At what point does a practical problem become an existential one? When do we have to admit that not everyone can experience everything – and what do we do about that? Forgery is no solution because good forgeries are, by definition, as exclusive as originals: if the original turns up, the forgery loses all value. But what if we undermined cultural norms to the point where fakery was the norm?

A visit to the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam and the Tinguely Museum Basel for New Scientist, 13 May 2017.

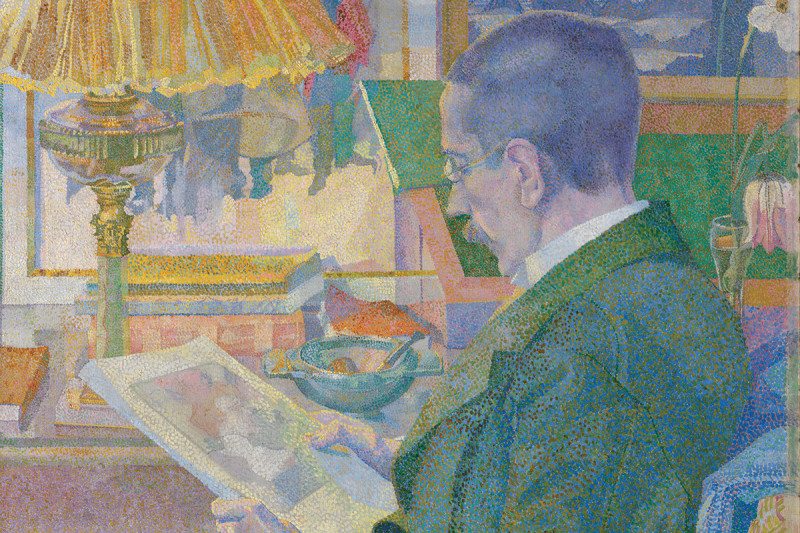

IMPRESSIONISM, the movement that shaped a generation of European artists, was concerned above all with light, colour and the mechanics of visual perception. Only one of its leading lights concerned himself, without apology, to the business of fame – Vincent van Gogh. He got what was coming to him: absolutely nothing. Dealers failed to sell a single canvas in his lifetime.

Tastes change. On 2 June 1973, in a park behind the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, a museum dedicated to van Gogh’s work opened to an ever-swelling crowd of admirers. In 2014, 1.6 million people visited. Last year it was 2.1 million – 20 times the number the museum was designed to accommodate – all there to see just 250 paintings and 700 drawings and letters.

At what point does a practical problem become an existential one? When do we have to admit that not everyone can experience everything – and what do we do about that? Forgery is no solution because good forgeries are, by definition, as exclusive as originals: if the original turns up, the forgery loses all value.

What if we undermined cultural norms to the point where fakery was the norm? This is the state of affairs dreamed up by Polish writer Stanislaw Lem in his 1976 novel The Futurological Congress, which features this diary entry: “Spent a few free hours… in the city. Could hardly control my horror as I looked at all the displays of wealth… An art gallery in Manhattan practically giving away original Rembrandts and Matisses… The fiendishness is that part of this mass deception is open and voluntary, letting people think they can draw the line between fiction and fact. And since no one any longer responds to things spontaneously – you take drugs to study, drugs to love, drugs to rise up in revolt, drugs to forget – the distinction between manipulated and natural feelings has ceased to exist.”

Doubtless the curators at the Van Gogh Museum have no such nefarious plans. But, faced with those queues, they are resorting to technology, even virtual reality.

Their most innocent-looking intervention is a dedicated location-based app by Marjolein Fennis that will entertain those waiting to enter, turning potentially fractious hordes into ad hoc communities of gamers.

In an effort to avoid delays and bottlenecks, museum designers scrape eye-tracking studies and video footage for insights. Some 85 per cent of the museum’s visitors are tourists, which means they get up late and roll up to the museum at the same time, 11 am.

A computer program developed with Erasmus University in Rotterdam uses algorithms more usually found in stock market trackers to predict visitor behaviour. Thus armed, the museum has come up with incentives to reduce peak time visits by around 60 per cent, even while visitor numbers have increased by nearly half.

“We don’t want as many visitors as possible, we want each visitor to have the best experience as possible,” says Milou Halbesma, the Van Gogh Museum’s director of public affairs.

Amsterdam, also badly bottlenecked, is planning to adopt similar technology later this year to get tourists out of the city and into the rest of the country.

