Taking a look at the artwork around COP21, the Paris climate talks, for New Scientist, 11 December 2015.

In the failing winter light, in full view of Paris’s Cité des Sciences et de L’Industrie, the dead are rising from the Canal de l’Ourcq. Municipal bicycles; shopping trolleys; a filing cabinet. Volunteers have hauled up these unedifying objects and the artist has mounted them just above the water’s surface.

The point, probably, is that in our ever more crowded, ever more connected world, there is no longer any “away” in which to throw anything; we must live with our waste, as surely as we must live with our past. Something like that. In any event Breaking the Surface by Michael Pinsky is, well, recycled: it has been done before (indeed, dates back to the work of artist Marcel Duchamp around 1913-15), and it makes a point that is an unwinning combination of the necessary and the overdone, like a parent always telling you to eat your greens.

I came to Paris to cover what was billed as an unprecedented cultural ferment around COP21, the UN conference on climate change. I expected more than a few mud-encrusted chairs and bikes.

But as the hours went by, and the days, and the kilometres, two painful truths become evident. First, there will be no ferment. The most exciting public events have been cancelled, scaled back, or hurriedly relocated. The recent terror attacks on Paris have seen to that, and the subsequent city-wide ban on demonstrations, not to mention the controversial decision to place local climate activists under house arrest.

Even more painful is the realisation that our current cultural responses to the wicked problem of climate change look as narrow, as blinkered, and as hard to communicate as the scientific ones. Climate change is no longer a purely scientific problem: it is a political and social truth we must handle as best we can. And we aren’t handling it. We can’t handle it. We haven’t got a clue.

So why is there so little in the cultural bank? On the face of it, art and culture have enough of the right kind of lenses to focus on the wicked problem’s wickedness and to prompt new thoughts, forge new understandings and settlements – maybe even spur new actions.

However, in the absence of any fresh currency, the organisers of ArtCOP21 – the cultural programme surrounding the talks, and running on well after any deal is brokered – had a duty to see what could be done with art-culture’s existing toolkit.

Take visualisation, making the invisible visible. Like Breaking the Surface, this is a very old game. But in the right hands it can work well, and arguably, one of the best pieces in Paris is EXIT at the Palais de Tokyo, a full and quite scary updating of an immersive video installation first shown in 2008.

In a dark room, an Earth 2 metres across moves remorselessly around a 360-degree screen. A sound like the chattering of millions accompanies six animated maps as they move round the screen, with their all too respectable data showing how the connection between humans and their environment has fallen off a cliff over the past seven years.

The titles speak volumes: Population Shifts: Cities; Remittances: Sending Money Home; Political Refugees and Forced Migration; Natural Catastrophes; Rising Seas, Sinking Cities; Speechless and Deforestation.

The pixels making up each map represent human experiences, some dots standing in for thousands of people on the move: does attachment to a place now have more to do with moving across it than living on it?

The man who inspired the work, philosopher Paul Virilio, captured its spirit in a separate film: “It’s almost as though the sky, and the clouds in it and the pollution of it, were making their entry into history.”

EXIT is a chilling but effective call to action by design studio Diller Scofidio + Renfro, along with Mark Hansen, Laura Kurgan, Ben Rubin and a host of others, exposing connections that would otherwise have been missed.

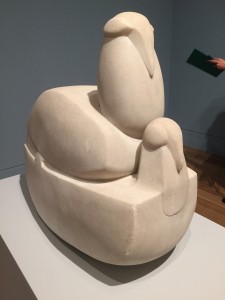

At the other end of the empathy spectrum is the deceptive work of Janet Laurence and Tania Kovats. On the face of things, both artists appear to be concerned more with aesthetic values rather than social and political ones. But in fact their exquisite, precise work is all about raw, tranformative emotion, the stuff that generates change without knowing how it does so.

Laurence’s Deep Breathing (Resuscitation for the Reef) at the Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle looks glacial and cool, with glass containers showing pieces of broken coral, shells and the skeletons of marine animals.

