Visiting mumok, Vienna’s museum of contemporary art, for New Scientist, 23 December 2017

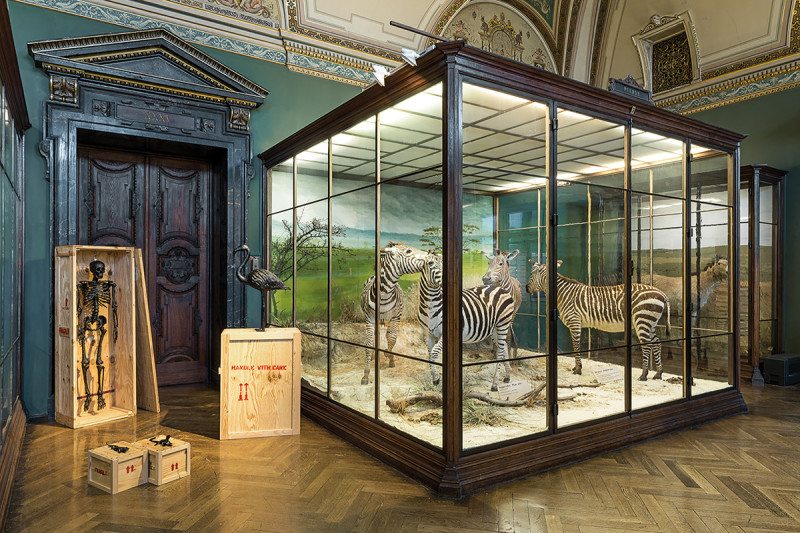

Visitors to Vienna’s spectacular Natural History Museum may discover some taxidermied exhibits smothered in black gloop. This is artist Mark Dion’s The Tar Museum, and it is part of Natural Histories: Traces of the Political, an art exhibition about nature and politics, most of which is in the nearby museum of contemporary art, mumok.

Those venturing across the Maria-Theresien-Platz will not be sorry. Or not at first. Early on, there is charming, sometimes beautiful documentation of work in the 1970s by the Romanian Sigma group. Inspired by research in bionics and cybernetics, mathematician Lucian Codreanu and his fellows applied scientific method to their observations of the rivers and woods of the Timisoara hunting forest. Doru Tulcan’s abstract sculpture Structuring the Cube makes something surprisingly organic, suggestive of the workings of a crayfish’s eye, from a tiny vocabulary of rods and triangles. Meanwhile, Stefan Bertalan’s Structure of the Elderflower earns its place by virtue of its exquisite draughtsmanship. This being the 1970s, the Sigma group also enjoyed a lot of more-or-less undressed mucking about, and became a focus of dissent against Nicolae Ceausescu’s dictatorship.

The other artists, groups and movements in this show rarely achieved as direct an engagement with the natural world.

