THE SCIENCE FICTION FUTURE

With a keynote by multi-award winning science-fiction writer ALASTAIR REYNOLDS, this packed afternoon of short films and discussions explores how science fiction is guiding us towards an uncertain tomorrow.

Saturday May 30

12.30–6pm

Blue Room, mezzanine level

BFI Southbank, Belvedere Road

London SE1 8XT

A free drop-in event

(Help us keep track of numbers by registering at Eventbrite)

12.30 Screenings

Building and testing a Paul-III drawing robot

Patrick Tresset, 2014 (1’ 30)

Patrick Tresset is a French artist who uses robotics to create cybernetic representations of the artist. His robots incorporate research findings from computer vision, artificial intelligence and cognitive computing. @patricktresset

The Willful Marionette

Lilla LoCurto & Bill Outcault, 2014 (2’ 46)

Created during a residency with the University of North Carolina, Charlotte, the marionette is 3D-printed from the scanned image of a human figure and responds in real time to spontaneous human gestures. Their intention was not to create a perfectly functioning robot, but to imbue an obviously mechanical marionette with the ability to solicit a physical and emotional dialogue.

Strandbeest (compilation)

Theo Jansen, 2014 (3’ 55)

In 1990 the Dutch artist Theo Jansen began building large self-actuating mechanisms out of PVC. He strives to equip his creations with their own artificial intelligence so they can avoid obstacles, such as the sea itself, by changing course. @StrandBeests

The Afronauts

Cristina De Middel, 2013 (4’ 30)

In 1964, still living the dream of their recently gained independence, Zambia started a space program that would put the first African on the moon. The project was founded and led by Edward Makuka, a school teacher. The United Nations declined their support. Photojournalist Cristina De Middel assembled surviving documents from the project and integrated them with her own imagery. @lademiddel

The Moon (Luna, excerpt)

Pavel Klushantsev, 1965 (2’ 00)

Concluding scenes from a visionary documentary describing how the moon will be developed, from the first lunar mission to the construction of lunar cities and laboratories.

Reactvertising™ R&D

John St., 2014 (0’ 56)

John Street is a Canadian creative agency. @thetweetsofjohn

13:00 Introduction

Simon Ings

@simonings

13:10 Keynote: “On the Steel Breeze”

Alastair Reynolds

@aquilarift

Marrying human concerns to monstrously scaled backdrops, Alastair Reynolds is one of our finest writers of science fiction. He spent twelve years within the European Space Agency, designing and building the S-Cam, the world’s most advanced optical camera, before returning to his native Wales in 2008. His most recent novel, appearing in September 2013, is On the Steel Breeze, a sequel to Blue Remembered Earth.

13.30 Screenings

The Centrifuge Brain Project

Till Nowak, 2012 (6’ 35) Many thanks to ShortFilmAgency Hamburg,

A portrait of the science behind seven experimental fun park rides. Humans are constantly looking for bigger, better, faster solutions to satisfy their desires, but they never arrive at a limit – it’s an endless search. @TillNowak

SEFT–1 Abandoned Railways Exploration Probe

Ivan Puig and Andrés Padilla Domene, 2014 (3’ 05)

Puig and Domene (Los Ferronautas) built their striking silver road-rail vehicle to explore the abandoned passenger railways of Mexico and Ecuador, an iconic infrastructure now lying in ruins, much of it abandoned due to the privatisation of the railway system in 1995, when many passenger trains were withdrawn, lines cut off and communities isolated. The artists’ journeys, captured in videos, photographs and collected objects, establish a notion of modern ruins.

