Imbeciles: The Supreme Court, American eugenics, and the sterilization of Carrie Buck by Adam Cohen (Penguin Press)

Defectives in the Land: Disability and immigration in the age of eugenics by Douglas C. Baynton (University of Chicago Press)

for New Scientist, 22 March 2016

ONE of 19th-century England’s last independent “gentleman scientists”, Francis Galton was the proud inventor of underwater reading glasses, an egg-timer-based speedometer for cyclists, and a self-tipping top hat. He was also an early advocate of eugenics, and his Hereditary Genius was published two years after the first part of Karl Marx’s Das Kapital.

Both books are about the betterment of the human race: Marx supposed environment was everything; Galton assumed the same for heredity. “If a twentieth part of the cost and pains were spent in measures for the improvement of the human race that is spent on the improvement of the breed of horses and cattle,” he wrote, “what a galaxy of genius might we not create! We might introduce prophets and high priests of civilisation into the world, as surely as we… propagate idiots by mating cretins.”

What would such a human breeding programme look like? Would it use education to promote couplings that produced genetically healthy offspring? Or would it discourage or prevent pairings that would otherwise spread disease or dysfunction? And would it work by persuasion or by compulsion?

The study of what was then called degeneracy fell to a New York social reformer, Richard Louis Dugdale. During an 1874 inspection of a jail in New York State, Dugdale learned that six of the prisoners there were related. He traced the Jukes family tree back six generations, and found that some 350 people related to this family by blood or marriage were criminals, prostitutes or destitute.

Dugdale concluded that, like genius, “degeneracy” runs in families, but his response was measured. “The licentious parent makes an example which greatly aids in fixing habits of debauchery in the child. The correction,” he wrote, “is change of the environment… Where the environment changes in youth, the characteristics of heredity may be measurably altered.”

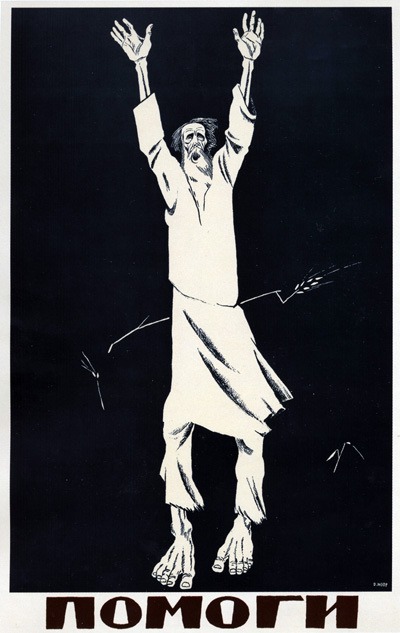

Other reformers were not so circumspect. An Indiana reformatory promptly launched a eugenic sterilisation effort, and in 1907 Indiana enacted the world’s first compulsory sterilisation statute. California followed suit in 1909. Between 1927 and 1979, Virginia forcibly sterilised at least 7450 “unfit” people. One of them was Carrie Buck, a woman labelled feeble-minded and kept ignorant of the details of her own case right up to the point in October 1927 when her fallopian tubes were tied and cauterised using carbolic acid and alcohol.

In Imbeciles, Adam Cohen follows Carrie Buck through the US court system, past the desks of one legal celebrity after the other, and not one of them, not Howard Taft, not Louis Brandeis, not Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr, gave a damn about her.

Cohen anatomises in pitiless detail how inept civil society can be at assimilating scientific ideas. He also does a good job explaining why attempts to manipulate the genetic make-up of whole populations can only fail to improve the genetic health of our species. Eugenics fails because it looks for genetic solutions to what are essentially cultural problems. The anarchist biologist Peter Kropotkin made this point as far back as 1912. Who were unfit, he asked the first international eugenics congress in London: workers or monied idlers? Those who produced degenerates in slums or those who produced degenerates in palaces? Culture casts a huge influence over the way we live our lives, hopelessly complicating our measures of strength, fitness and success.

Readers of Cohen’s book would also do well to watch out for Douglas Baynton’s Defectives in the Land, to be published in June. Focusing on immigrant experiences in New York, Baynton explains how ideas about genetics, disability, race, family life and employment worked together to exclude an extraordinarily diverse range of men and women from the shores of the US.

“Doesn’t this squashy sentimentality of a big minority of our people about human life make you puke?” Holmes once exclaimed. Holmes was a miserable bigot, but he wasn’t wrong to thirst for more rigour in our public discourse. History is not kind to bad ideas.