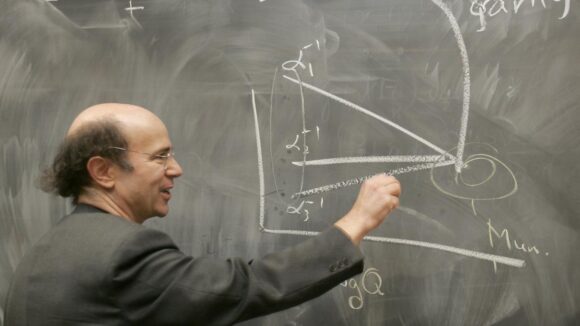

Reading Fundamentals by Frank Wilczek for the Times, 2 January 2021

It’s not given to many of us to work at the bleeding edge of theoretical physics, discovering for ourselves the way the world really works.

The nearest most of us will ever get is the pop-science shelf, and this has been dominated for quite a while now by the lyrical outpourings of Italian theoretical physicist Carlo Rovelli. Rovelli’s upcoming one, Helgoland, promises to have his reader tearing across a universe made, not of particles, but of the relations between them.

It’s all too late, however: Frank Wilczek’s Fundamentals has gazzumped Rovelli handsomely, with a vision that replaces our classical idea of physical creation — “atoms and the void” — with one consisting entirely of spacetime, self-propagating fields and properties.

Born in 1951 and awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2004 for figuring out why atoms don’t just fly apart, Wilczek is out to explain why “the history of Sweden is more complicated than the history of the universe”. The ingredients of the universe are surprisingly simple, but their fates, playing out through time in accordance with just a handful of rules, generate a world of unimaginable complexity, contingency and abundance. Measures of spin, charge and mass allow us to describe the whole of physical reality, but they won’t help us at all in depicting, say, the history of the royal house of Bernadotte.

Wilczek’s “ten keys to reality”, mentioned in his subtitle, aren’t to do with the 19 or so physical constants that exercised Martin Rees, the UK’s Astronomer Royal, in his 1990s pop-science heyday. The focus these days has shifted more to the spirit of things. When Wilczek describes the behaviour of electrons around an atom, for example, gone are the usual Böhr-ish mechanics, in which electrons leap from one nuclear orbit to another. Instead we get a vibrating cymbal, the music of the spheres, a poetic understanding of fields, and not a fragment of matter in sight.

So will you plump for the Wilzcek, or will you wait for the Rovelli? A false choice, of course; this is not a race. Popular cosmology is more like the jazz scene: the facts (figures, constants, models) are the standards everyone riffs off. After one or two exposures you find yourself returning for the individual performances: their poetry, their unique expression.

Wilczek’s ten keys are more like ten book ideas, exploring the spatial and temporal abundance of the universe; how it all began; the stubborn linearity of time; how it all will end. What should we make of his decision to have us swallow the whole of creation in one go?

In one respect this book was inevitable. It’s what people of Wilczek’s peculiar genius and standing do. There’s even a sly name for the effort: the philosopause. The implication here being that Wilczek has outlived his most productive years and is now pursuing philosophical speculations.

Wilzcek is not short of insights. His idea of what the scientific method consists of is refreshingly robust: a style of thinking that “combines the humble discipline of respecting the facts and learning from Nature with the systematic chutzpah of using what you think you’ve learned aggressively”. If you apply what you think you’ve discovered everywhere you can, even in situations that have nothing to do with your starting point, then, if it works, “you’ve discovered something useful; it it doesn’t, then you’ve learned something important.”

However, works of the philosopause are best judged on character. Richard Dawkins seems to have discovered, along with Johnny Rotten, that anger is an energy. Martin Rees has been possessed by the shade of that dutiful bureaucrat C P Snow. And in this case? Wilczek, so modest, so straight-dealing, so earnest in his desire to conciliate between science and the rest of culture, turns out to be a true visionary, writing — as his book gathers pace — a human testament to the moment when the discipline of physics, as we used to understand it, came to a stop.

Wilczek’s is the first generation whose intelligence — even at the far end of the bell-curve inhabited by genius — is insufficient to conceptualise its own scientific findings. Machines are even now taking over the work of hypothesis-making and interpretation. “The abilities of our machines to carry lengthy yet accurate calculations, to store massive amounts of information, and to learn by doing at an extremely fast pace,” Wilczek explains, “are already opening up qualitatively new paths toward understanding. They will move the frontier of knowledge in directions, and arrive at places, that unaided human brains can’t go.”

Or put it this way: physicists can pursue a Theory of Everything all they like. They’ll never find it, because if they did find it, they wouldn’t understand it.

Where does that leave physics? Where does that leave Wilczek? His response is gloriously matter-of-fact:

“… really, this should not come as fresh news. Humans themselves know many things that are not available to human consciousness, such as how to process visual information at incredible speeds, or how to make their bodies stay upright, walk and run.”

Right now physicists have come to the conclusion that the vast majority of mass in the universe reacts so weakly to the bits of creation we can see, we may never know its nature. Though Wilczek makes a brave stab at the problem of so-called “dark matter”, he is equally prepared to accept that a true explanation may prove incomprehensible.

Human intelligence turns out to be just one kind of engine for understanding. Wilzcek would have us nurture it and savour it, and not just for what it can do, but because it is uniquely ours.