Author Archives: simonings

The Suspicions of Mr Whicher or the Murder at Road Hill House by Kate Summerscale

Physics of the Impossible by Michio Kaku

Learning to love robots

London, 1977: the international grandmaster Michael Stean is losing to Chess 4.6, a computer programme developed at Northwestern University, Illinois. Stean is steamed: he is losing. Chess 4.6 is, he says, “an iron monster”. When finally he admits defeat, however, he does so with grace, declaring 4.6 a genius.

Whether we’re leaving it all to the cat, or thrashing an Austin 1300 estate with a stick, we anthropomorphise as much of the world as we can. Twelve thousand years ago we took wild animals and fashioned them in our image: domestic cats have evolved babyish complexions to appeal to our love of cute.

Anthropomorphism, although apparently a sentimental tic, is central to what makes us human. A baby’s realisation that other people are more than animated furniture develops over time, prompted and reinforced by a pattern of exchanged glances. Long before children acquire this understanding (called theory of mind), they are fascinated by eyes, and by the direction of another’s gaze. We become human only because, early on, someone treated us as human.

Advertisement

How complex does something have to be before it passes as human? The answer seems to be not very. A consortium led by the University of Plymouth has just won a £4.7m grant to teach a humanoid robot named iCub how to speak English. Its theory of mind may depend less on intellectual potential than on the scientists’ willingness to treat their charge like a real infant.

Let’s hope it grows into a sociable little thing. The bald fact is, we need him. The US Census Bureau has estimated that the nation’s elderly population will more than double by 2050, to 80 million. But there are simply not enough young to look after them. A study by Saint Louis University, Missouri, shows robot dogs are as much of a comfort to the elderly as real dogs. In 30 years, robot carers will be required for practical help, as well as solace, for old people.

Sign up for Lab Notes – the Guardian’s weekly science update

Read more

Domestic robots are already big business. The sale of service robots in Japan is expected to top £5bn by 2015. Mind is the final hurdle, but robots don’t have to be as clever as us to care for us, converse with us, or accompany us. They just have to be clever enough. Our instinct for anthropomorphism will do the rest.

This, anyway, is the message of Love and Sex with Robots, a book by David Levy. A chess international master, Levy was driven by his passion for artificial intelligence to lead the team that created Converse – a programme which, in 1997, won the Loebner prize, an award for the most convincing computer conversationalist.

Now in his mid-60s, Levy is bringing artificial life to sex. “Humans long for affection and tend to be affectionate to those who offer it,” he says, and predicts that prostitution has only about another 20 years to run before robots take over. Robots with credibly human bodies are already here. Add minds clever enough to handle a little language, and how could we possibly avoid loving them?

Levy argues that robots will appeal to our better natures. It has already happened. Remember those Japanese toys you had to “feed” at all hours of the night? “A remarkable aspect of the Tamagotchi’s huge popularity,” writes Levy, “is that it possesses hardly any elements of character or personality, its great attraction coming from its need for almost constant nurturing.”

His book reminds us that humanity is an act: it is something we do. When our robots become pets, carers, even companions, we will, quite naturally, feel the urge to treat them well. When it comes to being human, we will give them the benefit of the doubt, the way we give the benefit of the doubt to our pets, our children, and each other.

The Canon: the Beautiful Basics of Science by Natalie Angier

Shuffling symmetries

How many symmetries can you find in the letter that begins this sentence? You will probably count the symmetries to do with reflection – swapping the “H” left-to-right, up-to-down and across diagonals – before you think to add a rotational symmetry to the list, turning the letter through 180 degrees. If you could pick the letter up, you could also flip it over: another rotational symmetry. If you turned it around and then flipped it over, would this be the same as flipping it over and turning it around?

How would you find out? The whole point about symmetry is that it allows an object to change its orientation without altering its appearance. This can be a headache even when handling two-dimensional objects. Ever tried feeding letterhead paper into an unfamiliar printer? Now imagine handling a 196,883-dimensional object.

Reading takes time, and time destroys symmetry. Nonetheless, Du Sautoy has invested a lot in creating a very symmetrical book, one whose ends are thinner than its middle. We begin and end gently. Symmetry appears in the real world, metastasizes through multidimensional space, then returns to earth for a long, gentle decompression.

