Reading You Are Here: A field guide for navigating polarized speech, conspiracy theories, and our polluted media landscape by Whitney Phillips and Ryan M. Milner (MIT Press)

for New Scientist, 3 March 2021

This is a book about pollution, not of the physical environment, but of our civic discourse. It is about disinformation (false and misleading information deliberately spread), misinformation (false and misleading information inadvertently spread), and malinformation (information with a basis in reality spread pointedly and specifically to cause harm).

Communications experts Whitney Phillips and Ryan M. Milner completed their book just prior to the US presidential election that replaced Donald Trump with Joe Biden. That election, and the seditious activities that prompted Trump’s second impeachment, have clarified many of the issues Phillips and Milner have gone to such pains to explore. Though events have stolen some their thunder, You Are Here remains an invaluable snapshot of our current social and technological problems around news, truth and fact.

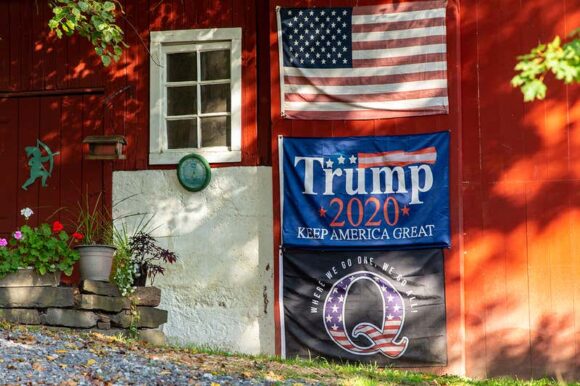

The authors’ US-centric (but universally applicable) account of “fake news” begins with the rise of the Ku Klux Klan. Its deliberately silly name, cartoonish robes, and quaint routines (which accompanied all its activities, from rallies to lynchings) prefigured the “only-joking” subcultures (Pepe the Frog and the like) dominating so much of our contemporary social media. Next, an examination of the Satanic panics of the 1980s reveals much about the birth and growth of conspiracy theories. The authors’ last act is an unpicking of QAnon — a current far-right conspiracy theory alleging that a secret cabal of cannibalistic Satan-worshippers plotted against former U.S. president Donald Trump. This brings the threads of their argument together in a conclusion all the more apocalyptic for being so closely argued.

Polluted information is, they argue, our latest public health emergency. By treating the information sphere as an ecology under threat, the authors push past factionalism to reveal how, when we use media, “the everyday actions of everyone else feed into and are reinforced by the worst actions of the worst actors”

This is their most striking takeaway: that the media machine that enabled QAnon isn’t a machine out of alignment, or out of control, or somehow infected: it’s a system working exactly as designed — “a system that damages so much because it works so well”.

This media machine is founded on principles that, in and of themselves, seem only laudable. Top of the list is the idea that to counter harms, we have to call attention to them: “in other words, that light disinfects”.

This is a grand philosophy, for so long as light is hard to generate. But what happens when the light — the confluence of competing information sets, depicting competing realities — becomes blinding?

Take Google as an example. Google is an advertising platform, that makes money the more its users use the internet to “get to the bottom of things”. The deeper the rabbit-holes go, the more money Google makes. This sets up a powerful incentive for “conspiracy entrepreneurs” to produce content, creating “alternative media echo-systems”. When the facts run out, create alternative facts. “The algorithm” (if you’ll forgive this reviewer’s dicey shorthand) doesn’t care. “The algorithm” is, in fact, designed to serve up as much pollution as possible.

What’s to be done? Here the authors hit a quite sizeable snag. They claim they’re not asking “for people to ‘remain civil’”. They claim they’re not commanding us, “don’t feed the trolls.” But so far as I could see, this is exactly what they’re saying — and good for them.

With the machismo typical of the social sciences, the authors call for “foundational, systematic, top-to-bottom change,” whatever that is supposed to mean, when what they are actually advocating is a sense of personal decency, a contempt for anonymity, a willingness to stand by what one says come hell or high water, politeness and consideration, and a willingness to listen.

These are not political ideas. These are qualities of character. One might even call them virtues, of a sort that were once particularly prized by conservatives.

Phillips and Milner bemoan the way market capitalism has swallowed political discourse. They teeter on a much more important truth: that politics has swallowed our moral discourse. Social media has made whining cowards of us all. You Are Here comes dangerously close to saying so. If you listen carefully, there’s a still, small voice hidden in this book, telling us all to grow up.