I reviewed this mix of prescience, philosophy and irony for New Scientist’s Culture Lab.

Here’s a more relaxed version for Lem initiates:

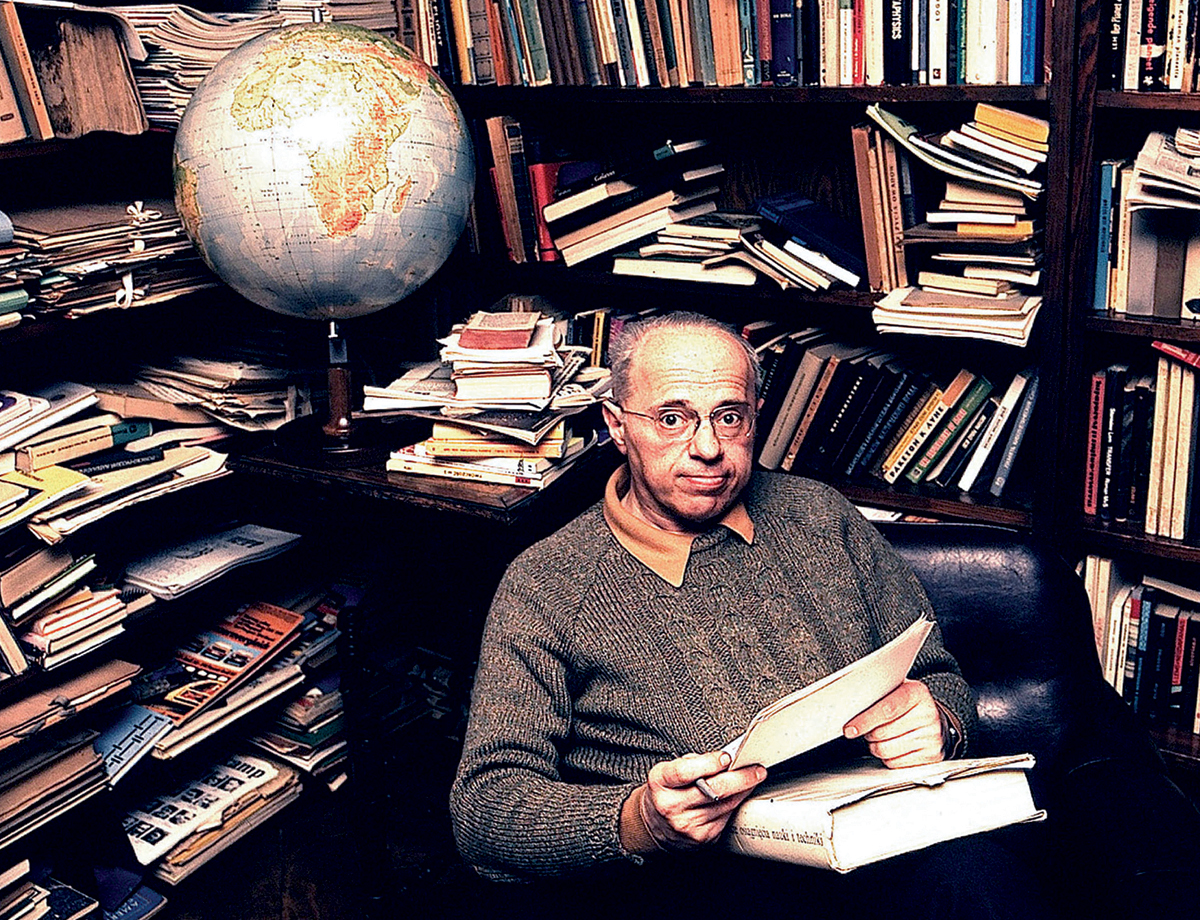

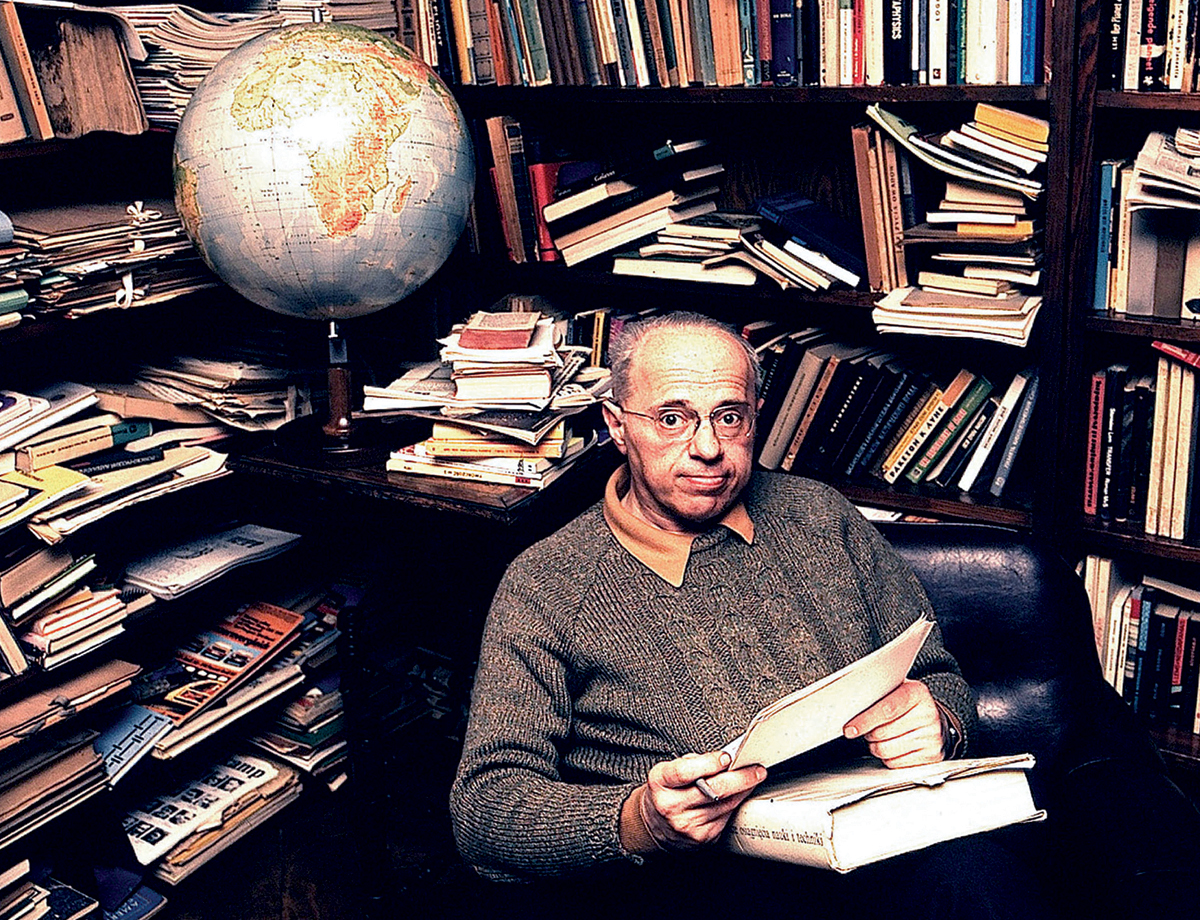

Image shamelessly ripped from Aleksander Jalosinski http://aleksanderjalosinski.pl

Halfway through his epic cybernetic rewiring of the Western cultural project, at the top of his rhetorical curve, and scant pages before the neologisms begin to gum and tack, tripping the reader’s feet (the second half is a slog), Polish satirist Stanislaw Lem recasts the entire universe as a boarding house inhabited by Mr Smith, a bank clerk, his puritanical aunt, and a female lodger.

The boarding house has a glass wall, and all the greats of science are about to look through that wall and draw truths about the universe from what they observe. Ptolemy notes how, when the aunt goes down to the cellar to fetch some vegetables, Mr Smith kisses the lodger. He develops a purely descriptive theory, “thanks to which one can know in advance which position will be taken by the two upper bodies when the loqwer one finds itself in the lowest position.”

Newton enters. “He declares that the bodies’ behaviour depends on their mutual attraction.”