To start with, we are told that symmetry has prestige. It’s expensive to do: only the fittest and healthiest plants and animals can afford to devote resources to it. So symmetry carries meaning: it is a sign of success. Symmetry has cultural prestige for the same reason: without access to mass-manufacture, symmetrical objects are hard to craft. Near the end of Du Sautoy’s account we hear symmetry in music, discover a connection between symmetry and empathy, and we see why, although symmetrical shapes are hard for living things of any size to achieve, they are easy for things that are very small. Some viruses are Platonic solids – objects that are symmetrical in three dimensions. Death, more often than not, has 20 faces: herpes, rubella and HIV are all icosahedrons.

The real work of the book is its middle. Some objects are more symmetrical than others, and this is as true of hypothetical, impossible-to-visualise multidimensional objects as it is of dice and bathroom tiles. How do we find symmetrical objects we can’t see – and how do we work out how their symmetries relate? In the middle of the 20th century, a branch of mathematics called group theory devoted 30 years to an exhaustive hunt for new species of multidimen-sional symmetry. This hunt shared some qualities with astronomy. Just when you think your account of the cosmos is complete, someone working on another continent rings up to report something inexplicable.

To bring us up to speed with group theory, Du Sautoy rattles through a lot of history. There is not a lot else he can do. The best way of explaining maths is through the history of maths. The history is not really the point – and this is as well, since he unapologetically describes in geometrical terms much work that acquired its relevance for symmetry only much later. Du Sautoy’s strategy places clarity a long way above precision. His hope is that the reader can visualise, more than understand. “A child starting out on an instrument will have no idea… how to improvise a blues lick, yet they can still get a kick out of hearing someone else do it.” Finding Moonshine is a superlative mathematical entertainment; not pretty to the purist eye, but oh, so effective.

Du Sautoy adds whig memoir to whig history when he harnesses himself and his family to his account. He neatly captures his spiky relations with his son Tomer; at one point he tells him off for using his Nintendo, only to discover the poor kid was using it to study the very symmetries his father lives for. Attempts to personalise a subject in this way are not to everyone’s taste, but his account of a family visit to the Alhambra (pictured left), home to all 17 two-dimensional symmetries, has won him at least one convert.

Most of symmetry’s big game hunters used mathematics to hide from life. They developed techniques “almost like the craft skills of the medieval stone-masons”. Now, for all their awards, they are yesterday’s men. The mathematical experience is a stark one, lived out in a world where superhuman flights of analytical thinking shade seemlessly into autistic compulsions; where trust is tricky, and success can make you redundant; and no-one, not even your your family, will ever understand why you are smiling. Du Sautoy tells us that when he was a child, he wanted to grow up to be a secret agent.

In a funny way, he got his wish.

Maths into English

One to Nine by Andrew Hodges and The Tiger that Isn’t by Michael Blastland and Andrew Dilnot

reviewed for the Telegraph, 22 September 2007

Twenty-four years have passed since Andrew Hodges published his biography of the mathematician Alan Turing. Hodges, a long-term member of the Mathematical Physics Research Group at Oxford, has spent the years since exploring the “twistor geometry” developed by Roger Penrose, writing music and dabbling with self-promotion.

Follow the link to One to Nine’s web page, and you will soon be stumbling over the furniture of Hodges’s other lives: his music, his sexuality, his ambitions for his self?published novel – the usual spillage. He must be immune to bathos, or blind to it. But why should he care what other people think? He knows full well that, once put in the right order, these base metals will be transformed.

“Writing,” says Hodges, “is the business of turning multi?dimensional facts and ideas into a one?dimensional string of symbols.”

One to Nine – ostensibly a simple snapshot of the mathematical world – is a virtuoso stream of consciousness containing everything important there is to say about numbers (and Vaughan Williams, and climate change, and the Pet Shop Boys) in just over 300 pages. It contains multitudes. It is cogent, charming and deeply personal, all at once.

“Dense” does not begin to describe it. There is extraordinary concision at work. Hodges covers colour space and colour perception in two or three pages. The exponential constant e requires four pages. These examples come from the extreme shallow end of the mathematical pool: there are depths here not everyone will fathom. But this is the point: One to Nine makes the unfathomable enticing and gives the reader tremendous motivation to explore further.

This is a consciously old-fashioned conceit. One to Nine is modelled on Constance Reid’s 1956 classic, From Zero to Infinity. Like Reid’s, each of Hodges’s chapters explores the ideas associated with a given number. Mathematicians are quiet iconoclasts, so this is work that each generation must do for itself.

