Reading Serhii Plokhy’s Atoms and Ashes for the Telegraph, 8 May 2022

Jimmy Carter is the only US president to have had hands-on experience of nuclear reactors. As part of the US Navy’s nuclear submarine program, he once helped disassemble a Canadian research reactor that had gone into meltdown. His enthusiasm for the technology was, to say the least, measured: “US dependence on nuclear power should be kept to the minimum necessary to meet our needs,” he told the UN General Assembly in 1976, tying the fortunes of the industry ever more tightly to immediate geopolitical demands.

But the nuclear industry has never been able to respond to such demands quickly enough. Right now, Germany is finding this out the hard way. The country decommissioned its nuclear fleet after the 2011 Fukushima accident. Ill-suited to renewables, beset by winter doldrums and long overcasts, it bet on being able to import its energy. Now it finds itself in a hopeless tangle, under pressure to stop importing Russian gas, yet unable to reverse its nuclear decommissioning programme.

It’s this unwieldiness, this inflexibility that puts nuclear power, time and again, on the wrong side of history, and powers the deeper arguments running under Serhii Plohki’s terrifying compendium of notorious nuclear mishaps.

The ostensible theme of Atoms and Ashes is straightforward: what happens when nuclear power generation goes wrong?

Rejecting the distinction between military and civil nuclear programmes (the uranium 235 and plutonium used in nuclear munitions are, after all, usually obtained from civil reactors), Plohky begins in the Marshall islands in March 1954 where, according to a notorious White House briefing, “the wind failed to follow the predictions,” spreading fallout from a US thermonuclear test across Rongelap and other inhabited islands.

In the UK, around 12 kilogrammes of uranium escaped through the stacks of the Windscale piles between 1954 and 1957, giving maybe 300 people terminal cancer.

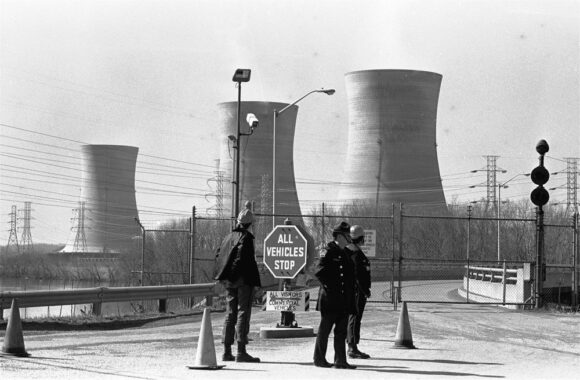

In 1979 a nuclear core melted down inside a reactor on Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania. No uncontrolled release of radiation ever occurred.

There’s a pattern here, and let’s not be bashful: the West won. Compare these chapters with the ones about the nuclear waste fires at Kyshtym in the Urals in 1957 (nadir of an environmental catastrophe so severe, some of the 20,000 square miles contaminated were turned into a nature park to keep people out) and the explosion at Chernobyl in Soviet Ukraine in 1986 (which killed over thirty outright and over the years has likely seeded 4000 people with terminal cancer). These accounts spell out exactly what to expect when you deny vital information to people and then bully them into performing impossible miracles on shoddy equipment. If civil nuclear power were a theatre of the Cold War (and it was) then the West, with its capitalistic working practices, won hands down.

But complacency is not an option. The peaceful application of nuclear power was the industry’s grail in those dark years, but “atoms for peace” far from ending want and war, have merely encouraged nuclear proliferation. (India produced its first plutonium in a reactor supplied by Canada, calling its first nuclear test a “peaceful nuclear explosion”.)

Not can we comfortably assume that, like the oil industry, like the hydo-electric industry, nuclear power is evolving and improving and becoming safer year on year.

True, the oil industry kills 264 times as many people as the nuclear industry, to produce just over seven times the amount of useful energy. True, nuclear power produces barely three fifths the amount of carbon that solar energy does, and generates four times as much power.

But the build quality of nuclear reactors across the globe is probably going down, not up, as reactor design loses research funding in the developed world, while relatively primitive reactors, further “simplified” to cut costs, are sold to unstable states hungry for nuclear prestige.

Plohki’s last major chapter analyses the multiple reactor meltdown at Fukushima in 2011. The earthquake which hit on Friday 11 March — an 8.9 on the Richter scale — shook the entire planet on its axis and jolted the whole of Japan several feet sideways. The tsunami that followed was far more terrible than the Fukushima Daiichi designers had allowed for. Yet no one died from acute radiation poisoning, and while cancer deaths cannot be ruled out, studies have as yet found no increase in the rate of such deaths.

Reasons for the deep unease that swept the globe following the Fukushima accident will be found neither in the figures, nor in the historical circumstances. (The worst that happened politically was that the prime minster, Naoto Kan, was roundly pilloried for grandstanding on Japanese TV.)

No, what really got under everyone’s skin were the eight painfully long days of pure terror during which the Fukushima disaster unfolded, with its various equipment failures, meltdowns, and releases of radioactive materials.

Look at it this way: were some poor sod to lose control of his muscle car on a cattle grid near Penistone, we would merely shrug and sigh. But imagine if the act of wrapping that car around a tree took over a week, and each excruciating moment of it were broadcast live on television. What would our reactions be then? Come Monday, how many of us would leave our cars in the garage?

On the outside, Atoms and Ashes looks like an altogether unnecessary contribution to the “Say something should happen” argument against nuclear power. But Plohki’s gripping, measured accounts of human error and staggering heroism in the face of the slow, unwieldy and terrifying forces of nuclear power get under the skin of problem.

We’ve developed a clean, safe energy generation system. But never mind the materials it uses, the machine itself scares the living daylights out of us: slow, inexorable, mysterious, and persistent (no nuclear power station has ever been fully decommissioned).

Nuclear power is safe, and clean, and a nightmare — and one cannot simply reason one’s way out of a nightmare.