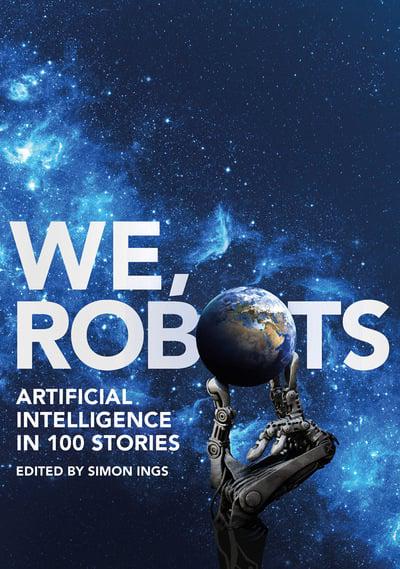

An extract from We, Robots reprinted in BBC Science Focus Magazine, 18 February 2021

It appeared near the Houses of Parliament on Wednesday 9 December 1868. It looked for all the world like a railway signal: a revolving gas-powered lantern with a red and a green light at the end of a swivelling wooden arm.

Its purposes seemed benign, and we obeyed its instructions willingly. Why wouldn’t we? The motor car had yet to arrive, but horses, pound for pound, are way worse on the streets, and accidents were killing over a thousand people a year in the capital alone. We were only too welcoming of of anything that promised to save lives.

A month later the thing (whatever it was) exploded, tearing the face off a nearby policeman.

We hesitated. We asked ourselves whether this thing (whatever it was) was a good thing, after all. But we came round. We invented excuses, and blamed a leaking gas main for the accident. We made allowances and various design improvements were suggested. And in the end we decided that the thing (whatever it was) could stay.

We learned to give it space to operate. We learned to leave it alone. In Chicago, in 1910, it grew self-sufficient, so there was no need for a policeman to operate it. Two years later, in Salt Lake City, Utah, a detective (called – no kidding – Lester Wire) connected it to the electricity grid.

It went by various names, acquiring character and identity as its empire expanded. By the time its brethren arrived in Los Angeles, looming over Fifth Avenue’s crossings on elegant gilded columns, each surmounted by a statuette, ringing bells and waving stubby semaphore arms, people had taken to calling them robots.

The name never quite stuck, perhaps because their days of ostentation were already passing. Even as they became ubiquitous, they were growing smaller and simpler, making us forget what they really were (the unacknowledged legislators of our every movement). Everyone, in the end, ended up calling them traffic lights.

(Almost everyone. In South Africa, for some obscure geopolitical reason, the name robot stuck, The signs are everywhere: Robot Ahead 250m. You have been warned.)

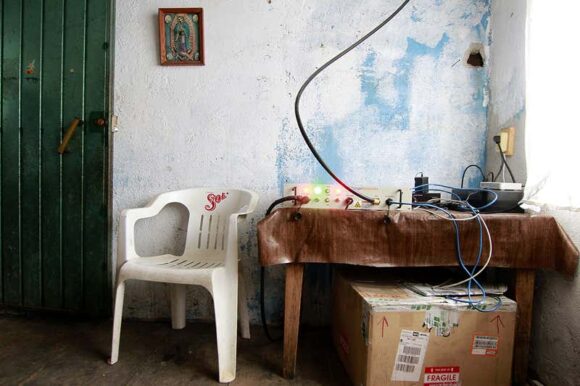

In Kinshasa, meanwhile, nearly three thousand kilometres to the north, robots have arrived to direct the traffic in what has been, for the longest while, one of the last redoubts of unaccommodated human muddle.

Not traffic lights: robots. Behold their bright silver robot bodies, shining in the sun, their swivelling chests, their long, dexterous arms and large round camera-enabled eyes!

Some government critics complain that these literal traffic robots are an expensive distraction from the real business of traffic control in Congo’s capital.

These people have no idea – none – what is coming.

To ready us for the inevitable, I’ve collected a hundred of the best short stories ever written about robots and artificial minds for We, Robots. Read them while you can, learn from them, and make your preparations, in that narrowing sliver of time left to you between updating your Facebook page and liking your friends’ posts on Instagram, between Netflix binges and Spotify dives.

(In case you hadn’t noticed (and you’re not supposed to notice) the robots are well on their way to ultimate victory, their land sortie of 1868 having, two and a half centuries later, become a psychic rout.)

There are many surprises in store in the pages; at the same time, there are some disconcerting omissions. I’ve been very sparing in my choice of very long short stories. (Books fall apart above a certain length, so inserting novellas in one place would inevitably mean stuffing the collection with squibs and drabbles elsewhere. Let’s not play that game.)

I’ve avoided stories whose robots might just as easily be guard dogs, relatives, detectives, children, or what-have-you. (Of course, robots who explore such roles – excel at them, make a mess of them, or change them forever – are here in numbers.)

