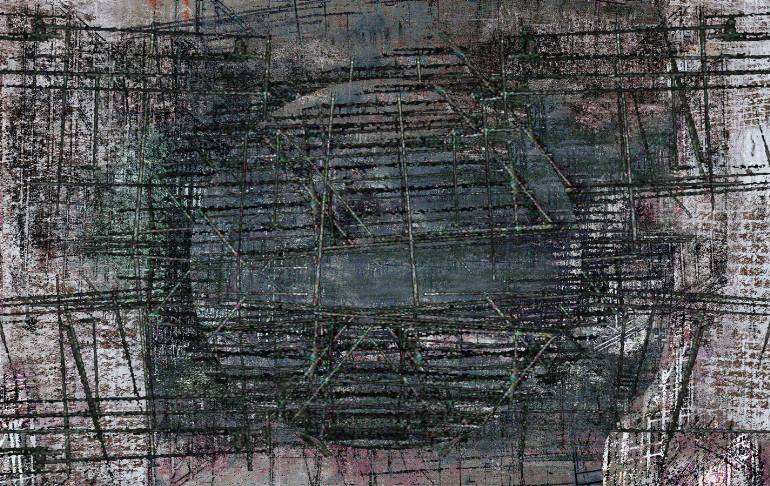

Jane calls his work self-portraiture, albeit of a unique, and at first

disturbing, kind. Wax surfaces bleed away to reveal other surfaces beneath.

These frames within frames reflect the way the medical scanner slices his brain

into a sequence of flat, two-dimensional images. But Jane’s fusion of art

and science is not about deterioration. It is about understanding—and more

than that, it is about recovery and regeneration.

Until 1989, Jane enjoyed a growing reputation as a painter. But that year,

while on holiday in Rio de Janeiro, he collapsed. When he woke up in London some

weeks later, he could not speak, write or recognise his family or himself. At

first he had no memory, and no awareness of the passage of time. Days, minutes,

months all seemed of equal duration, so that even when some memories did return,

he could make little sense of them. On one occasion he left the hospital in his

dressing gown and boarded a bus to visit his mother, who was dead. Much of his

recovery since then has been spent organising his experience into some kind of

sensible order.

What Jane didn’t know during his stay in hospital—what nobody could

tell him—was that he had contracted herpes simplex encephalitis. For

reasons that are still unknown, the virus has a predilection for certain areas

of the brain in some people. The body’s response is to dispatch immune cells to

the site of infection. This causes swelling which, together with the virus, can

kill off neurons and literally leave holes in the brain. In Jane, the virus

targeted the left temporal lobe, which is responsible for memory and

language.

Jane’s basic faculties began to return within a few weeks and he was able to

leave hospital. But it was not until June 1990—when new MRI scans were

taken—that he began to understand what had happened to him. Because he had

lost his language skills to the virus, Pat, his wife, realised that pictures

would be the easiest, most direct way of explaining to him what had happened. It

was she who first showed him the brain scans.

“The doctors were reluctant to show me them,” he remembers. “But the fact is,

I found them beautiful.” Jane could also see from the scans that the left-hand

side of his brain was different from the right. “So I began to understand what

had happened inside my brain.”

Jane began to use his skills as an artist to make simple ink and pencil

copies of the pictures he was shown. The copies were crude and amorphous,

literal reflections of the scans. But in the eight years since the virus struck,

Jane has made a remarkable recovery—and it’s all there in his work. His

drawings of tissue have given way to paintings that depict images of the mind

and then to full-scale exhibitions. Visceral and urgent, Jane’s images are an

amalgam of abstract style and biography, combined in ways which he could never

have imagined before his illness. And his originality is attracting attention:

the canvases have fired the enthusiasm of critics and collectors.

Jane’s growth as an artist has coincided with a burgeoning ability to face

hard truths. “I’ve been using a computer lately to manipulate some recent

scans,” he says. “It’s been depressing, seeing so clearly how much brain I’m

missing.”

