Exhibitions hitch themselves to the 500th anniversary of Leonardo da Vinci at their peril. How do you do justice to a man whose life’s work provides the soundtrack to your entire culture? Leonardo dabbled his way into every corner of intellectual endeavour, and carved out several tasty new corners into the bargain. For heaven’s sake, he dreamt up a glass vessel to demonstrate the dynamics of fluid flow in the aortic valve of the human heart: modern confirmation that he was right (did you doubt it?) had to wait for the cardiologist Robin Choudhury and a paper written in 2014.

Daryl Green and Laura Moretti, curators of Thinking 3D at Oxford’s Weston Library, are wise to park this particular story at the far end of their delicate, nuanced, spiderweb of an exhibition into how artists and scientists, from Leonardo to now, have learned to convey three-dimensional objects on the page.

Indeed they do very good job of keeping You Know Who contained. This is a show made up of books, mostly, and Leonardo came too soon to take full advantage of print. He was, anyway, far too jealous of his own work to consign it to the relatively crude reproductive technologies of his day. Only one of his drawings exists in printed form — a stellated dodecahedron, drawn for his friend Luca Pacioli’s De Divina Proportione of 1509. It’s here for the viewing, alongside other contemporary attempts at geometrical drawing. Next to Leonardo, they are hardly more than doodles.

A few of Leonardo’s actual drawings — the revolving series here is drawn from the Royal Collection and the British Library — served to provoke, more than to inspire, the advances in 3D visualisation that followed. In a couple of months the aortic valve story will be pulled from the show, its place taken by astrophysicist Steven Balbus’s attempts to visualise black holes. (There’s a lot of ground to cover, and very little room, so the exhibition will be changing some elements regularly during the run.) When that happens, will Leonardo’s presence in this exhibition begin to feel gratuitous? Probably not: Leonardo is the ultimate Man Who Came to Dinner: once put inside your head there’s no getting rid of him.

Thinking 3D is more than just this exhibition: the year-long project promises events, talks, conferences and workshops, not to mention satellite shows. (Under the skin: illustrating the human body, which just ended at the Royal College of Physicians in London, was one of these.) The more one learns about the project, the more it resembles Stephen Leacock’s Lord Ronald, who flung himself upon his horse and rode madly off in all directions — and the more impressive the coherence Green and Moretti have achieved here.

There are some carefully selected geegaws. A stereoscope through which one can study Arthur Thomson stereographic Anatomy of the Human Eye, published in 1912. The nation’s first look at Bill Gates’s Codescope, an interactive kiosk with a touch screen that lets you explore the Codex Leicester, a notebook of Leonardo’s that Gates bought in 1994. Even a shelf full of 3D-printed objects you are welcome to fondle, like Linus with his security blanket, as you wander around the exhibition. This last jape works better than you’d think: by relating vision to touch, it makes us properly aware of all the mental tricks we have to perform, in order to to realise 3D forms in pictures.

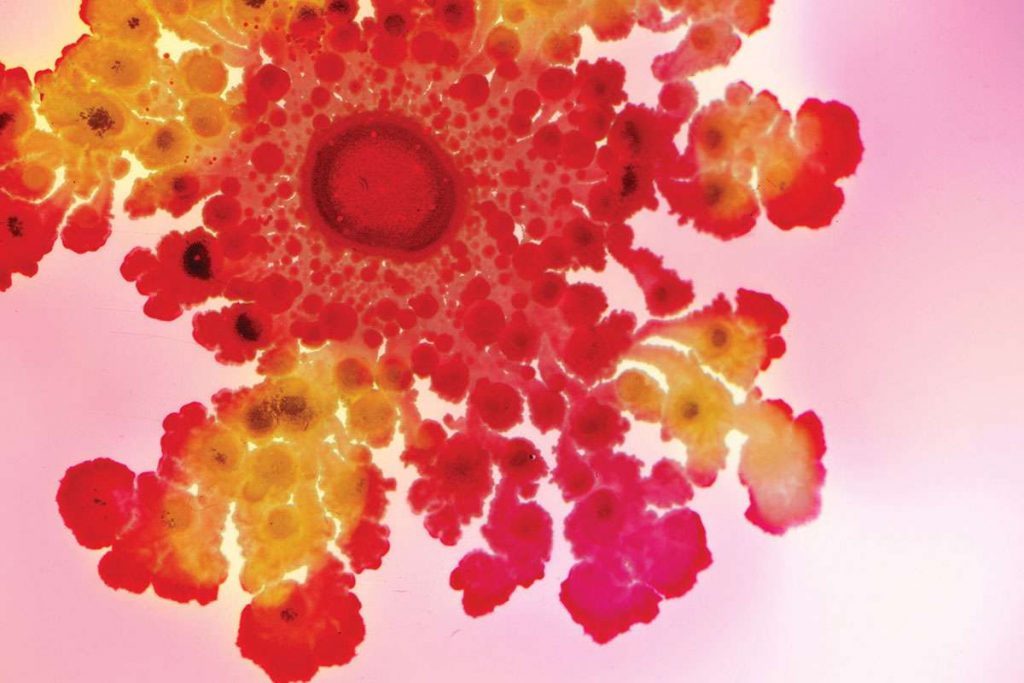

But books are the meat of the matter: arranged chronologically along one wall, and under glass in displays that show how the same theme has been handled at different times. Start at the clean, complex lines of the dodecahedron and pass, via architecture (the coliseum) and astronomy (the Moon) to the fleshy ghastliness of the human eyeball.