When Hodges considers his own contributions (in particular, to the mathematics underpinning physical reality), the skin tightens over the skull: “The scientific record of the past century suggests that this chapter will soon look like faded pages from Eddington,” he writes. (Towards the end of his life, Sir Arthur Eddington, who died in 1944, assayed a “theory of everything”. Experimental evidence ran counter to his work, which today generates only intermittent interest.)

But then, mathematics “does not have much to do with optimising personal profit or pleasure as commonly understood”.

The mordant register of his prose serves Hodges as well as it served Turing all those years ago. Like Turing: the Enigma, One to Nine proceeds, by subtle indirection, to express a man through his numbers.

If you think organisations, economies or nations would be more suited to mathematical description, think again. Michael Blastland and Andrew Dilnot’s The Tiger that Isn’t contains this description of the International Passenger Survey, the organisation responsible for producing many of our immigration figures:

The ferry heaves into its journey and, equipped with their passenger vignettes, the survey team members also set off, like Attenboroughs in the undergrowth, to track down their prey, and hope they all speak English. And so the tides of people swilling about the world?… are captured for the record if they travel by sea, when skulking by slot machines, half?way through a croissant, or off to the ladies’ loo.

Their point is this: in the real world, counting is back-breaking labour. Those who sieve the world for numbers – surveyors, clinicians, statisticians and the rest – are engaged in difficult work, and the authors think it nothing short of criminal the way the rest of us misinterpret, misuse or simply ignore their hard-won results. This is a very angry and very funny book.

The authors have worked together before, on the series More or Less – BBC Radio 4’s antidote to the sort of bad mathematics that mars personal decision-making, political debate, most press releases, and not a few items from the corporation’s own news schedule.

Confusion between correlation and cause, wild errors in the estimation of risk, the misuse of averages: Blastland and Dilnot round up and dispatch whole categories of woolly thinking.

They have a positive agenda. A handful of very obvious mathematical ideas – ideas they claim (with a certain insouciance) are entirely intuitive – are all we need to wield the numbers for ourselves; with them, we will be better informed, and will make more realistic decisions.

This is one of those maths books that claims to be self?help, and on the evidence presented here, we are in dire need of it. A late chapter contains the results of a general knowledge quiz given to senior civil servants in 2005.

The questions were simple enough. Among them: what share of UK income tax is paid by the top one per cent of earners? For the record, in 2005 it was 21 per cent. Our policy?makers didn’t have a clue.

“The deepest pitfall with numbers owes nothing to the numbers themselves and much to the slack way they are treated, with carelessness all the way to contempt.”

This jolly airport read will not change all that. But it should stir things up a bit.

Unknown Quantity: a Real and Imagined History of Algebra by John Derbyshire

Unknown Quantity: a Real and Imagined History of Algebra by John Derbyshire

reviewed for the Telegraph, 17 May 2007

In 1572, the civil engineer Rafael Bombelli published a book of algebra, which, he said, would enable a novice to master the subject. It became a classic of mathematical literature. Four centuries later, John Derbyshire has written another complete account. It is not, and does not try to be, a classic. Derbyshire’s task is harder than Bombelli’s. A lot has happened to algebra in the intervening years, and so our expectations of the author – and his expectations of his readers – cannot be quite as demanding. Nothing will be mastered by a casual reading of Unknown Quantity, but much will be glimpsed of this alien, counter-intuitive, yet extremely versatile technique.

Derbyshire is a virtuoso at simplifying mathematics; he is best known for Prime Obsession (2003), an account of the Riemann hypothesis that very nearly avoided mentioning calculus. But if Prime Obsession was written in the genre of mathematical micro-histories established by Simon Singh’s Fermat’s Last Theorem, Derbyshire’s new work is more ambitious, more rigorous and less cute.

It embraces a history as long as the written record and its stories stand or fall to the degree that they contribute to a picture of the discipline. Gone are Prime Obsession’s optional maths chapters; in Unknown Quantity, six “maths primers” preface key events in the narrative. The reader gains a sketchy understanding of an abstract territory, then reads about its discovery. This is ugly but effective, much like the book itself, whose overall tone is reminiscent of Melvyn Bragg’s Radio 4 programme In Our Time: rushed, likeable and impossibly ambitious.

A history of mathematicians as well as mathematics, Unknown Quantity, like all books of its kind, labours under the shadow of E T Bell, whose Men of Mathematics (1937) set a high bar for readability. How can one compete with a description of 19th-century expansions of Abel’s Theorem as “a Gothic cathedral smothered in Irish lace, Italian confetti and French pastry”?