The herpes infection left Jane inhabiting a very strange world. Just how

strange can be gleaned from the fact that he had to relearn many things from

scratch, such as the names of different parts of the body. His regained mastery

of speech is something he can largely credit to his son, Frank, who was born in

1991. The child’s appetite for bedtime stories gave Jane a perfect

reintroduction to words. Reading to his son, he acquired the language by easy

stages, as a child might.

Jane’s recovery is not total. Names still elude him, and reading is difficult

and slow. “Even manipulating images on a computer is taking me ages,” he laughs.

“I can’t follow the bloody menus.” Nevertheless, it is staggering how much he

has relearnt—and how he relearnt it. His damaged brain’s appetite for

learning continues to amaze him. “I remember I wanted to learn English,” he

says, “but what I ended up with at first was something completely different. The

spellings were all wrong, but they had this weird internal consistency. It was

as though my brain knew better than I did how to learn. It was rewiring itself

into a shape that suited itself. Me, I was just along for the ride.”

That sense of alienation—of surfing a healing wave over which he has no

control—has never entirely gone away. “I feel I have a relationship with

what’s inside of me,” he says. “Obviously I can’t actually separate `it’ from

`me’, but there is some sort of dialogue there.” Jane has learnt to harness that

dialogue in his work. “The distance I feel between my self and the brain I see

in the scans—I try to turn that into the distance that an artist has to

their subject,” he says.

