Reviewing The Aviator by Eugene Vodolazkin for The Guardian, 7 June 2018

Innokenty Petrovich Platonov, who lived through the Russian Revolution of 1917, has awoken, a hale and hearty thirtysomething, in a present-day hospital bed. Innokenty’s struggle – a long and compelling one, delivered with apparent leisureliness by the Ukrainian-born novelist Eugene Vodolazkin in a translation by Lisa Hayden – is to overcome his confusion, and connect his tragic past life to his uncertain present one over the gulf of years.

We’ve been here before. Think Tarkovsky’s 1975 film Mirror: a man’s life assembled out of jigsaw fragments that more or less resist narrative until the final minutes. Or think Proust. In The Aviator, an old translation of Defoe’sRobinson Crusoe replaces Marcel’s madeleine dipped in tea: “With each line,” Innokenty explains, “everything that accompanied the book in my time gone by was resurrected: my grandmother’s cough, the clank of a knife that fell in the kitchen … the scent of something fried, and the smoke of my father’s cigarette.”

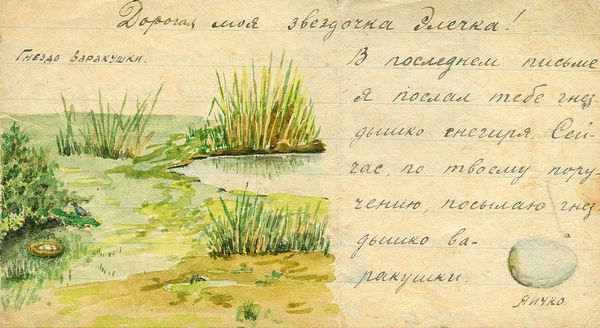

So far, so orthodox. But Vodolazkin’s grip on this narrative is iron-tight, and what we take at first to be Innokenty’s pathology – or the working out of a literary method – turns out to be something much more important: a moral stand, of sorts. Innokenty knows, in a bitter and visceral fashion, that history is merely a theory abstracted from the experiences of individuals. So he chooses to care about the little things, the overlooked things, “sounds, smells, and manners of expression, gesticulation, and motion”. These are the things that actually make up a life; these are the true universals.

A journalist interviews the celebrity time-traveller: “I keep trying to draw you out on historical topics and you keep talking about sounds and about smells.” He’s right: “A historical view makes everyone into hostages of great societal events,” Innokenty observes. “I see things differently, though: exactly the opposite.”

Innokenty has skin in this game: shortly before he was transported to the future, the Bolsheviks, history’s true believers, threw him into the first and worst of the labour camps. “Those who created the Solovetsky hell had deprived people of what was human,” Innokenty says, “but Robinson [Crusoe], after all, did the opposite: he humanised all the nature surrounding him, making it a continuation of himself. They destroyed every memory of civilisation but he created civilisation from nothing. From memory.” Inspired by his favourite book from childhood, Innokenty attempts a similar feat.

He discovers his old, unconsummated love still lives, hopelessly aged and now with dementia. He visits her, looks after her. He washes her, touching her for the first time; her granddaughter Nastya assists. He falls in love with Nastya, and navigates the taboos around their relationship with admirable delicacy and self-awareness. But Nastya is as much a child of her time as he is of his. They will love each other, but can never really bond, not because Nastya is a trivial person, but because she belongs to a trivial time, “a generation of lawyers and economists”. Modern faces are “nervous in some way”, Innokenty observes, “mean, an expression of ‘don’t touch me!’”

Innokenty is the ultimate internal exile: Turgenev’s ineffectual intellectual, played at an odd, more sympathetic speed. He is no more equipped to resist the blandishments of Zheltkov (the novel’s stand-in for Vladimir Putin), or the PR department of a frozen food company, than he was to resist the Soviet secret police. Innokenty’s attitude drives Geiger – his doctor, champion and friend – to distraction: how can this former prisoner of an Arctic labour camp possibly claim that “punishment for unknown reasons does not exist”?

Innokenty’s self-sacrificial piety provides his broken-backed life with a distinctly unmodern kind of meaning, and it’s one that leaves him hideously exposed. But we’re never in any doubt that his is a richer, kinder worldview than any available to Nastya. Innokenty’s bourgeois, liberal, pre-Bolshevik anguish over what constitutes right action is a surprisingly successful fulcrum on which to balance a book. And we should expect nothing less from an author whose previous novel, Laurus, was a barnstorming thriller about medieval virtue.

All that remains, I suppose, is to explain how this bourgeois “former person” comes to be alive in our own time, puzzling over the cult of celebrity, post-industrial consumerism and the internet. But why spoil the MacGuffin? Let’s just say, for now, that Innokenty has been preserved. “I did not even begin to question Geiger about the reasons, since that was not especially interesting,” he writes in his sprawling, revelatory journal. “Knowing the peculiarities of our country, it is simpler to be surprised that anything is preserved at all.”