How the Zebra Got its Stripes and Other Darwinian Just So Stories by Léo Grasset

The Serengeti Rules: The quest to discover how life works and why it matters by Sean B. Carroll

Lysenko’s Ghost: Epigenetics and Russia by Loren Graham

The Great Derangement: Climate change and the unthinkable by Amitav Ghosh

reviewed for New Scientist, 15 October 2016

JUST how much does the world follow laws? The human mind, it seems, may not be the ideal toolkit with which to craft an answer. To understand the world at all, we have to predict likely events and so we have a lot invested in spotting rules, even when they are not really there.

Such demands have also shaped more specialised parts of culture. The history of the sciences is one of constant struggle between the accumulation of observations and their abstraction into natural laws. The temptation (especially for physicists) is to assume these laws are real: a bedrock underpinning the messy, observable world. Life scientists, on the other hand, can afford no such assumption. Their field is constantly on the move, a plaything of time and historical contingency. If there is a lawfulness to living things, few plants and animals seem to be aware of it.

Consider, for example, the charming “just so” stories in French biologist and YouTuber Léo Grasset’s book of short essays, How the Zebra Got its Stripes. Now and again Grasset finds order and coherence in the natural world. His cost-benefit analysis of how animal communities make decisions, contrasting “autocracy” and “democracy”, is a fine example of lawfulness in action.

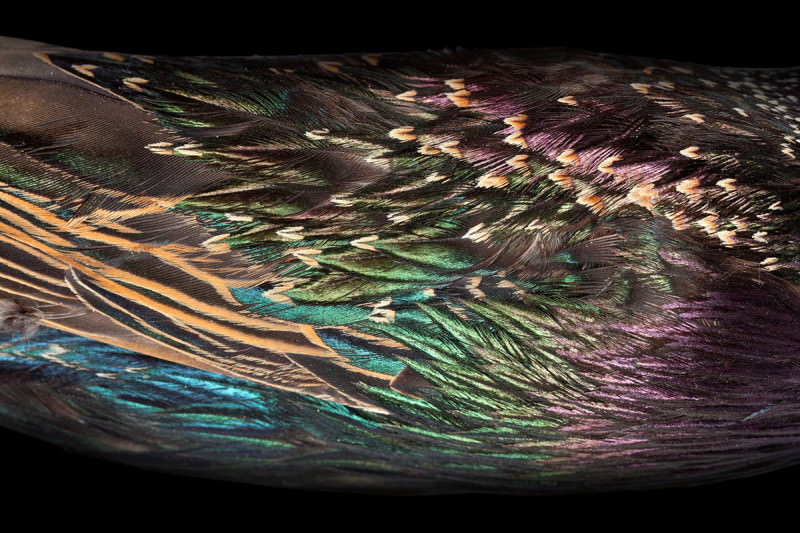

But Grasset is also sharply aware of those points where the cause-and-effect logic of scientific description cannot show the whole picture. There are, for instance, four really good ways of explaining how the zebra got its stripes, and those stripes arose probably for all those reasons, along with a couple of dozen others whose mechanisms are lost to evolutionary history.

And Grasset has even more fun describing the occasions when, frankly, nature goes nuts. Take the female hyena, for example, which has to give birth through a “pseudo-penis”. As a result, 15 per cent of mothers die after their first labour and 60 per cent of cubs die at birth. If this were a “just so” story, it would be a decidedly off-colour one.

The tussle between observation and abstraction in biology has a fascinating, fraught and sometimes violent history. In Europe at the birth of the 20th century, biology was still a descriptive science. Life presented, German molecular biologist Gunther Stent observed, “a near infinitude of particulars which have to be sorted out case by case”. Purely descriptive approaches had exhausted their usefulness and new, experimental approaches were developed: genetics, cytology, protozoology, hydrobiology, endocrinology, experimental embryology – even animal psychology. And with the elucidation of underlying biological process came the illusion of control.

In 1917, even as Vladimir Lenin was preparing to seize power in Russia, the botanist Nikolai Vavilov was lecturing to his class at the Saratov Agricultural Institute, outlining the task before them as “the planned and rational utilisation of the plant resources of the terrestrial globe”.