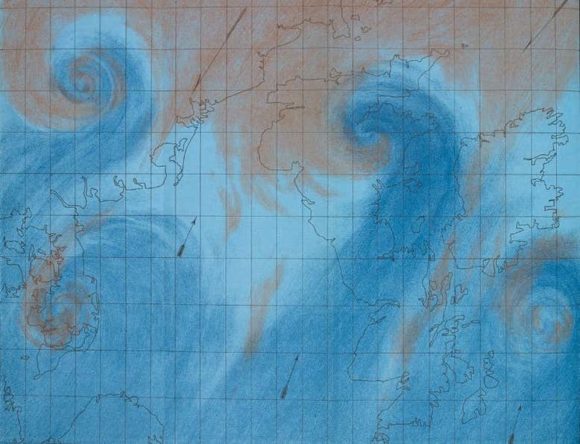

Technology can also satisfy demand, especially in Asia, by bringing van Gogh’s art to the people. To this end, the museum has produced a digitally enhanced immersive experience, Meet Vincent van Gogh. It sounds hokey: visitors can wander with Vincent from rural Netherlands to the streets of Paris, pull up a seat at The Potato Eaters‘ table, and step into a life-sized Yellow House. In reality, the exhibition stimulates genuine interest, without leaving the visitor feeling cheated that they haven’t been in contact with the real work.

The museum’s limited run of Relievo reproductions take the opposite tack. Based on 3D scans of the paintings, including cracks in the paint and traces of paint layers, these surreally accurate reproductions took the museum and Fujifilm Belgium seven years to achieve. If you ever wanted to run your hand down the thick, impasto brushstrokes of van Gogh’s Sunflowers, now is your chance. This approach was also targeted at the overseas market, especially Hong Kong. A Dubai hotel exhibited them in 2015.

The only downside is that these strategies increase the number of people who want to see van Gogh’s real work. An exhibition currently at the Van Gogh Museum, Prints in Paris 1900, explores another very successful way of dealing with the sheer popularity of art and the celebrity of individual artists.

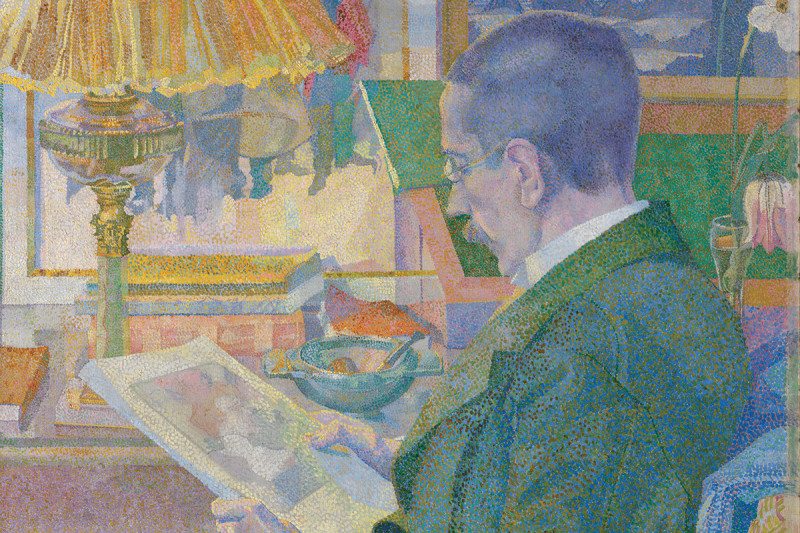

The fad for prints at the end of the 19th century not only decorated the hoardings and walls of Paris with colourful public art in the form of adverts, it also let everyone with a half-decent salary own an “original”. No two prints were identical – the imprimatur of the artist was visible and even, depending on the inks used, tangible. And the private nature of collections meant darker, more intimate themes could be explored by artist and collector.

Producing art ordinary people could own was a cultural as well as a technological breakthrough. But there is a snag, felt more sharply now than at the time these prints were produced. The low lighting at the Prints show reveals the vulnerability of works on paper. Unless these pieces are endlessly reproduced, dissolving their connection with the artist, they will have to spend almost all their life in storage, out of the public gaze.

The original is the gallery-goer’s holy grail. When Mark Rothko’s badly faded murals, painted for a Harvard University dining room, were rehung in 2014, an expensive lighting system was used to restore their colour. Over-painting them would have been an act of sacrilege. No one thinks this way about buildings. St John’s Cathedral, in the Dutch city of ‘s-Hertogenbosch, for example, had whole pinnacles reinstalled and some statues recarved from scratch. This process began in the 19th century, using easily weathered limestone, which means some of the most recently reinstalled figures are actually copies of copies.

Gallery-goers are less forgiving. “I think it should always be very clear for the audience what you are looking at,” says Halbesma. “That is why we shall never show copies in our museum – because this is the moment when you meet Vincent and his work.”

“Unless artworks on paper are endlessly reproduced, they spend their life in storage, out of public gaze”

And the posters and prints upstairs? “They are all originals,” Halbesma says. “But we have big problems because of the light and their vulnerability. A lot of museums are already working with facsimile.” The implication is clear: catch this while you can.

Perhaps we should leave it to artists to determine what role provenance plays in their work. Van Gogh, desperate for that elusive sale, embraced the idea of reproduction. A letter to his brother Theo in December 1882 reads: “What I wrote to you in my last letter about a plan for making prints for the people is something to which I hope you’ll give some thought one day. I don’t have a fixed plan about this myself as yet… But I don’t doubt the possibility of doing something like this, nor its usefulness.”