Growth Assembly

Daisy Ginsberg & Sacha Pohflepp, 2009 (3’ 33)

A collection, illustrated by Sion Ap Tomos, of seven plants that have been genetically engineered to grow objects. Once assembled, parts from the seven plants form a herbicide sprayer – an essential commodity used to protect these delicate, engineered horticultural machines from an older, more established nature. @alexandradaisy | @plugimi

Hair Highway

Juriaan Booij, 2014 (4’ 28)

A contemporary take on the ancient Silk Road. As the world’s population continues to increase, human hair has been re-imagined as an abundant and renewable material, with China its biggest exporter. Studio Swine explores how the booming production of hair extensions can be expanded beyond the beauty industry to make desirable, Shanghai-deco style products. @StudioSwine

Magnetic Movie

Semiconductor, 2007 (4’ 47)

Artists Ruth Jarman & Joe Gerhardt (Semiconductor) reveal the secret lives of magnetic fields around NASA’s Space Sciences Laboratories, UC Berkeley, to recordings of space scientists describing their discoveries. Are we observing a series of scientific experiments, or a documentary of a fictional world? @Semiconducting

14:00 Panel: “Unreliable evidence”

Museums and galleries are using mocked-up objects, films and documents to entertain, baffle and provoke us — but what happens when we can no longer tell the difference between them and the real thing?

Alec Steadman, formerly of The Hut Project, joined the arts-science hub The Arts Catalyst as Curator in April 2015.

A curator, producer and artists’ agent, Robert Devcic uses objects to challenge, inform and deepen our ideas of the real world. Through his gallery GV Art, he pioneers work that erases the boundary between art and science, fact and fiction.

Cher Potter is a senior editor at the fashion forecasting company WGSN. She analyses social, political and cultural trends and their potential impact on the fashion industry. She is part of the curatorial team for a forthcoming exhibition at the V&A Museum titled The Future: A History.

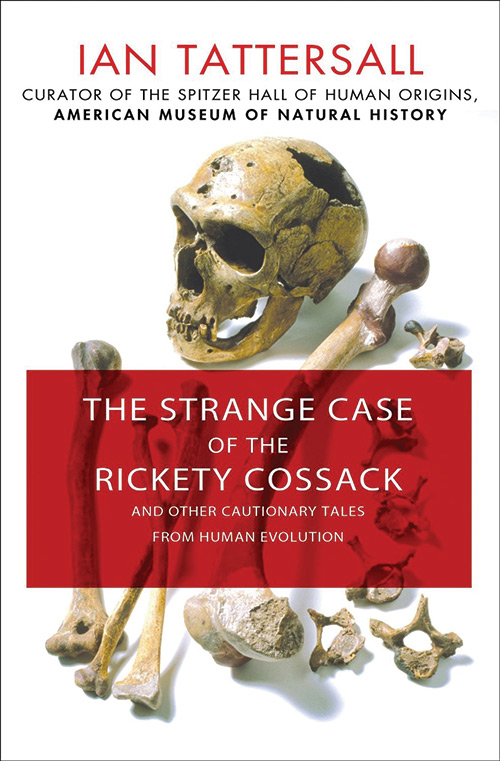

Deputy keeper of technologies and engineering at the Science Museum, Doug Millard has just completed work on a major exhibition of Russian space exploration to be staged at the Science Museum in September 2015.

@TheArtsCatalyst | @GV_Art

Lost in Fathoms

Anaïs Tondeur & Jean-Marc Chomaz, 2014 (3′ 27)

14:45 screenings

Big Dog Overview

Boston Dynamics, 2010 (3’ 24)

BigDog is a rough-terrain robot that walks, runs, climbs and carries heavy loads. BigDog’s four legs are articulated like an animal’s, with compliant elements to absorb shock and recycle energy from one step to the next. @BostonDynamics

Farmer’s Pet

Joshua Allen Harris, 2008 (2’ 17)

US street artist Joshua Allen Harris uses ordinary black garbage and shopping bags to make his pieces, tying them down to subway grates with tape in the hope the strong gusts from the trains will be strong enough to inflate his characters and animate them. @tweetsbyjosh

Shrink (performance at Brucknerhaus, Linz, Austria)

Lawrence Malstaf, 2009 (4’ 25)

Belgian artist Lawrence Malstaf develops installation and performance art dealing with space and orientation. His projects frequently involve advanced technology and the participation of visitors.