Predicting that the young science of genetics would give the next generation the ability “to sculpt organic forms at will”, Vavilov asserted that “biological synthesis is becoming as much a reality as chemical”.

The consequences of this kind of boosterism are laid bare in Lysenko’s Ghost by the veteran historian of Soviet science Loren Graham. He reminds us what happened when the tentatively defined scientific “laws” of plant physiology were wielded as policy instruments by a desperate and resource-strapped government.

Within the Soviet Union, dogmatic views on agrobiology led to disastrous agricultural reforms, and no amount of modern, politically motivated revisionism (the especial target of Graham’s book) can make those efforts seem more rational, or their aftermath less catastrophic.

In modern times, thankfully, a naive belief in nature’s lawfulness, reflected in lazy and increasingly outmoded expressions such as “the balance of nature”, is giving way to a more nuanced, self-aware, even tragic view of the living world. The Serengeti Rules, Sean B. Carroll’s otherwise triumphant account of how physiology and ecology turned out to share some of the same mathematics, does not shy away from the fact that the “rules” he talks about are really just arguments from analogy.

“If there is a lawfulness to living things, few plants and animals seem to be aware of it”

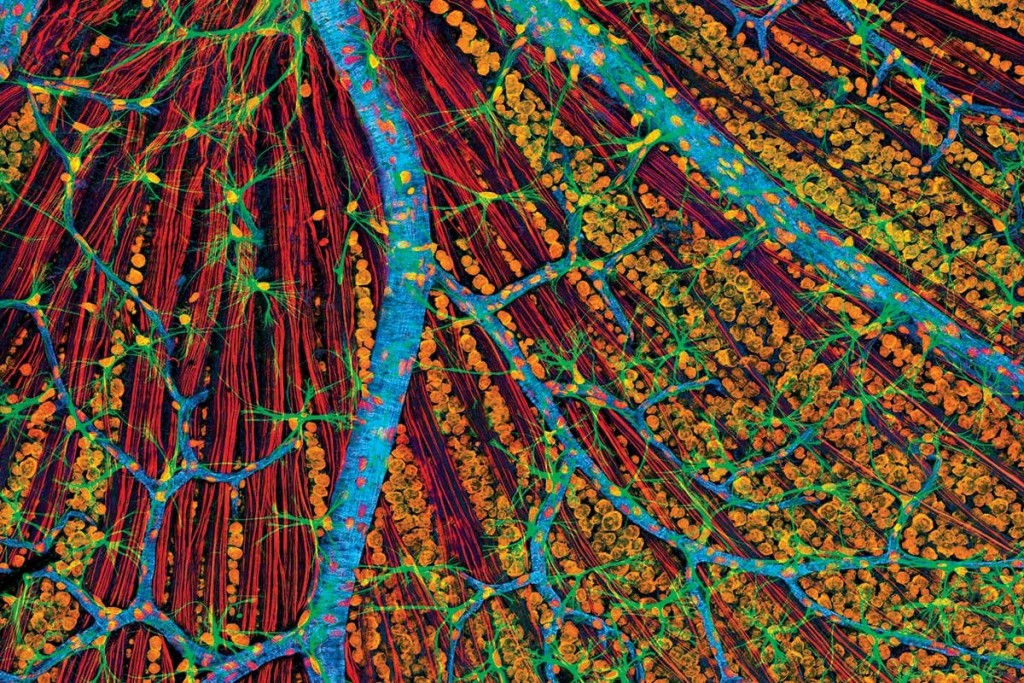

Some notable conservation triumphs have led from the discovery that “just as there are molecular rules that regulate the numbers of different kinds of molecules and cells in the body, there are ecological rules that regulate the numbers and kinds of animals and plants in a given place”.

For example, in Gorongosa National Park, Mozambique, in 2000, there were fewer than 1000 elephants, hippos, wildebeest, waterbuck, zebras, eland, buffalo, hartebeest and sable antelopes combined. Today, with the reintroduction of key predators, there are almost 40,000 animals, including 535 elephants and 436 hippos. And several of the populations are increasing by more than 20 per cent a year.

