People are by far the easiest animals to train. Whenever you try to get some bit of technology to work better, you can be sure that you are also training yourself. Steadily, day by day, we are changing our behaviours to better fit with the limitations of our digital environment. Whole books have been written about this, but we keep making the same mistakes. On 6 November 2014, at Human Interactive, a day-long conference on human-machine interaction at Goldsmith’s College in London, Rodolphe Gelin, the research director of robot-makers Aldebaran, screened a video starring Nao, the company’s charming educational robot. It took a while before someone in the audience (not me) spotted the film’s obvious flaw: how come the mother is sweating away in the kitchen while the robot is enjoying quality time with her child?

We still obsess over the “labour-saving” capacities of our machines, still hanker after more always-elusive “free time”, but we never think to rethink the value of labour itself. This is the risk we run: that we will save ourselves from the very labour that makes our lives worthwhile.

Organised by William Latham and Frederic Fol Leymarie, Human Interactive was calculated (quite deliberately, I expect) to stir unease.

Beyond the jolly, anecdotal presentations about the computer games industry from Creative Assembly’s Guy Davidson and game designer Jed Ashforth, there emerged a rather unflattering vision of how humans best interact with machines. The biophysicist Michael Sternberg, for instance, is harnessing the wisdom of crowds to gamify and thereby solve difficult problems in systems biology and bioinformatics. For Sternberg’s purposes, people are effectively interchangeable components in a kind of meat parallel-processing system. Individually, we do have some merit: we are good at recognising and classifying patterns. Thisat least makes us better than pigeons, but only at the things that pigeons are good at already.

Sternberg would be mortified to see his work described in such terms – but this is the point: human projects, fed through the digital mill, emerge with their humanity stripped away. It’s up to people at the receiving end of the milling process to put the humanity back in. I wasn’t sure, listening to Nilli Lavie’s presentation on attention, to what human benefit her studies would be put. The UCL neuroscientist’s key point is well taken – that people perform best when they are neither overloaded with information, nor deprived of sufficient stimulus. But what did she mean by her claim that wandering attention loses the US economy around two billion dollars a year? Were American minds to be perfectly focused, all the year round, would that usher in some sort of actuarial New Jerusalem? Or would it merely extinguish all American dreaming? Without a space for minds to wander in, where would a new idea – any new idea – actually come from?

Not that ideas will save us. Ideas, in fact, got us into this mess in the first place, by reminding us that the world as-is is less than it could be. We are very good at dreaming up scenarios that we are not currently experiencing. We are all too capable of imagining elusive “perfect” experiences. Digital media feed these yearnings. There is something magical about a balanced spreadsheet, a glitchless virtual surface, the beauty of a symmetrical avatar under perfect, unreal light.

Henrietta Bowden-Jones, founder and director of the National Problem Gambling Clinic, is painfully aware of how digital media encourage our obessive and addictive behaviours. Games are hardly the new tobacco — at least, not yet — but psychologists are being hired to make them ever-more addictive; Bowden-Jones’s impressively understated presentation suggested that games may soon generate behavioral and social problems as acute as those thrown up by on-line gambling.

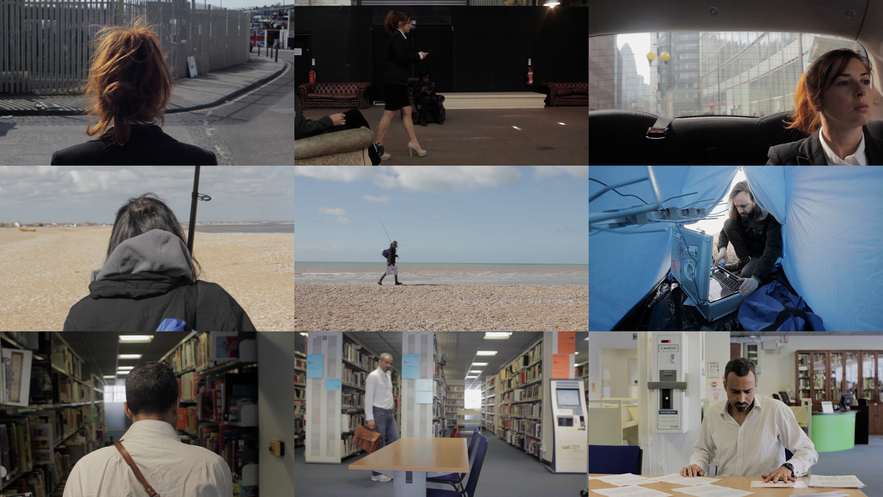

The day after the conference, Goldsmith’s College hosted Creative Machine, a week-long exhibition of machine creativity. In a church abutting the campus, robots sketched human skulls, balanced pendulums, and noodled around with evolutionary algorithms.I expected still more alienation, a surfeit of anxiety. In fact, Creative Machine left me feeling strangely reassured.

Those of us who play with computers, or know a little about science, harbour what amounts to a religious conviction: that that somewhere deep down, at the bottom of this messy reality, there is an order at work. Call it mathematics, or physics, or reason. Whichever way you cut it, we believe there’s a law. But this just isn’t true. Put a computer to work in the real world, and it messes up. More exciting still, it messes up in just the ways we would. Félix Luque Sánchez’s simple robots on rails shuttle backwards and forwards in a brave and ultimately futile attempt to balance a pendulum. Anyone who’s ever tried to balance a book on their head will recognise themselves in every move, every acceleration, every hesitation – every failure.

Even a robot who knows what it’s doing will get entangled. Patrick Tresset has programmed a robot called Paul with the rules of life drawing and draughtsmanship. Paul, presented with a still-life, follows these rules unthinkingly – and yet every picture it churns out is unique, shaped by tiny, unrepeatable fluctations in its environment (a snaggy biro, a heavy-footed passer-by, a cloud crossing the sun…).

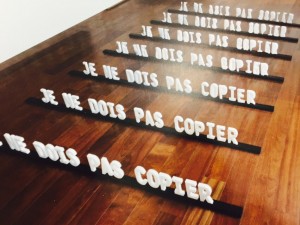

If an emblem were needed for this show, then Cécile Babiole provides it. She has run the phrase “NE DOIS PAS COPIER” (literally: “one shouldn’t copy”) through a 3-D copier, over and over again, playing a familiar game of generational loss. And it’s the strangest thing: as they decay, her printed plastic letters take on organic form, become weeds, become coral, become limbs and organs. They lose their original meaning, only to acquire others. They do not become nothing, the way an over-photocopied picture becomes nothing. They become rich and strange.

Maths, rationality and science are magnificent tools with which to investigate the world. But we commit a massive and dangerous category error when we assume the world is built out of maths and reason.

With a conference to beat us, and an exhibition to entice us, Latham and Fol Leymarie have led us, without us ever really noticing, to a view of new kind of digital future. A future of approximations and mistakes and acts of bricolage. It is not a human future, particularly. But it is a future that accommodates us, and we should probably be grateful.