Big Dog Beta: – early Big Dog quadruped robot testing (excerpt)

Seedwell, 2011 (0’ 48)

The somewhat flawed predecessor to Boston Dynamics’ Big Dog robot. Camera by Dana Kruse. @seedwell

First on the Moon (excerpt)

Aleksei Fedorchenko, 2005 (1’ 30)

Soviet scientists and military authorities managed to launch the first spacecraft 23 years prior to Yuri Gagarin’s flight. Fedorchenko’s first feature tells about everyday life, heroic deeds and tragedy of the first group of the Soviet cosmonauts.

15:00 Panel: “We’re making this up as we go along”

Can we ever ready ourselves for the unexpected? And might the games we play now lead us into making the wrong choices in the future?

Funny and uneasy by turns, Pat Kane’s annual FutureFest festival for the innovation charity NESTA reflected his belief in the importance of play. A musician, writer and political activist, Kane (appearing via Skype) was also one of the founding editors of the Sunday Herald newspaper.

Rob Morgan develops VR titles, including shooters, thrillers and action/comedies, for major game studios, charities, publishers and indies. He was a contributor to the award-winning browser game Samsara and the ARG Unreal City, collaborated with J K Rowling on Pottermore, and has just finished writing the script for the upcoming The Assembly for Morpheus & Oculus Rift.

Andy Franzkowiak has flooded Edinburgh with zombies, sent Siemens’ urban museum The Crystal to 2050, and built the solar system in Deptford. He has previously worked with Punchdrunk, the Southbank Centre and the BBC. Mary Jane Edwards, who develops projects focused on cultural regeneration, social policy and social finance, is his new partner in crime in attempts to blur the distinction between art, education and science.

@theplayethic | @AboutThisLater | @shrinking_space

Afrogalactica: a short history of the future

(performance excerpt)

Kapwani Kiwanga, 2011 (4′ 50)

15:45 screenings

Corner Convenience: “Hoodie”

Near Future Laboratory, 2012, (1’ 40)

Near Future Laboratory’s design-fiction workshop used print and film to explore the future as a place we will, inevitably, take for granted. Its ruling assumption was that the trajectory of all great innovations is to trend towards the counter of your corner convenience store, grocer, 7–11 or petrol station. @nearfuturelab

Reactvertising™

John St., 2014 (3’ 12)

@thetweetsofjohn

New Mumbai

Tobias Revell, 2012 (9’ 17)

During the Indian Civil War the Dharavi slums of Mumbai were flooded with refugees. Sometime later a cache of biological samples appeared through the criminal networks of Mumbai. Revell explains how a refugee community managed to turn these genetically-engineered narcotics into a new type of infrastructure. @tobias_revell

Tender – it’s how people meat

Marcello Gómez Maureira, 2015 (0’ 52)

Tender is the easy way to connect with new and interesting meat around you. @dandymaro

Aurora, the Aura City (excerpt)

Urban IxD, 2013 (3’ 25)

A design fiction created during the Urban IxD summer school in Split, Croatia during August 2013, and led by Tobias Revell and Sara Bozanic. It is 2113. Cities have undergone profound change. A sharing economy holds sway, but the desire for efficiency and optimization has led to the development of highly sophisticated sharing systems that preclude social interaction. The streets have emptied… @tobias_revell | @me_transmedia

Corner Convenience: “Drunk”

Near Future Laboratory, 2012, (1’ 50)

@nearfuturelab

16:00 presentations

Rachel Armstrong creates new materials that possess some of the properties of living systems, and can be manipulated to “grow” architecture. Through extensive collaboration, she builds and develops prototypes of sustainable and self-sustaining metabolic buildings.