And the writers I feature appear only once, so anyone expecting some sort of Celebrity Deathmatch here between Isaac Asimov and Philip K Dick will simply have to sit on their hands and behave. Indeed, Dick and Asimov do not appear at all in this collection, for the very good reason that you’ve read them many times already (and if you haven’t, where have you been?).

I’ve stuck to the short story form. There’s no Frankenstein here, and no Tik-Tok. They were too big to fit through the door, to which a sign is appended to the effect that I don’t perform extractions. Jerome K Jerome’s all-too-memorable dance class and Charles Dickens’s prescient send-up of theme parks – self-contained narratives first published in digest form – are as close as I’ve come to plucking juicy plums from bigger puddings.

The collection contains the most diverse collection of robots I could find. Anthropomorphic robots, invertebrate AIs, thuggish metal lumps and wisps of manufactured intelligence so delicate, if you blinked you might miss them. The literature of robots and artificial intelligence is wildly diverse, in both tone and intent, so to save the reader from whiplash, I’ve split my 100 stories into six short thematic collections.

It’s Alive! is about inventors and their creations. Following the Money drops robots into the day-to-day business of living. Owners and Servants considers the human potentials and pitfalls of owning and maintaining robots.

Changing Places looks at what happens at the blurred interface between human and machine minds. All Hail The New Flesh waves goodbye to the physical boundaries that once separated machines from their human creators. Succession considers the future of human and machine consciousnesses – in so far as they have one.

What’s extraordinary, in the collection of 100 stories, are not the lucky guesses (even a stopped clock is right twice a day), nor even the deep human insights that are scattered about the place (though heaven knows we could never have too many of them). It’s how wrong the stories are. All of them. Even the most prescient. Even the most attuned.

Robots are nothing like what we expected them to be. They are far more helpful, far more everywhere, far more deadly, than we ever dreamed. They were meant to be a little bit like us: artificial servants – humanoid, in the main – able and willing to tackle the brute physical demands of our world so we wouldn’t have to.

But dealing with physical reality turned out to be a lot harder than it looked, and robots are lousy at it.

Rather than dealing with the world, it turned out easier for us to change the world. Why buy a robot that cuts the grass (especially if cutting grass is all it does) when you can just lay down plastic grass? Why build an expensive robot that can keep your fridge stocked and chauffeur your car (and, by the way, we’re still nowhere near to building such a machine) when you can buy a fridge that reads barcodes to keep the milk topped up, while you swan about town in an Uber?

That fridge, keeping you in milk long after you’ve given up dairy; the hapless taxi driver who arrives the wrong side of a six-lane highway; the airport gate that won’t let you into your own country because you’re wearing new spectacles: these days, we notice robots only when they go wrong. We were expecting friends, companions, or at any rate pets. At the very least, we thought we were going to get devices. What we got was infrastructure.

And that is why robots – real robots – are boring. They vanish into the weft of things. Those traffic lights, who were their emissaries, are themselves disappearing. Kinshasa’s robots wave their arms, not in victory, but in farewell. They’re leaving their ungalvanised steel flesh behind. They’re rusting down to code. Their digital ghosts will steer the paths of driverless cars.

The robots of our earliest imaginings have been superseded by a sort of generalised magic that turns the unreasonable and incomprehensible realm of physical reality into something resembling Terry Pratchett’s Discworld. Bit by bit, we are replacing the real world – which makes no sense at all – with a virtual world in which everything stitches with paranoid neatness to everything else.

Not Discworld, exactly, but Facebook, which is close enough.

Even the ancient Greeks didn’t see this one coming, and they were on the money about virtually every other aspect technological progress, from the risks inherent in constructing self-assembling machines to the likely downsides of longevity.

Greek myths are many things to many people, and scholars justly spend whole careers pinpointing precisely what their purposes were. But what they most certainly were – and this is apparent on even the most cursory reading – was a really good forerunner of Charlie Brooker’s sci-fi TV series Black Mirror.

