On 12 April 1961 Yuri Gagarin clambered into Vostok I, blasted into space, and became the first human being to orbit the earth.

“And suddenly I hear: Man is in space! My God! I stopped heating up the oven, sat next to the radio receiver, afraid to step away even for a minute.” This is the recollection of a 73-year-old woman from the Kuibyshev region, published in the state newspaper Izvestiia a little over a month later.

“We were always told that God is in the heavens, so how can a man fly there and not bump into Elijah the Prophet or one of God’s angels? What if God punishes him for his insolence?… Now I am convinced that God is Science, is Man.”

The opposition between religion and science set up in this letter is charmingly naive — as though a space capsule might shatter the crystal walls of heaven! But the official Soviet attitude to these matters was not much different. Lenin considered religion “merely a product and reflection of the economic yoke within society.” Religion was simply a vicious exploitation of uneducated peoples’ urge to superstition. As socialism developed, superstitions in general would disappear, and religions along with them.

The art theorist Aleksey Gan called the constructivist Moscow Planetarium, completed in the late 1920s, “a building in which religious services are held… until society grows to the level of a scientific understanding, and the instinctual need for spectacle comes up against the real phenomena of the world and technology.”

The assumption here — that religion evaporates as soon as people learn to behave rationally — was no less absurd at the time than it is now; how it survived as a political instinct over generations is going to take a lot of explanation. Victoria Smolkin, an associate professor at Wesleyan University, delivers, but with a certain flatness of style that can grate after a while.

By 1973, with 70 planetariums littering the urban landscape and an ideologically oblivious populace gearing itself for a religious revival, I found myself wishing that her gloves would come off.

For the people she is writing about, the stakes could not have been higher. What can be more important than the meaning of life? We are all going to die, after all, and everything we do in our little lives is going to be forgotten. Had we absolutely no convictions about the value of anything beyond our little lives, we would most likely stay in bed, starving and soiling ourselves. The severely depressed do exactly this, for they have grown pathologically realistic about their survival chances.

Cultures are engines of enchantment. They give us reasons to get up in the morning. They give us people, institutions, ideas, and even whole planes of magical reality to live for.

The 1917 Revolution’s great blow-hards were more than happy to accept this role for their revolutionary culture. “Let thousands of us die to resurrect millions of people all over the earth!’ exclaims Rybin in Maxim Gorky’s 1906 novel Mother. “That’s what: dying’s easy for the sake of resurrection! If only the people rise!’ And in his two-volume Religion and Socialism, the Commissar of Education Anatoly Lunacharsky prophesies the coming of a culture in which the masses will wiillingly “die for the common good… sacrificing to realise a state that starts not with his ‘I’ but with our ‘we’.”

Given the necessary freedom and funding, perhaps the early Soviet Union’s self-styled “God-builders” — Alexander Bogdanov, Leon Trotsky and the rest — might have cooked up a uniquely Soviet metaphysics, with rituals for birth, marriage and death that were worth the name. In suprematism, constructivism, cosmism, and all the other millenarian “-isms” floating about at the turn of the century, Russia had no shortage of fresh ingredients.

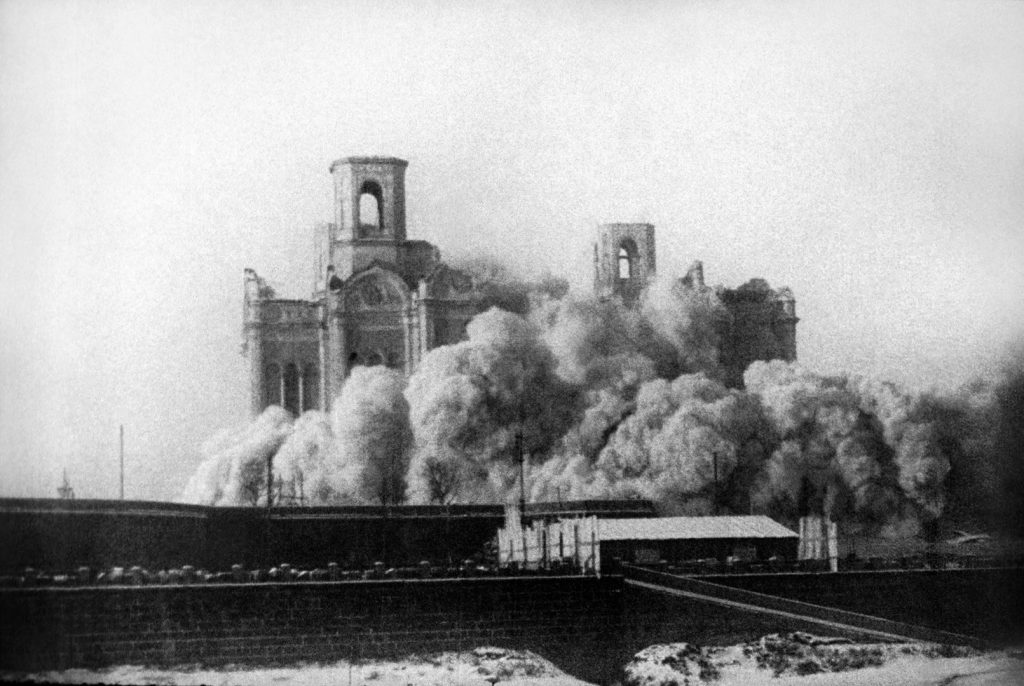

But Lenin’s lumpen anticlericals held the day. Bogdanov was sidelined and Trotsky was (literally) axed. Lenin looted the church. Stalin coopted the Orthodox faith to bolster patriotism in a time of war. Khrushchev criminalised all religions and most folk practices in the name of state unity. And none of them had a clue why the state’s materialism — even as it matured into a coherent philosophy — failed to replace the religion to which it was contrivedly opposed.

A homegrown sociology became possible under the fourth premier Leonid Brezhnev’s supposedly ossifying rule, and with it there developed something like a mature understanding of what religion actually was. These insights were painfully and often clumsily won — like Jack Skellington in Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas. trying to understand the business of gift-giving by measuring all the boxes under the tree. And the understanding, when it came, came far too late.

The price of generations of off-again, on-again religious repression was not a confident secularism, or even a convulsive religious reaction. It was poison: ennui and cynicism and ideological indifference that proved impossible for the state to oppose because it had no structure, no leaders, no flag, no clergy or dogma.

In the end there was nothing left but to throw in the towel. Mikhail Gorbachev met with Patriarch Pimen on 29 April 1988, and embraced the millennium as a national celebration. Konstantin Kharchev, chair of the Council for Religious Affairs, commented: “The church has survived, and has not only survived, but has rejuvenated itself. And the question arises: which is more useful to the party — someone who believes in God, someone who believes in nothing at all, or someone who believes in both God and Communism? I think we should choose the lesser evil.” (234)

Cultures do not collapse from war or drought or earthquake. They fall apart because, as the archaeologist Joseph Tainter points out, they lose the point of themselves. Now the heavy lifting of this volume is done, let us hope Smolkin takes a breath and describes the desolation wrought by the institutions she has researched in such detail. There’s a warning here that we, deep in our own contemporary disenchantment, should heed.