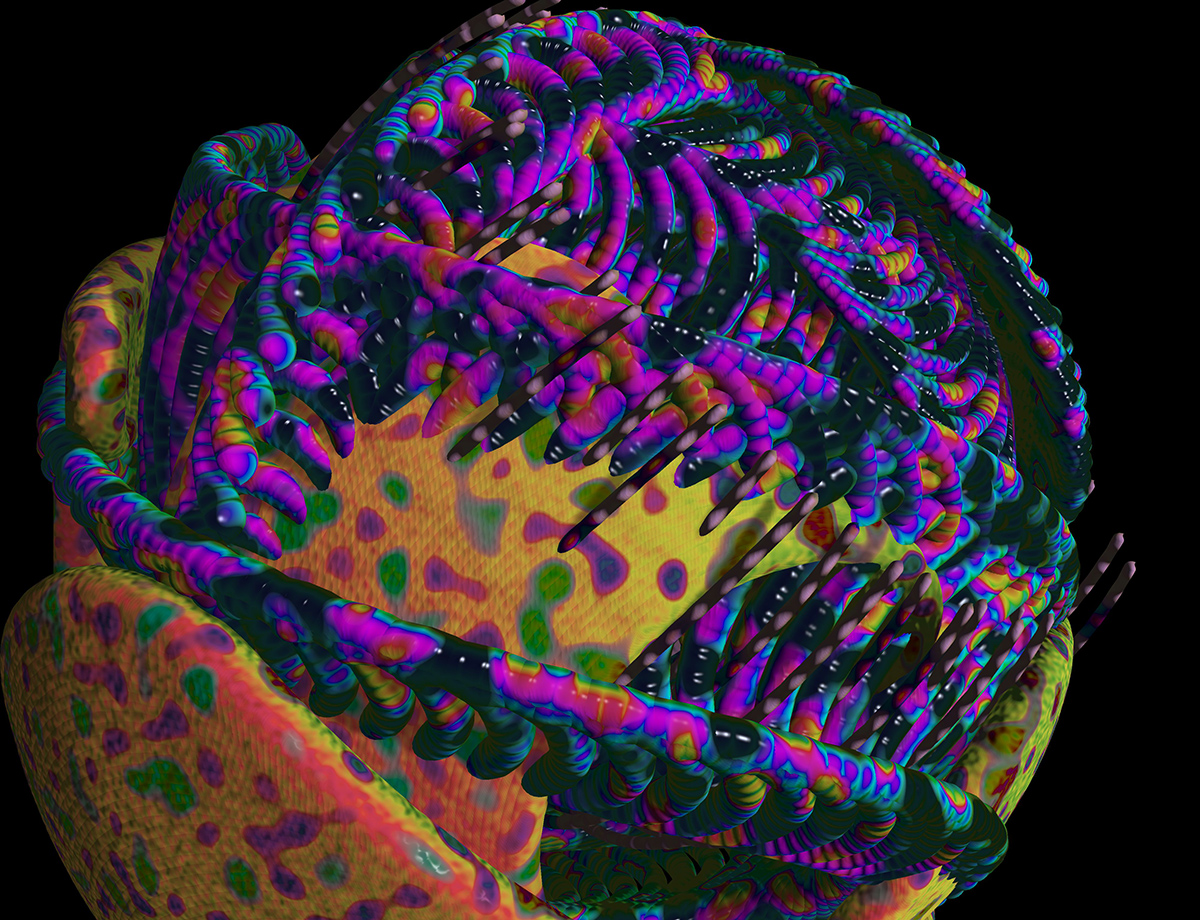

Over the past eight years he has continued to succeed at his task. As he got

better, the images from which he works—the scans

themselves—underwent remarkable technical improvement. Unlike the earliest

images of his brain, MRI today generates high-resolution colour pictures. These

advances have helped to fuel Jane’s imagination. “Over time, my paintings get

less and less like illustrations,” he explains. “These days you won’t find

literal correspondences between the paintings and the scans. On the other hand,

thanks to those scans, my understanding of what happened, and what each part of

the brain does, gets more and more precise.”

In 1994, Jane began to add solidity and texture to his works by painting in

wax. For a long time he has wanted to get rid of the signatures in his

work—the array of distinct brush strokes. “You don’t necessarily want to

put your emotion into every stroke,” he says. “The emotion belongs to the piece

as a whole.”

He has found a way to “draw with heat”, often burning holes in a painting

with a blowtorch. By putting several such sheets together, Jane mimics the

effect of looking at the scanned slices of his brain. Behind one layer of tissue

lies another. He turns the canvases as he works, forcing the wax to run in all

directions, creating images that echo the destruction of his own brain. “Looking

at the scans,” he says, “it’s clear my disease wasn’t very interested in

gravity. It moved freely in three dimensions. The damaged shape has a weightless

quality.”

In cultural terms, Jane sees his brand of portraiture, with its scientific

foundations, as a completely natural part of a continuing tradition. “I don’t

think there’s a clear distinction between art and science,” he says. “They

change at the same time.” This progressive partnership has been in evidence

since at least the 16th century, he says. He speaks with authority, although it

is a curious consequence of his condition that he cannot give the names of the

artists who would prove his point. Those memories are no longer there.

But he remains undeterred. His latest venture is also his most ambitious: a

collaborative exhibition with his neurologist, Michael Kopelman of St Thomas’

Hospital in London. Kopelman, together with Alan Colchester’s image-processing

team at the University of Kent in Canterbury, has taken a new series of scans of

Jane’s brain and created three-dimensional images of it. Jane intends to enlarge

these pictures to about 2 metres square and then work wax, pigment oil, charcoal

and other materials into the images to enhance their 3D appearance. Then he will

overlay pages of text taken from reports by doctors, critics and scientific

commentators, so the pictures become a palimpsest of experience and

interpretation.

“We can meld science and art together,” says Jane. “And we’ll do that not to

obscure what’s going on, or prettify it, but to make it clear. Dr Kopelman and I

want to open the doors of understanding into the scientific interpretation and

artistic vision of brain scan images, so that people can see them as things of

beauty as well as knowledge.”

For many critics, however, Jane’s work far exceeds these stated ambitions.

“When you look at David Jane’s work,” says Denna Jones, curator at the

London-based Wellcome Centre for Medical Science, “your reactions aren’t

anything to do with disease. It’s not even to do with that interest in

body-mapping you see so much of these days. It’s simply a continuation of

self-portraiture—part of a tradition five centuries old.” If the

18th-century painter William Hogarth had had access to the technology Jane uses,

“he’d probably have done the same thing”, says Jones.

Jane doesn’t disagree. “I was always considered an abstract artist and I

never felt happy with that,” he reflects. “I certainly can’t be called

`abstract’ now, at any rate. You can’t get more visceral than to paint your own

brain.”