Mucking about on Windermere for FT Magazine, 31 March 2019

The Osprey, a steam launch built in 1902, carries me out on Lake Windermere. The ride is smooth, fast, virtually silent. I glance behind me, and for a few disconcerting seconds I am lost.

Where did we launch from? Where is Windermere Jetty, the region’s new “Museum of Boats, Steam and Stories”? Where are its enormous glass walls, to reveal its full-time restoration work to public view? Where are its gigantic eaves, to shield visitors from the rain?

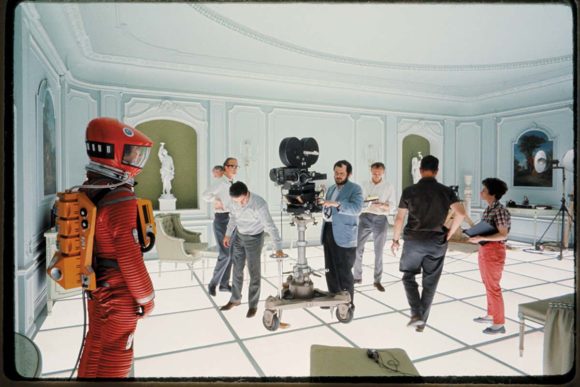

There’s an art to hiding in plain sight. Windermere Jetty — a series of unostentatious sheds designed by architects Carmody Groarke — is clad in copper, and even before its greenish patina appears, it’s blending easily with the darker tones of the surrounding trees.

Even if their colour made them stand out, these sheds would not immediately draw my eye. conditioned as I am by Arthur Ransome’s stories, and the Swallows and Amazons films, and a school syllabus besotted by the region’s literary history. I know what to expect from this view. The Jetty’s low, dark, massy wharf buildings, stuck right on the edge of the lake, obviously belong. The nearby Windermere Marina Village (a perfectly pleasant array of holiday apartments, carefully tucked away) obviously doesn’t.

In 1909, the zoologist Jacob von Uexküll proposed that animals only see what they need to see: the rest goes by virtually unnoticed. Tourism probably wasn’t at the forefront of his mind when he said this. But people are animals too. When we visit a place, we see what we already know about it, or what we have already been told about it, and the genuinely unexpected — especially in a place as loaded with expectation as the Lakes — is as likely to disappoint or irritate us as delight or surprise.

Why do the Lakes generate such strong feeling? Because they’re endangered? Or because they’re already spoiled? Spoiled how? By afforestation, by sheep, by the clumsy application of preservationist aspic? They’re not what they were, on this we can agree. But what were they? At Windermere Jetty, alongside elements of familiar Lakeland lore — steam kettles, childhood boating holidays, Beatrix Potter’s rowing boat mounted on one wall — other, more disconcerting aspects of the region are revealed: the Lakes as mining region, as testbed for new technologies, as strenuously guarded zone of wartime production. Sublime this place may be, from the right angles. But those scarps aren’t all ancient glacial erosion, and those hills, which haven’t seen a tree in eighty years, aren’t naturally bare. This is one of the most blatantly artificial landscapes in Europe.

From the polished deck of the Osprey, I slip under the spell of that period when wealthy industrialists built great houses along Windermere’s lake shore and ordered ostentatious steam launches to carry them to the railway head at Windermere. Men like Charles Fildes (Manchester: tin plate), who in winter took boiler and engine out of his private paddle steamer to use in his miniature railway. Or Col. John George Miller Ridehalgh (“King of the Lake”), who lit one of his several steamers with gas generated on board with a device straight out of a Heath-Robinson cartoon, driven by clockwork and a weight. Or William Henry Schneider (Barrow-in-Furness: iron production), who was so in love with his 65-foot steam yacht that he fitted it with an ice-cutting bow for winter use.

Like all seemingly timeless moments, this one lasted hardly any time at all. Windermere became a playground for Midlands industrialists around the middle of the nineteenth century and by the 1880s their great houses were already too big to manage. Henry Schneider turned Belsfield into a hotel while he was still living there: Ridehalgh’s seat, Fell Foot Park, was demolished in 1907.

Boats of better provenance than the Osprey are kept in dry dock. The Branksome cost around four times as much as the Osprey when it was built in 1896. The hull is constructed using 50 foot long lengths of varnished teak. The leather seats, the walnut panelling, the velvet upholstery and carpets are original.

It’s hard to hold in mind how advanced these craft were, and how important to the boating industry. Their designs, which derive ultimately from Windermere’s char-fishing boats of the Seventeenth century, were copied across Europe. (Their combination of stability and steerability also set the style for rowboats in every decent pleasure park in Britain.) “They could only have arisen in this place, at this moment,” says Rachel Roberts, head curator at the Jetty. Money was one ingredient in their manufacture. Because their backers were pioneer industrialists, an ambition to innovate — to be the fastest on the lake, or the most ostentatious — was another spur. Innovations from overseas were trialled here: the first American Chris-Craft boats. Planing hulls from Italy. World Speed records were broken here, repeatedly.

Windermere’s radical engineering culture long outlived the era of grand houses and their masters. On the Jetty’s roster for renovation is the steam launch Bat. In 1891, Jack Kitchen and Isaac Storey, two local radio pioneers, achieved a world first by steering it around the lake by radio remote control. (Kitchen already had form as an inventor: his reversing rudder, which could bring small ships to an almost complete stop in an instant, was picked up by the Royal Navy. His gas-powered gramophone and an elliptical wheel for difficult terrain fared less well.)

