Reading Forecast by Joe Shute for the Telegraph, 28 June 2021

As a child, journalist Joe Shute came upon four Ladybird nature books from the early 1960s called What to Look For. They described “a world in perfect balance: weather, wildlife and people all living harmoniously as the seasons progress.”

Today, he writes, “the crisply defined seasons of my Ladybird series, neatly quartered like an apple, are these days a mush.”

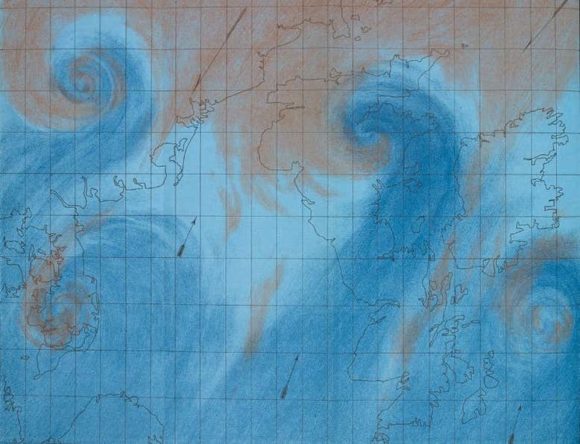

Forecast is a book about phenology: the study of lifecycles, and how they are affected by season, location and other factors. Unlike behemothic “climate science”, phenology doesn’t issue big data sets or barnstorming visualisations. Its subject cannot be so easily metricised. How life responds to changes in the seasons, and changes in those changes, and changes in the rates of those changes, is a multidimensional study whose richness would be entirely lost if abstracted. Instead, phenology depends on countless parochial diaries describing changes on small patches of land.

Shute, who for more than a decade has used his own diary to fuel the “Weather Watch” column in the Daily Telegraph, can look back and see “where the weather is doing strange things and nature veering spectacularly off course.” Watching his garden coming prematurely to life in late winter, Shute is left “with a slightly sickly sensation… I started to sense not a seasonal cycle, but a spiral.” (130)

Take Shute’s diary together with countless others and tabulate the findings, and you will find that all life has started shifting northwards — insects at a rate of five metres a day, some dragonflies at between 17 and 28 metres a day.

How to write about this great migration? Immediately following several affecting and quite horrifying eye-witness scenes from the global refugee crisis, Shute writes: “The same climate crisis that is rendering swathes of the earth increasingly inhospitable and driving so many young people to their deaths, is causing a similar decline in migratory bird populations.”

I’m being unkind to make a point (in context the passage isn’t nearly so wince-making), but Shute’s not the first to discover it’s impossible to speak across all scales of the climate crisis at once.

Amitav Ghosh’s 2016 The Great Derangement is canonical here. Ghosh explained in painful detail why the traditional novel can’t handle global warming. Here, Shute seems to be proving the same point for non-fiction — or at least, for non-fiction of the meditative sort.

Why doesn’t Shute reach for abstractions? Why doesn’t he reach for climate science, and for the latest IPCC report? Why doesn’t he bloviate?

No, Shute’s made of sterner stuff: he would rather go down with his corracle, stitching together a planet on fire (11 wildfires raging in the Arctic circle in July 2018), human catastrophe, bird armageddon, his and his partner’s fertility problems, and the snore of a sleeping dormouse, across just 250 pages.

And the result? Forecast is a triumph of the most unnerving sort. By the end it’s clearly not Shute’s book that’s coming unstuck: it’s us. Shute begins his book asking “what happens to centuries of folklore, identity and memory when the very thing they subsist on is changing, perhaps for good”, and the answer he arrives at is horrific: folklore, identity and memory just vanish. There is no reverse gear to this thing.

I was delighted (if that is quite the word) to see Shute nailing the creeping unease I’ve felt every morning since 2014. That was the year the Met Office decided to give storms code-names. The reduction of our once rich, allusive weather vocabulary to “weather bombs” and “thunder snow”, as though weather events were best captured in “the sort of martial language usually preserved for the defence of the realm” is Shute’s most telling measure of how much, in this emergency, we have lost of ourselves.