Conveying depth by drawing makes geometry comprehensible. It also, and in particular, transforms three areas of fundamental intellectual enquiry: anatomy, architecture, and astronomy.

Today, when we think of 3D visualisation, we think first of architecture. (It’s an association forged, in large part, in the toils of countless videogames: never mind the plot, gawp at all that visionary pixelcrete!). But because architecture operates at a more-or-less human-scale, it’s actually been rather slow to pick up on the power of 3D visualisation. With intuition and craft skill to draw upon, who needs axonometry? The builders of the great Mediaeval cathedrals managed quite happily without any such hifalutin drawing techniques, and it wasn’t until Auguste Choisy’s Histoire de l’architecture of 1899 that a drawing style that had already transformed carpentry, machinery, and military architecture finally found favour with architects. (Arguably, the profession has yet to come down off the high this occasioned. Witness the number of large buildings that look, for all their bulk, like scale models, their shapes making sense only from the most arbitrary angles.)

Where the scale is too small or too large for intuition and common sense to work, 3D visualisation has been most useful, and most beautiful. Andreas Vesalius’s De humani corporis fabrica librorum epitome (1543) stands here for an entire genre of “fugitive sheets” — compendiums of exquisite anatomical drawings with layered flaps, peeled back by the reader to reveal the layers of the body as one might discover them during a dissection. Because these documents were practical surgical guides, they received rough treatment, and hardly any survive. Those that do (though not the one here, thank God) are often covered with mysterious stains.

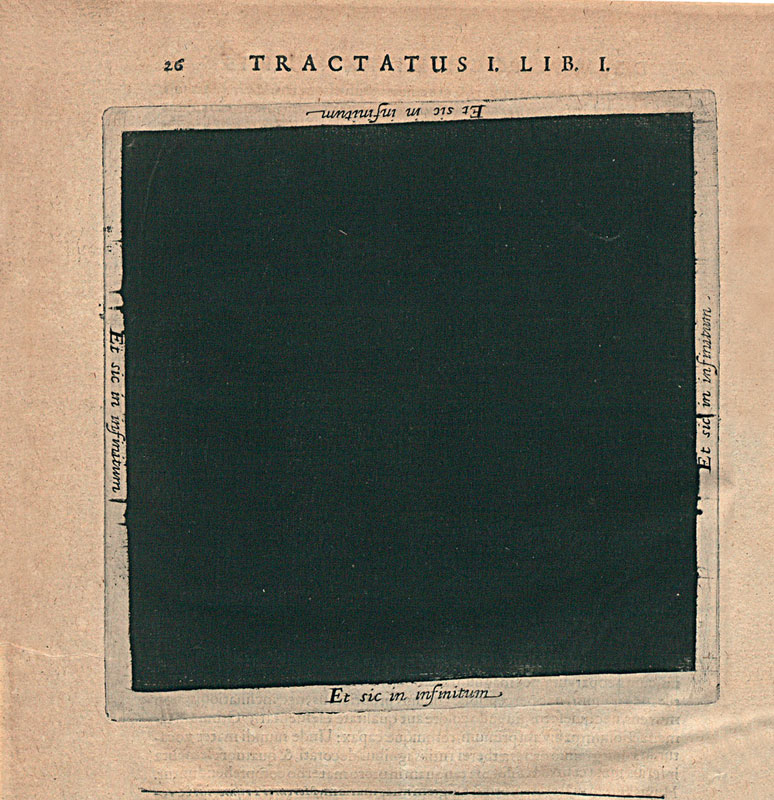

Less gruesome, but at the same time less immediately communicative, are the various attempts here to render the cosmos on paper. Robert Fludd’s black square from his Utriusque Cosmi (1617-21), depicts the void immediately prior to creation. Et sic in infinitum (“And so on to infinity”) run the words on each side of this eloquent blank.

Thinking 3D explores territories where words tangle incoherently and only pictures will suffice — then leaps giggling into a void where rational enquiry collapses and only artworks and acts of mischief like Fludd’s manage to convey anything at all. All this in a space hardly bigger than two average living rooms. It’s a show that repays — indeed, demands — patience. Put in the requisite effort, though, and you’ll find it full of wonders.

Happy Chat Beast tries to be good in Feed Me © 2013, Rachel Maclean

Happy Chat Beast tries to be good in Feed Me © 2013, Rachel Maclean