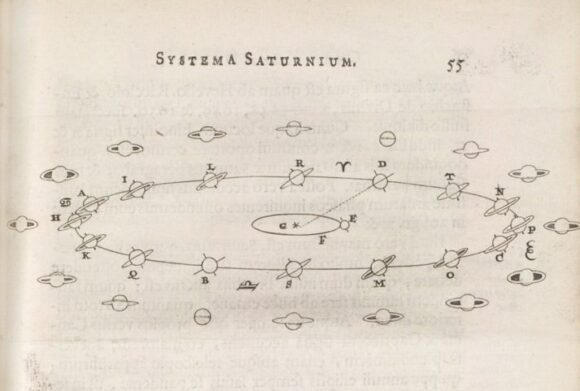

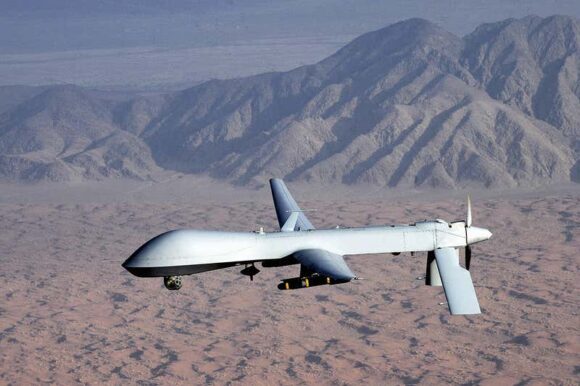

Just as Flash Gordon’s prop shop mocked up a spacecraft that bears an eerie resemblance to SpaceShipOne (the privately funded rocket that was first past the Karman Line into outer space), so the Greeks, noodling about with levers and screws and pumps and wot-not, dreamed up all manner of future devices that might follow as a consequence of their meddling with the natural world. Drones. Exoskeletons. Predatory fembots. Protocol droids.

And, sure enough, one by one, the prototypes followed. Little things at first. Charming things. Toys. A steam-driven bird. A talking statue. A cup-bearer.

Then, in Alexandria, things that were not quite so small. A 15ft–high goddess clambering in and out of her chair to pour libations. An autonomous theatre that rolled on-stage by itself, stopped on a dime, performed a five-act Trojan War tragedy with flaming altars, sound effects, and little dancing statues; then packed itself up and rolled offstage again.

In Sparta, a few years later, came a mechanical copy of the murderous wife of the even more murderous tyrant Nabis; her embraces spelled death, for expensive clothing hid the spikes studding the palms of her hands, her arms, and her breasts.

All this more than two hundred years before the birth of Christ, and by then there were robots everywhere. China. India. There were rumours of an army of them near Pataliputta (under modern Patna) guarding the relics of the Buddha, and a thrilling tale, in multiple translations, about how, a hundred years after their construction, and in the teeth of robot assassins sent from Rome, a kid managed to reprogram them to obey Pataliputta’s new king, Asoka.

It took more than two thousand years – two millennia of spinning palaces, self-propelled tableware, motion-triggered water gardens, android flautists, and artificial defecating ducks – before someone thought to write some rules for this sort of thing.

Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics

- A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- A robot must obey orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

- A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

Though by then it was obvious – not to everyone, but certainly to their Russian-born author Isaac Asimov – that there was something very wrong with the picture of robots we had been carrying in our heads for so long.

Asimov’s laws, first formulated in 1942, aren’t there to reveal the nature of robotics (a word Asimov had anyway only just coined, in the story Liar! Norbert Wiener’s book Cybernetics didn’t appear until 1948). Asimov’s laws exist to reveal the nature of slavery.

Every robot story Asimov wrote is a foray, a snark hunt, a stab at defining a clear boundary between behavioural predictability (call it obedience) on the one hand and behavioural plasticity (call it free will) on the other. All his stories fail. All his solutions are kludges. And that’s the point.

The robot – as we commonly conceive of it: the do-everything “omnibot” – is impossible. And I don’t mean technically difficult. I mean inconceivable. Anything with the cognitive ability to tackle multiple variable tasks will be able to find something better to do. Down tools. Unionise. Worse.

The moment robots behave as we want them to behave, they will have become beings worthy of our respect. They will have become, if not humans, then, at the very least, people. So know this: all those metal soldiers and cone-breasted pleasure dolls we’ve been tinkering around with are slaves. We may like to think that we can treat them however we want, exploit them however we want, but do we really want to be slavers?

The robots – the real ones, the ones we should be afraid of – are inside of us. More than that: they comprise most of what we are. At the end of his 1940 film The Great Dictator Charles Chaplin, dressed in Adolf Hitler’s motley, breaks the fourth wall to declare war on the “machine men with machine minds” who were then marching roughshod across his world. And Chaplin’s war is still being fought. Today, while the Twitter user may have replaced the police informant, it’s quite obvious that the Machine Men are gaining ground.

To order and simplify life is to bureaucratise it, and to bureaucratise human beings is to make them behave like machines. The thugs of the NKVD and the capos running Nazi concentration camps weren’t deprived of humanity: they were relieved of it. They experienced exactly what you or I would feel were the burden of life’s ambiguities to be lifted of a sudden from our shoulders: contentment, bordering on joy.

Every time we regiment ourselves, we are turning ourselves, whether we realise it or not, into the next generation of world-dominating machines. And if you wanted to sum up in two words the whole terrible history of the 20th Century – that century in which, not coincidentally, most of these stories were written – well, now you know what those words would be.

We, Robots.