To mark the centenary of Surrealism, this article in the Telegraph

A hundred years ago, a 28-year-old French poet, art collector and contrarian called André Breton published a manifesto that called time on reason.

Eight years before, in 1916, Breton was a medical trainee stationed at a neuro-psychiatric army clinic in Saint-Dizier. He cared for soldiers who were shell-shocked, psychotic, hysterical and worse, and fell in love with the mind, and the lengths it would go to survive the impossible present.

Breton’s Manifesto of Surrealism was, then, an inquiry into how, “under the pretense of civilization and progress, we have managed to banish from the mind everything that may rightly or wrongly be termed superstition, or fancy.”

For Breton, surrealism’s sincerest experiments involved a sort of “psychic automatism” – using the processes of dreaming to express “the actual functioning of thought… in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern.” He asked: “Can’t the dream also be used in solving the fundamental questions of life?”

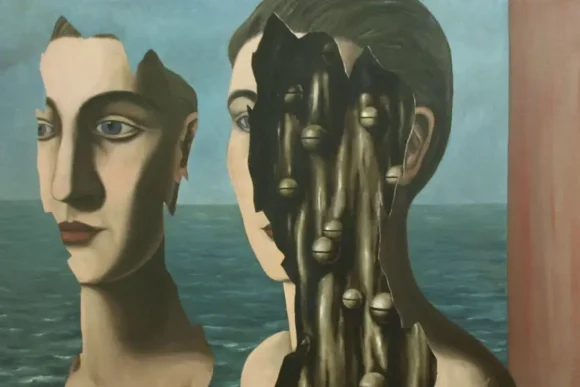

Many strange pictures appeared over the following century, as Breton’s fellow surrealists answered his challenge, and plumbed the depths of the unconscious mind. Their efforts – part of a long history of humans’ attempts to document and decode the dream world – can be seen in a raft of new exhibitions marking surrealism’s centenary, from the hybrid beasts of Leonora Carrington (on view at the Hepworth Wakefield’s Forbidden Territories), to the astral fantasies of Remedios Varo (included in the Centre Pompidou’s blockbuster Surrealism show.)

Yet, just as often, such images illustrate the gap between the dreamer’s experience and their later interpretation of it. Some of the most popular surrealist pictures – Dalí’s melting clocks, say, or Magritte’s apple-headed businessman – are not remotely dreamlike. Looking at such easy-to-read canvases is like having a dream explained, and that’s not at all the same thing.

The chief characteristic of dreams is that they don’t surprise or shock or alienate the person who’s dreaming – the dreamer, on the contrary, feels that their dream is inevitable. “The mind of the man who dreams,” Breton writes, “is fully satisfied by what happens to him. The agonizing question of possibility is no longer pertinent. Kill, fly faster, love to your heart’s content… Let yourself be carried along, events will not tolerate your interference. You are nameless. The ease of everything is priceless.”

Most physiologists and psychologists of the early 20th century would have agreed with him, right up until his last sentence. While the surrealists looked to dreams to reveal a mind beyond conciousness, scientists of the day considered them insignificant, because you can’t experiment on a dreamer, and you can’t repeat a dream.

Since then, others have joined the battle over the meaning – or lack of meaning – of our dreams. In 1977, Harvard psychiatrists John Allan Hobson and Robert McCarley proposed “random activation theory” ‘activation-synthesis theory’, in a rebuff to the psychoanalysts and their claim that dreams had meanings only accessible via (surprise, surprise) psychonalysis. Less an explanation, more an expression of exasperation, their theory held that certain parts of our brains concoct crazy fictions out of the random neural firings of the sleeping pons (a part of the brainstem).

It is not a bad theory. It might go some way to explaining the kind of hypnagogic imagery we experience when we doze, and that so delighted the surrealists. It might even bring us closer to actually reconstructing our dreams. For instance, we can capture the brain activity of a sleeper, using functional magnetic resonance imaging, hand that data to artificial intelligence software that’s been trained on about a million images, and the system will take a stab at what the dreamer is seeing in their dream. The Japanese neuroscientist Yukiyasu Kamitani made quite a name for himself when he tried this in 2012.

Six years later, at the Serpentine Gallery in London, artist Pierre Huyghe integrated some of this material into his show UUmwelt — and what an astonishing show it was, its wall screens full of bottles becoming elephants becoming screaming pigs becoming geese, skyscrapers, mixer taps, dogs, moles, bat’s wings…

But modelling an idea doesn’t make it true. Activation-synthesis theory has inspired some fantastic art, but it fails to explain one of the most important physiological characteristics of dreaming – the fact that dreams paralyse the dreamer.

***

Brains have an alarming tendency to treat dreams as absolutely real and to respond appropriately — to jump and punch when the dream says jump! and punch! Dreams, for the dreamer, can be very dangerous indeed.

The simplest evolutionary way to mitigate the risk of injury would have been to stop the dreamer from dreaming. Instead, we evolved a complex mechanism to paralyse ourselves while in the throes of our night-time adventures. 520 million years of brain evolution say that dreams are important and need protecting.