If subsequent historians are not quite left to mopping-up operations, it often reads as though they are. In Unknown Quantity, you can almost feel the author’s frustration as he works counter to his writerly instinct (he is also a novelist), applying the latest thinking to his biography of the 19th-century algebraist Évariste Galois – and draining much colour from Bell’s original.

Derbyshire makes amends, however, with a few flourishes of his own. Also, he places himself in his own account – a cultured, sardonic, sometimes self-deprecating researcher. This is not a chatty book, thank goodness, but it does possess a winning personality.

Sometimes, personality is all there is. The history of algebra is one of stops and starts. Derbyshire declares that for 269 years (during the 13th, 14th and early 15th centuries) little happened. Algebra is the language of abstraction, an unnatural way of thinking: “The wonder, to borrow a trope from Dr Johnson, is not that it took us so long to learn how to do this stuff; the wonder is that we can do it at all.”

The reason for algebra’s complex notation is that, in Leibniz’s phrase, it “relieves the imagination”, allowing us to handle abstract concepts by manipulating symbols. The idea that it might be applicable to things other than numbers – such as sets, and propositions in logic – dawned with tantalising slowness. By far the greater part of Derbyshire’s book tells this tale: how mathematicians learned to let go of number, and trust the terrifying fecundity of their notation.

Then, as we enter the 20th century, and algebra’s union with geometry, something odd happens: the mathematics gets harder to do but easier to imagine. Maths, of the basic sort, is a lousy subject to learn. Advanced mathematics is rich enough to sustain metaphor, so it is in some ways simpler to grasp.

Derbyshire’s parting vision of contemporary algebra – conveyed through easy visual analogies, judged by its applicability to physics, realised in glib computer graphics – is almost a let-down. The epic is over. The branches of mathematics have so interpenetrated each other, it seems unlikely that algebra, as an independent discipline, will survive.

This is not a prospect Derbyshire savours, which lends his book a mordant note. This is more than an engaging history; it records an entire, perhaps endangered, way of thinking.

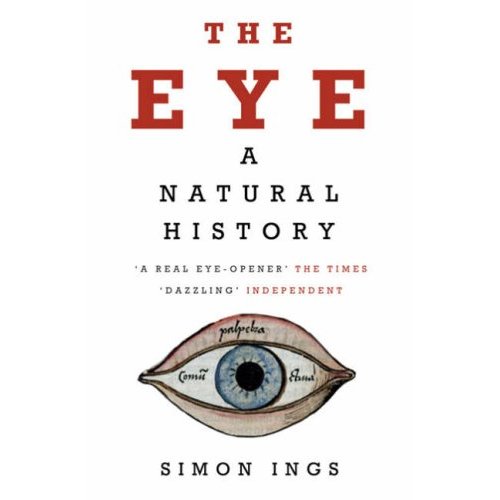

The Eye: a Natural History

This is a book about the nature of the eye. It is about all the eyes that are, and ever have been, and may yet be. It is about how we see the world, and how other eyes see it. It is about what happens to the world when it is looked at, and about what happens to us when we look at each other. It is about evolution, chemistry, optics, colour, psychology, anthropology, and consciousness. It is about what we know, and it is also about how we came to know it. So this is also a book about personal ambition, folly, failure, confusion, and language.

You can buy The Eye: A Natural History at Amazon.co.uk

Amazon.com has the American edition, A Natural History of Seeing

UK: Bloomsbury. 1st hardback edition, March 2007

UK: Bloomsbury. Paperback, January 2008

Germany: Hoffman und Campe, April 2008

USA: Norton, October 2008

Italy: Einaudi, October 2008

Japan: Hayakawa, 2008

Portugal: Aletheia, 2008

The Eye: what the reviewers said

Doug Johnstone, The Times, March 10, 2007

Graham Farmelo, Sunday Telegraph, March 24

P D Smith, the Guardian, June 2

Marcus Berkmann, The Spectator, March 31

(requires subscription; the review has been reprinted here)

Gail Vines, the Independent, April 25

Robert Hanks, the Telegraph, March 18

There are fascinating facts galore: our eyes are never still, for example. As well as entertaining, it’s philosophically profound: showing how our eyes, far from simply absorbing the world, are tools with which we construct our own reality.

Katie Owen, the Sunday Telegraph, 27 January 2008

Hermione Buckland-Hoby, the Observer, January 27

Ross Leckie, The Times January 25

Ian Critchley, The Sunday Times, January 27

the Telegraph, February 2