So it goes on. Heisenberg notices some indeterminacy in their behaviour: “For instance, in the state of kissing, Mr Smith’s arms do not always occupy the same position.”

And on. And on. Mathematics comes unstuck in the ensuing complexity, where “a neural equivalent of an act of sneezing would be a volume whose cover would have to be lifted with a crane.”

Science is steadily pushing us into a Goethian cul-de-sac in which, the more accurate our theory, the closer it comes to the phenomenon itself, in all its ambiguity, strangeness, and inexplicability. At this point, Lem says, analysis must be abandoned in favour of creative activity — “imitological practice.” as he would have it, “considering the phenomenon itself its most perfect representation.”

There are nested ironies here, and it’s the devil’s work to unpick them all. Then again, any reader of Lem will have guessed this from the off, and will relish the opportunity afforded by this English translation – incredibly, for a book written in 1964 by a literary celebrity and reasonably well translated elsewhere, the first in the English language. Summa’s translator is Joanna Zylinska, a professor of new media and communications at Goldsmiths. Her work is diligent, imaginative, painstakingly precise; sometimes one wishes, in the later chapters, that she would be a little more slapdash and cut to the chase a little more, but this is Lem’s fault, not hers.

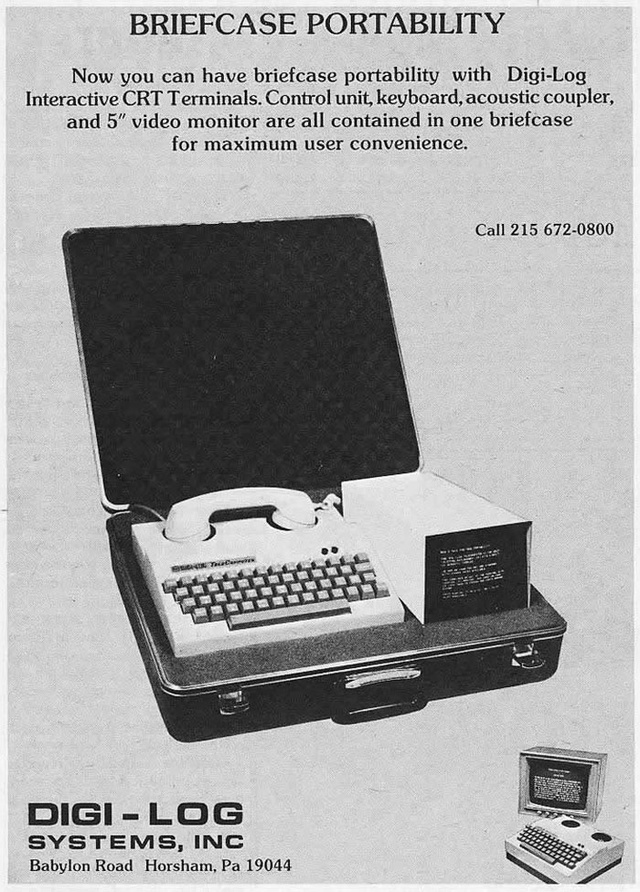

Lem was a garrulous old sod who said Steven Soderbergh’s 2002 version of his novel Solaris should have been renamed “Love in Outer Space” and put up a sign outside his house warning of “ferocious dogs” (in truth, five friendly dachshunds). Though he had some important intellectual training, Lem ploughed his own furrow, conjuring with ideas that would not become common currency for another half-century: (virtual reality, nanotechnology, artificial intelligence, technological singularity…) When he succumbs to the autodidact’s anxiety, his prose is not pretty.

But then, Lem always worked at the edge of aesthetic possibility — which is to say, he was a science fiction writer. Science fiction is notorious for biting the hand that feeds it, for deliberately running counter to all expectation, and getting lost for decades at a time in the contested, often ugly territory where the humanities leave off and the sciences begin. Science fiction prides itself on crashing and burning, again and again, against the walls of narrative expectation and good taste. It’s the Gully Foyle of literature, fearsome and deranged and perilous in its promise: a Prometheus figure shoving fire in your face. “Catch this!”