This, rather than the actual content of dreams, has driven research into the sleeping brain. We know now that dreaming involves many more brain areas, including the parietal lobes (involved in the representation of space) and the frontal lobes (responsible for decision-making, problem-solving, self-control, attention, speech production, language comprehension – oh, and working memory). Mice dream. Dogs dream. Platypuses, beluga whales and ostriches dream; so do penguins, chameleons, iguanas and cuttlefish.[

We’re not sure about turtles. Octopuses? Marine biologist David Scheel caught his snoozing pet octopus Heidi on camera, and through careful interpretation of her dramatic colour-shifts he came to the ingenious conclusion that she was enjoying an imaginary crab supper. The clip, from PBS’s 2019 documentary Octopus: Making Contact is on YouTube.

Heidi’s brain structure is nothing like our own. Still, we’re both dreamers. Studies of wildly different sleeping brains throw up startling convergences. Dreaming is just something that brains of all sorts have to do.

We’ve recently learned why.

The first clues emerged from sleep deprivation studies conducted in the late 1960s. Both Allan Rechtschaffen and William Dement showed that sleep deprivation leads to memory deficits in rodents. A generation later, and researchers including the Brazilian neuroscientist Sidarta Ribeiro were spending the 1990s unpicking the genetic basis of memory function. Ribiero himself found the first molecular evidence of Freud’s “day residue” hypothesis, which has it that the content of our dreams is often influenced by the events, thoughts, and feelings we experience during the day.

Ribeiro had his own fairly shocking first-hand experience of the utility of dreaming. In February 1995 he arrived in New York to start at doctorate at Rockefeller University. Shortly after arriving, he woke up unable to speak English. He fell in and out of a narcoleptic trance, and then, in April, woke refreshed and energised and able to speak English better than ever before. His work can’t absolutely confirm that his dreams saved him, but he and other researchers have most certainly established the link between dreams and memory. To cut a long story very short indeed: dreams are what memories get up to when there’s no waking self to arrange them.

Well, conscious thought alone is not fast enough or reliable enough to keep us safe in the blooming, buzzing confusion of the world. We also need fast, intuitive responses to critical situations, and we rehearse these responses, continually, when we dream. Collect dream narratives from around the world, and you will quickly discover (as literary scholar Jonathan Gottschall points out in his 2012 book The Storytelling Animal) that the commonest dreams have everything to do with life and death and have very little time for anything else. You’re being chased. You’re being attacked. You’re falling. You’re drowning. You’re lost, trapped, naked, hurt…

When lives were socially simple and threats immediate, the relevance of dreams was not just apparent; it was impelling. And let’s face it: a stopped clock is right at least twice a day. Living in a relatively simple social structure, afforded only a limited palette of dream materials to draw from, was it really so surprising that (according to the historian Suetonius) Rome’s first emperor Augustus found his rise to power predicted by dreams?

Even now, Malaysia’s indigenous Orang Asli people believe that by sharing their dreams, they are passing on healing communications from their ancestors. Recently the British artist Adam Chodzko used their practice as the foundation for a now web-based project called Dreamshare Seer, which uses generative AI to visualise and animate people’s descriptions of their dreams. (Predictably, his AI outputs are rather Dali-like.)

But humanity’s mission to interpret dreams has been eroded by a revolution in our style of living. Our great-grandparents could remember a world without artificial light. Now we play on our phones until bedtime, then get up early, already focused on a day that is, when push comes to shove, more or less identical to yesterday. We neither plan our days before we sleep, nor do we interrogate our dreams when we wake. Is it any wonder, then, that our dreams are no longer able to inspire us?

Growing social complexity enriches our dream lives, but it also fragments them. Last night I dreamt of selecting desserts from a wedding buffet; later I cuddled a white chicken while negotiating for a plumbing contract. Dreams evolved to help us negotiate the big stuff. Having conquered the big stuff (humans have been apex predators for around 2 million years), it is possible that we have evolved past the point where dreaming is useful, but not past the point where dreaming is dangerous.

Here’s a film you won’t have seen. Petrov’s Flu, directed by Kirill Serebrennikov, was due for limited UK release in 2022, even as Vladimir Putin’s forces were bumbling towards Kiev.

The film opens on our hero Petrov (Semyon Serzin), riding a trolleybus home across a snowbound Yekaterinburg. He overhears a fellow passenger muttering to a neighbour that the rich in this town all deserve to be shot.

Seconds later the bus stops, Petrov is pulled off the bus and a rifle is pressed into his hands. Street executions follow, shocking him out of his febrile doze…

And Petrov’s back on the bus again.

Whatever the director’s intentions were here, I reckon this is a document for our times. You see, Andre Breton wrote his manifesto in the wreckage of a world that had turned its machine tools into weapons, the better to slaughter itself — and did all this under the flag of the Enlightenment and reason.

Today we’re manufacturing new kinds of machine tools, to serve a world that’s much more psychologically adept. Our digital devices, for example, exploit our capacity for focused attention (all too well, in many cases).

So what of those devices that exist to make our sleeping lives better, sounder, and more enjoyable?

SleepScore Labs is using electroencephalography data to analyse the content of dreams. BrainCo has a headband interface that influences dreams through auditory and visual cues. Researchers at MIT have used a sleep-tracking glove called Dormio to much the same end. iWinks’s headband increases the likelihood of lucid dreaming.

It’s hard to imagine light installations, ambient music and scented pillows ever being turned against us. Then again, we remember the world the Surrealists grew up in, laid waste by a war that had turned its ploughshares into swords. Is it so very outlandish to suggest that tomorrow, we will be weaponising our dreams?