@livingarchitect

Lydia Nicholas, is a researcher in collective intelligence at Nesta and founding member of the Future Anthropologies Network. She speaks at conferences about bodies and biology and numbers and making in various combinations. Her favourite bacteria is Paenibacillus vortex.

@LydNicholas

16:15 panel: “This is not a drill”

Rachel Armstrong and Lydia Nicholas join Georgina Voss, Paul Graham Raven and Regina Peldszus to explore how mock-ups, simulations and rehearsals are shaping the real world.

Georgina Voss co-wrote the “Better Made Up” report from NESTA examining the co-influence of science fiction and innovation, and is currently is a resident at Lighthouse Arts, using 3D print technology to promote women’s health in remote regions.

Paul Graham Raven is a postgraduate researcher in infrastructure futures and theory at the University of Sheffield. He is also a science fiction writer, literary critic and essayist.

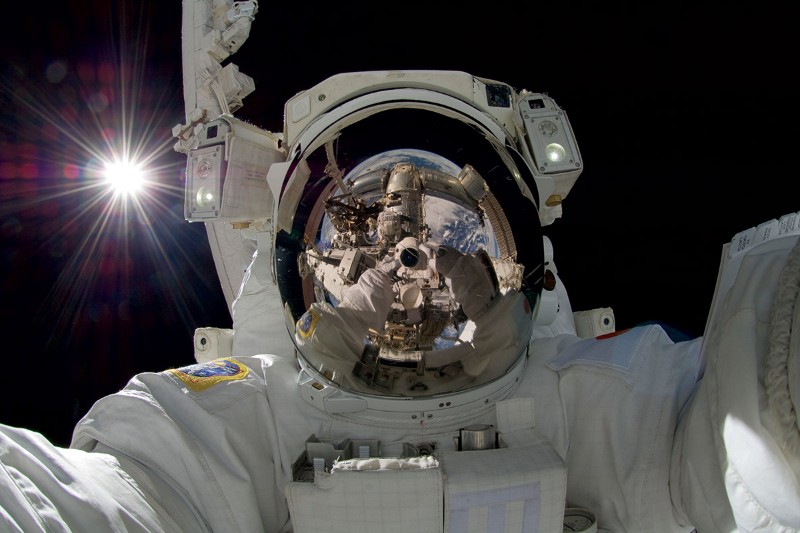

Via Skype, Regina Peldszus explores how humans and technology interact. She was an Internal Research Fellow with the European Space Agency in Darmstadt, Germany. She is now at Leuphana University of Lüneburg, researching the ethics of simulation.

@gsvoss | @PaulGrahamRaven

Forever Future

Sacha Pohflepp, 2010 (4′ 24)

17:00 Screening

Fugitive Futurist: A Q-riosity by “Q”

Gaston Quiribet, 1924 (12’ 00; silent)

An on-the-run inventor claims to have invented a camera which looks into the future, and reveals a grim destiny for London landmarks like Tower Bridge and Trafalgar Square.

17:15 Discussion and screenings

Public Tracks

Hubert Blanz, 2010 (1’ 25)

Excerpt from an audio/video installation. Over the last few years the importance of virtual social networks has greatly increased and has significantly changed the way we communicate.

Brilliant Noise

Semiconductor, 2006 (5’ 50)

After sifting through hundreds of thousands of computer files, made accessible via open access-archives, Semiconductor bring together some of the sun’s finest unseen moments. These images have been kept in their most raw form, revealing the activities of energetic particles. The soundtrack highlights the hidden forces at play upon the solar surface, by directly translating areas of intensity within the image brightness into layers of audio manipulation. @Semiconducting

Singular Occurrence of a Fall

Anaïs Tondeur & Jean-Marc Chomaz, 2014 (1’ 13)

Produced with PhD students during an art and science workshop at Cambridge University, this is one of a series of video pieces that reconstruct in the laboratory the effects of an earthquake on the lost island of Nuuk.

@newscientist

@CultureLabNS

#SFL15