This is what the Summa throws up: a vision of intelligence as cul-de-sac. Intelligence carries conscious beings to a point where their theories are no longer useful to them, where their hard-won objectivity drowns in a glut of complexity, and the only way to forward is for them to grow into the fabric of the world.

Fermi’s paradox: “If we are alive and intelligent and making some noise, where, in all the cosmos, is everybody else?”

Lem’s answer: Look at the rocks. Intelligence is a stepping stone on a circular path back to brute is-ness.

So much for cosmic irony; there’s a local, political irony here too, which needs some more exploration.

You see, after the Soviet occupation of Eastern Poland, Lem was banned from Polytechnic study owing to his “bourgeois origin”. His father pulled strings to get him accepted on a course in medicine at Lwów University in 1940, but this brought him up against the quack theories of Stalin’s intellectual poster-boy, the agronomist Trofim Denisovich Lysenko. Lem satirized Lysenko in a science magazine and soon abandoned his medical studies.

A word about Lysenko. With the blood of millions already on his hands from collectivisation – not to mention the wholesale eradication of countless varieties of domesticated plant – Josef Stalin needed to feed what was left of his nation. He wanted food and he wanted it now. Enter Trofim Denisovich, peddling an idea of evolution already two centuries out of date. Lysenko said things change their form in response to the environment, and pass any changes directly to their offspring. No element of chance. No randomness in selection. No genetic code to learn. Giraffes have long necks because their parents stretch.

And there is no brake on this process, neither, according to Lysenko. No natural conservatism. Things want to change. They just need some kindly direction. Spin your wheel and stick in your thumbs: the living world is clay. Oats will turn to wild oats, pines to firs, sunflowers to zinnias. Animal cells will turn into plant cells. Plants into animals! Cells from soup! “How can there be hereditary diseases in a socialist society?” From the nonliving will come the living.

Fast forward twenty years, and we have the Summa, and the Summa says,

“We cannot therefore catalogue Nature, our finitude being one of the reasons for this. Yet we can turn Nature’s infinity against it, so to speak by working, as Technologists…”

And what, exactly, will this work look like? (Bear in mind here that Lysenko cited the brilliant fruit-tree specialist Ivan Michurin as his intellectual forebear):

“A scientist wants an algorithm, wheras the technologist is more like a gardener who plants a tree, picks apples, and is not bothered about “how the tree did it.” A scientist considers such a narrow, utiliterian and pragmatic approach a sin against the laws of Full Knowledge. It seems that those attitudes will change in the future.”

The Summa is not just Lem’s vision of the future; it is Lysenko’s.

Of course this (irony of ironies) doesn’t mean that the vision is merely mischevious, a bitter political joke (though I think it is that). Perhaps Lem thinks Lysenko was simply ahead of his time, reaching for a plasticity in nature that it will take another century of biological research to effect.

Predictably, from a writer who seems permanently dangling off the edge of everyone else’s intellectual curve, Lem’s minatory vision is being explored and independently invented in the oddest places. Never mind the blandishments of the Kurzweilians and the extropians: Lem calls them “homunculists”, an inspired expression of contempt. What about Ridley Scott’s movie Prometheus? What about that animate yet unliving black goo that can bring life to sterile planets, in all its savagery, appetite and guile? What about that unsmiling species of near-Gods who, having mastered birth (the sexism is deliberate and important), sets life at its own neck in the service of some unnamed Next Project? Lem would have hated it. But then, Lem was an inveterate ironist who describes the Summa itself, that most cherished project, as a “slightly modernised… version of the famous Ars Magna, which clever Lullus presented quite a long time ago, that is, the the year 1300, and which was rightly mocked by Swift in Gulliver’s Travels.”

It is not that the ironies get in the way. It’s that the world itself is ironical, and Lem, with his vision-of-the-future-that-is-no-future, is its John the Baptist. Even as you follow him, watch him rip out the signposts. Even as you beg for water, watch him defecate in each and every roadside well. Gawp in dismay as he assembles Potemkin villages on the barren skyline only to kick them into the dust. Then: walk on. (It’s not like you have any choice.) The path looks straight. You know it’s anything but. You know, God help you, that you will come by this place again.