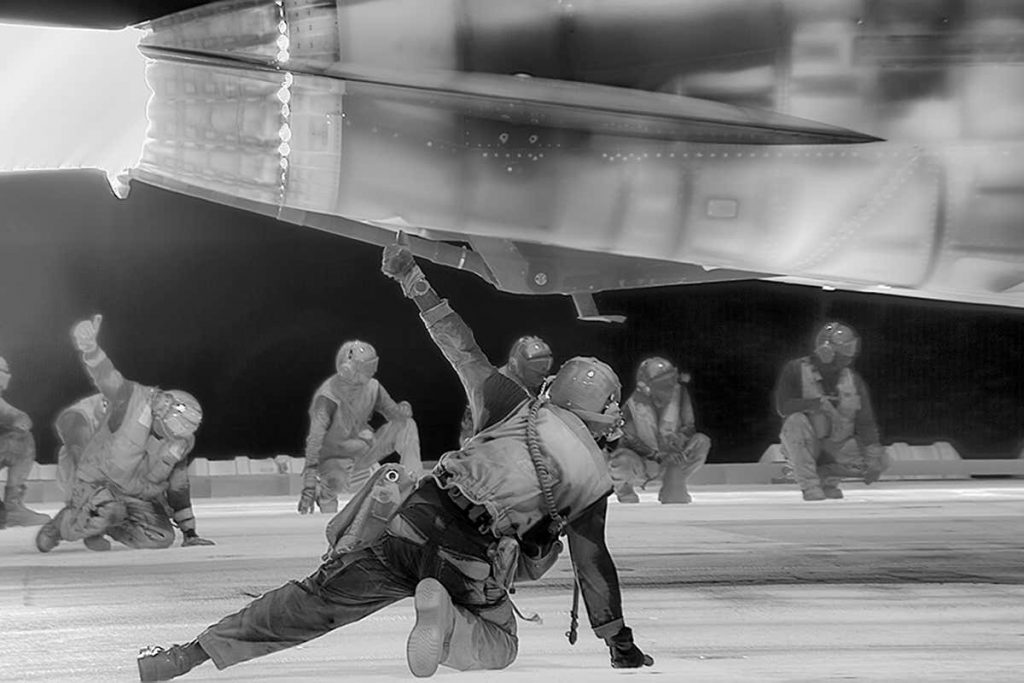

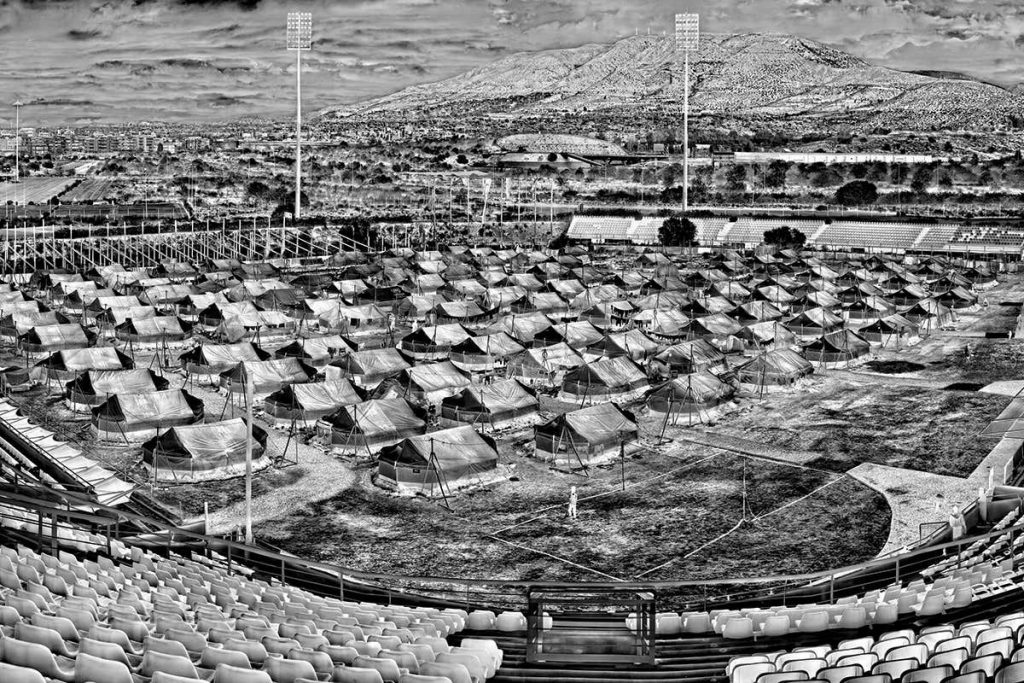

Many pieces here index human activity through changes in the environment. The models and photographs of Anca Benera and Arnold Estefan’s Debrisphere record how landscapes have been altered for military purposes. More often, though, the art focuses on how nature encroaches on human settlement. In Arena, Anri Sala records the decayed state of Tirana zoo, with feral dogs occupying a space meant for people, while the zoo’s “wild” animals languish in cages.

Nature’s eradication of human traces can’t come quickly enough in some cases. In 2003, Polish sculptor Miroslaw Balka visited Auschwitz and filmed deer grazing by the barbed wire fence of the concentration camp. A wall board observes that, in 1942 (when Bambi was released), “while cinemagoers were shedding tears about the emotional story of a little deer, the ‘final solution’ and the murder of millions of people was already being planned”. This is silly: would the world be any better if Bambi’s bereavement left us unmoved?

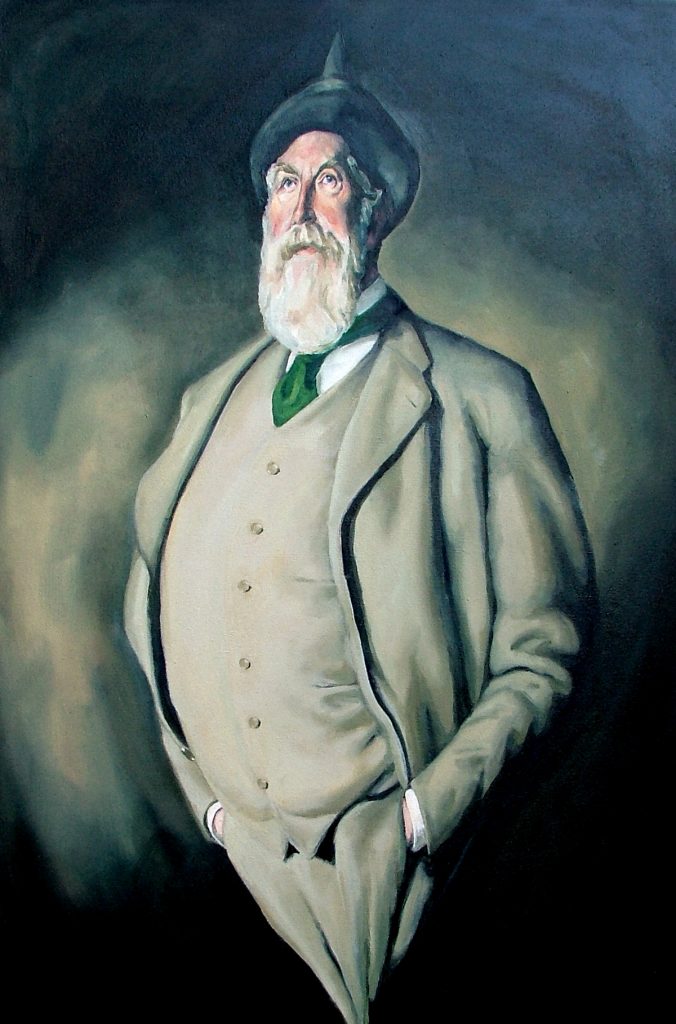

It gets worse. Exquisite allegorical frescoes by 18th-century artist Johann Wenzel Bergl are “recognizable as strategies of absolutist picture propaganda”. And back with Dion: one installation capturing “the lifestyle and self-image of the prototypical ethnographer of colonial times”, isn’t even that, according to the curators, but alludes “to our own imagination of that ethnographer”.

I left feeling rather as Lewis Carroll’s Alice might have felt if, instead of freely stepping through the mirror, she had been shoved through it from behind by a gang of goonish anthropologists.

Natural Histories is a portal into a world where history, politics, horror, guilt and the natural world are sewn together. It is well worth seeing, but I wish the curators had shut up.