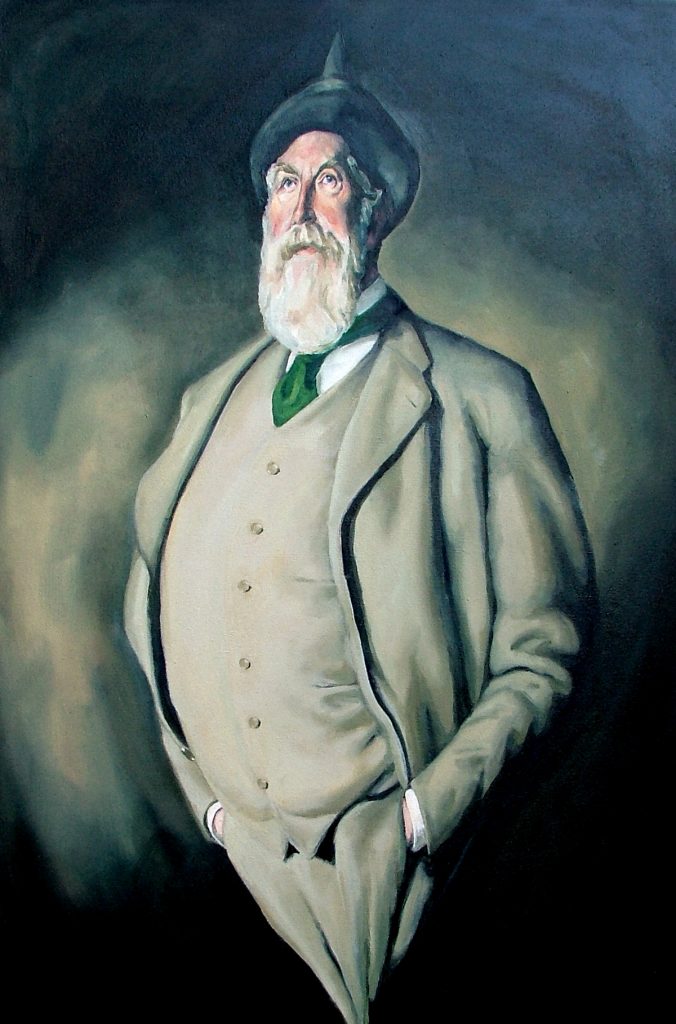

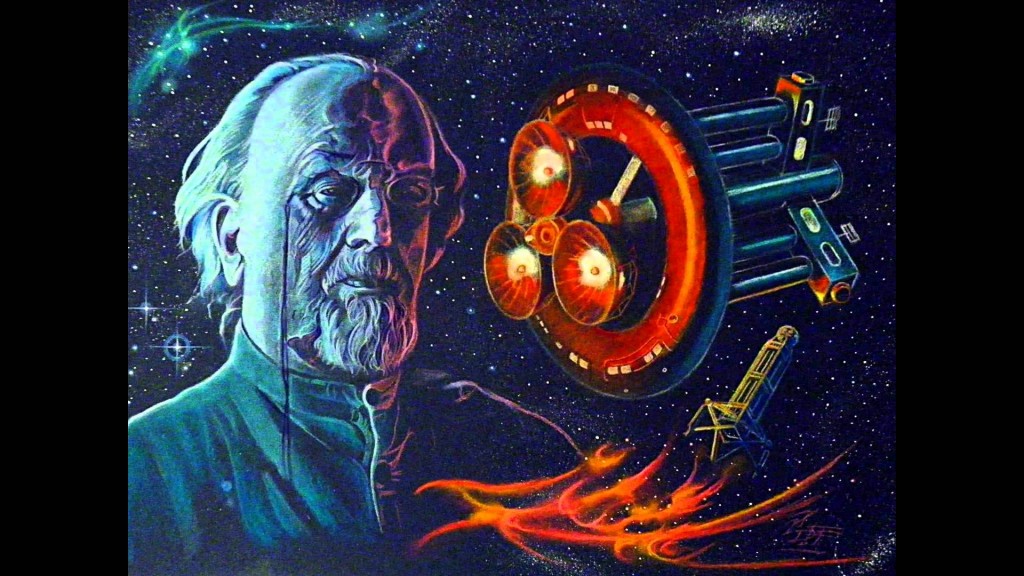

The nearby Stedelijk Museum’s recent show of kinetic sculpture by 20th-century Swiss artist, showman and mischief-maker Jean Tinguely shows a rather different attitude. Tinguely was no ordinary mechanic, and some of his work, such as Homage to New York, was designed to burst apart in showers of sparks. His less self-destructive work is hardly more stable; the Stedelijk show had 42 moving pieces, rigged to timers to eke out the fun between the inevitable repairs.

It reminded me of a story told by Midas Dekkers in his book The Way of All Flesh – and an important part of the story of provenance. The Stedelijk once had a piece of Tinguely’s called Gismo. Tinguely insisted it should run constantly so the noise would lead people to it from wherever they were. A curator took him at his word, and for a brief, happy while, everyone got to see Gismo.

That’s the trouble with art: if you want it to live, you may have to let it die.