The region’s experimental engineering grew ever more baroque. The first British-built flying plane, the Waterhen, launched from Windermere in November 1911. It flew tourists around the lake safely for years, even as rival prototypes were falling out of the sky. Eleven years later someone thought it would be a good idea to build a power boat around a Rolls Royce 85 HP Mk1 Hawk airship engine. The Canfly looks terrifying enough in the museum. On the water it was a monster. You had to point the thing carefully down the centre of the lake before you cranked it to life because once the boat got moving there was no easy way to steer. The only way to stop it was to cut the engine.

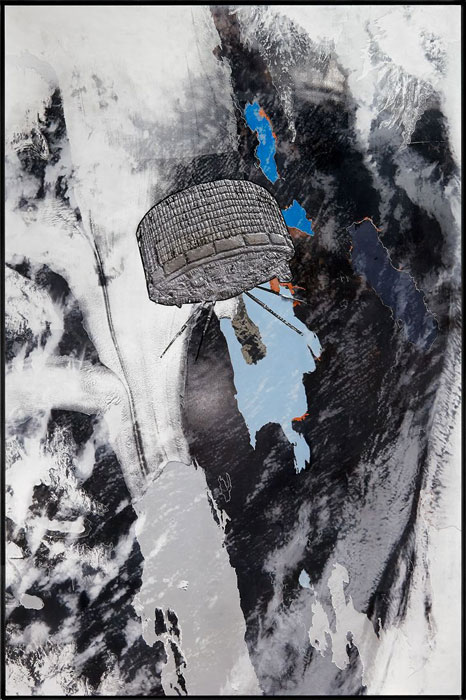

Roberts leads me to exhibits that reveal where all this well-funded innovation was ultimately bound: the killing fields of the following century. Sail lost its dominance on the lake when local sailmakers were put to manufacturing sand-bags in the First World War. Over the course of the Second World War, 500 people were employed to turn out 35 gigantic Shorts Sunderland Flying Boats: key machines in the Allies’ airborne Atlantic defence. “These,” she says, pointing to a picture of the factory, which stood not far from here, “were the largest single-span buildings in Europe.”

Defended by D company, 9th Lakes Battalion, who patrolled Lake Windermere with four speed boats and two houseboats, all equipped with machine guns, the workers lived more or less over the shop in the purpose-built village of Calgarth. Afterwards, the village was used to house and recuperate 300 child victims of the Holocaust.

“Wars transform the whole character of a place,” says Roberts, though she doesn’t mention the biggest wartime transformation of all.

More or less everything we think about the Lake District is an artefact of the Napoleonic Wars. Between 1799 and 1815, conflict brought to a halt the sort of comfortable European travel young intellectuals expected from their Grand Tour.

With the wonders of the mainland put out of bounds, the Lakes provided a homegrown locus for the cultivation of finer feeling — and it’s a role the region still fulfils today, at least for those of a sufficiently Romantic temperament. “Here,” wrote the publisher Rudolph Ackerman, in his Picturesque Tour of the English Lakes (1821) “we have valleys of the utmost softness and beauty, luxuriantly wooded and watered by these enchanting lakes and the crystal streams which flow from them, deeply embosomed amidst lofty mountains, whose sides exhibit wild rocks majestically piled on each other, with yawning gulfs between, down which foaming torrents descend from dark and gloomy Tarns…”

But by then, the natural Lakeland landscape was already a thing of the past. From about 1300 the monks of Furness Abbey had been scouring the hills for iron and felling woods for charcoal. Iron, to feed the first factories of the Industrial Revolution, drove the Lakeland economy for decades. Copper was another important mining activity, turning the whole massif of the Coniston Fells to scree. The blighted wildernesses of Old Man of Coniston and Honister Pass are what’s left of the trade in slate, to roof the houses of 19th-century Midlands towns during the boom. There’s much local opposition at the moment to plans to construct a zip-wire across the Honister Pass, from Borrowdale to Buttermere. But it’s not such an outlandish idea: blocks of slate were once removed from the mountain but just such a wire. There are photographs. There was also an incline system, and the Honister Crag Railway, and a tramway which ran right up until 1962.

We assume the Lake District is under threat by throngs of tourists. In his Guide to the Lakes in 1810, Wordsworth lamented how his “Republic of Shepherds and Agriculturists” was ceding ground to a culture of railway tourism. Nowhere in the index, however, will you find any reference to coal, copper, industry, iron, or mines.

Today 18 million of us clog the narrow lanes of England’s Lake District each year, and Carlisle Lake District Airport, a half-hour drive from Penrith will only add to the burden when it opens this July. Still, we tend to blank the fact that the Lake District is an industrial site, characterised (in George Monbiot’s memorable formulation) by “quad bikes, steel barns and absentee ownership”.

The Lake District knows what to do with visitors. It builds industries around them. The first public steamer on Windermere, the Lady of the Lake, was launched the same year the Great Britain sailed from Liverpool to New York. A rival company sprang up to take advantage of the fast-improving technology. Its flagship used to shoot past the Lady with the band playing “The Girl I Left Behind Me”.

Today the region responds similarly: by swinging squealing youths from wires that in another age would have carried stones. By trialing driverless pods, so as to prise visitors out of their cars. On nearby Coniston, a steamer restored by the National Trust vies for trade with two ferries driven by solar power.

Stephen Beresford, Windermere Jetty’s senior conservation boat builder, shows me round the working part of the museum, where local apprentices will learn how to build and restore a collection whose provenance stretches from 1780 to 1983. “The trick,” says Beresford, a civil engineer turned historic boat restorer, “is to know what you can and can’t replace.” Time is real, and cannot be frozen. Imagination, technique and craft are the way we connect to the past. Every vessel in this museum could go back on the water if he replaced everything. “And by the time we got it back into the water there’d be so little of it left, it’d no longer be historic. Would it?”