But the glass is meant to represent a resuscitation unit for the Great Barrier Reef, full of bleached-out dead and dying creatures – including some units that suggest babies in intensive care.

For environmental artist Laurence, the reef is not a tourist object but all about fragility: it invokes our need to heal it, to pity it, to love it. Emotion. What a great gig!

And for Tania Kovats, too. Evaporation is one of ArtCOP21’s highlighted works outside Paris: it premiered during the Manchester Science Festival in October and will show until March next year at Manchester’s Museum of Science and Industry.

As the recipient of a Lovelock Art Commission, which invites an artist to take inspiration from the work of independent scientist James Lovelock, her emotion is for water, for the planet’s seas as barometer of planetary health, for Gaia theory.

Kovats’s installation comprises three large, shallow, metal bowls made from the shapes of the world’s three major oceans: Atlantic, Pacific and Indian. A solution of salt and blue ink placed in each bowl gradually evaporates during the show, leaving crusts of salt crystals in concentric rings.

It is never the same again. It bears witness to the metaphorical movement of oceans, unlike the poem Dear Matafele Peinem, which is forced to bear witness to the real movement of water.

Waves of the future

Marshall Islander Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner first performed her poem at the 2014 UN climate meeting in New York. And she read it again – to a flash mob during a “cultural takeover” of London’s St Pancras International Station the day the conference opened.

The promises to her Buddha-fat baby that her generation would not let the waves of the future literally roll over the Marshall Islands should have been embarrassing:

And they’re marching for you, baby

they’re marching for us

because we deserve to do more than just

survive

we deserve

to thrive…

so just close those eyes, baby

and sleep in peace

because we won’t let you down

you’ll see.

but they are more than that, they are terrible. Because no one can make such promises.

You can dream up perfectly legitimate ways to fix the world. Indeed, you jolly well should. The now pudgy little toddler Matafele won’t thank us for not trying. Ultimately, while scientists measure problems, and technologists can build tools to deal with them, what we do and when and how is a political issue. It is up to us.

Alternatiba, the global village of alternatives, was one of those grass-roots, left-leaning outings that are very easy to satirise (there were a lot of polar bear suits about, a lot of singing) but not, ultimately, so very easy to dismiss.

“Change the system, not the climate”, was the festival’s motto, the point being that our entire global civilisation is built on fossil fuels, and we’re unlikely to be able to wean ourselves off them without asking a lot of hard questions about our society.

The problem for Alterniba was that it brought together a whole set of perfectly reasonable local practices, from organic gardening to straw-bale house construction, and – in a paroxysm of magical thinking – posited them as global solutions.

“Think global, act local” is one of those phrases whose euphony masks its fatuity. No local solution is globally applicable. The trick is surely for everyone to act local and think local: not to tilt at “the system” willy-nilly, but – in the teeth of serious political and legislative opposition – to operate outside it.

Outside or inside the system, is it worthwhile to simply play with climate change? Tomás Saraceno thinks so. An artist obsessed with weightlessness, the sky and the possibilities offered by floating utopias, Saraceno is spearheading a global effort to resettle humanity in the atmosphere inside habitable solar balloons. Or something.

Uncertainties around the scale of project, its aims and the degree of seriousness we should assign to it, are part of Saraceno’s game. He is an artist, after all: questions and speculations are his stock in trade. In launching a handful of balloons made out of plastic bags, Saraceno raises some very good questions: about who owns what in the environment; where our individual physical freedom comes from, and who grants it; about risk, and responsibility, and civics, and community.

His Aerocene movement achieves what Alterniba cannot: it extricates itself from the global agenda set by global agencies and pursues (or at any rate dreams up) a blank canvas – the air itself! – for its tiny, winning experiments in featherweight living. Revolutions have sprung from less.

And in a world that has very little space and patience for revolutions, Saraceno’s chutzpah – and in the proper sense of the word, his naiveté – are much to be commended.