But Carroll is understandably flummoxed when it comes to explaining how those rules might apply to us. “How can we possibly hope that 7 billion people, in more than 190 countries, rich and poor, with so many different political and religious beliefs, might begin to act in ways for the long-term good of everyone?” he asks. How indeed: humans’ capacity for cultural transmission renders every Serengeti rule moot, along with the Serengeti itself – and a “law of nature” that does not include its dominant species is not really a law at all.

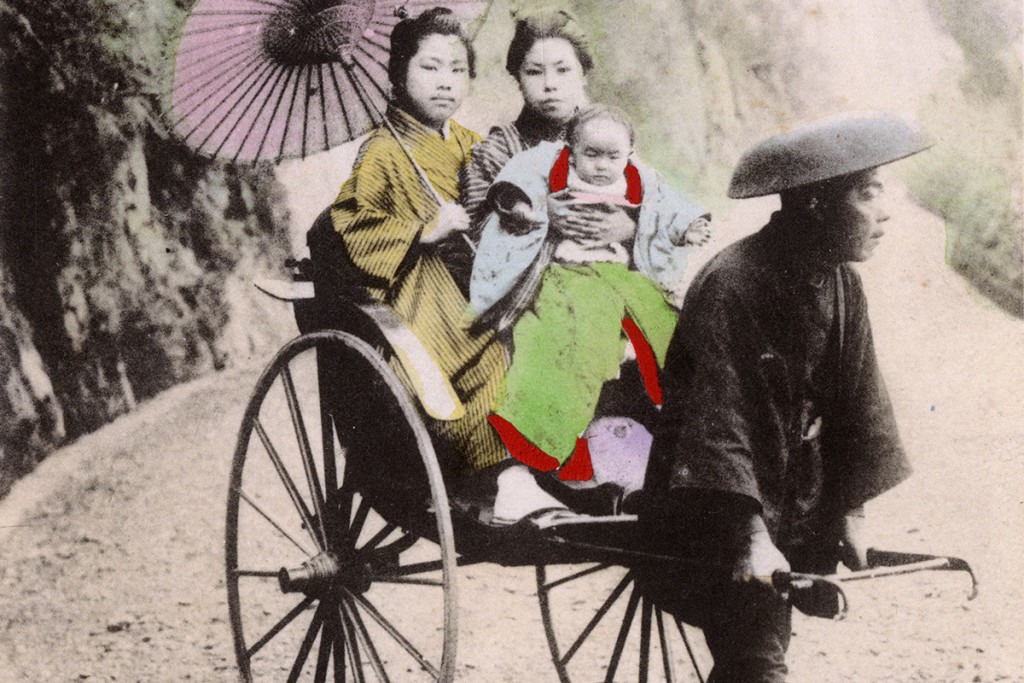

Of course, it is not just the sciences that have laws: the humanities and the arts do too. In The Great Derangement, a book that began as four lectures presented at the University of Chicago last year, the novelist Amitav Ghosh considers the laws of his own practice. The vast majority of novels, he explains, are realistic. In other words, the novel arose to reflect the kind of regularised life that gave you time to read novels – a regularity achieved through the availability of reliable, cheap energy: first, coal and steam, and later, oil.

No wonder, then, that “in the literary imagination climate change was somehow akin to extraterrestrials or interplanetary travel”. Ghosh is keenly aware of and impressively well informed about climate change: in 1978, he was nearly killed in an unprecedentedly ferocious tornado that ripped through northern Delhi, leaving 30 dead and 700 injured. Yet he has never been able to work this story into his “realist” fiction. His hands are tied: he is trapped in “the grid of literary forms and conventions that came to shape the narrative imagination in precisely that period when the accumulation of carbon in the atmosphere was rewriting the destiny of the Earth”.

The exciting and frightening thing about Ghosh’s argument is how he traces the novel’s narrow compass back to popular and influential scientific ideas – ideas that championed uniform and gradual processes over cataclysms and catastrophes.

One big complaint about science – that it kills wonder – is the same criticism Ghosh levels at the novel: that it bequeaths us “a world of few surprises, fewer adventures, and no miracles at all”. Lawfulness in biology is rather like realism in fiction: it is a convention so useful that we forget that it is a convention.

But, if anthropogenic climate change and the gathering sixth mass extinction event have taught us anything, it is that the world is wilder than the laws we are used to would predict. Indeed, if the world really were in a novel – or even in a book of popular science – no one would believe it.