Visiting Broken Symmetries at FACT, Liverpool for the Financial Times, 30 November 2018

In The Science of Discworld 4: Judgement Day, mathematician Ian Stewart and reproductive biologist Jack Cohen have fun at the expense of the particle-physics community.

Imagine a group of blind sages in a hotel, poking at a foyer piano. After some hours, they arrive at an elegant theory about what a piano is — one that involves sound, frequency, harmony, and the material properties of piano strings.

Then one of their number suggests that they carry the piano upstairs and drop it from the roof. This they do — and spend the rest of the day dreaming up and knocking over countless ugly hypotheses involving hypothetical “twangons” and “thudons” and, oh, I don’t know, “crash bosons”.

The point — that the physicists working at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider in Geneva might be constructing the very quantum reality they were hired to study — is lost on none of the 10,000-odd scientists and engineers involved with the project. And this awareness — that the very idea of science is up for grabs here — may explain why CERN’s scientists have taken so warmly to the artists dropped in their midst.

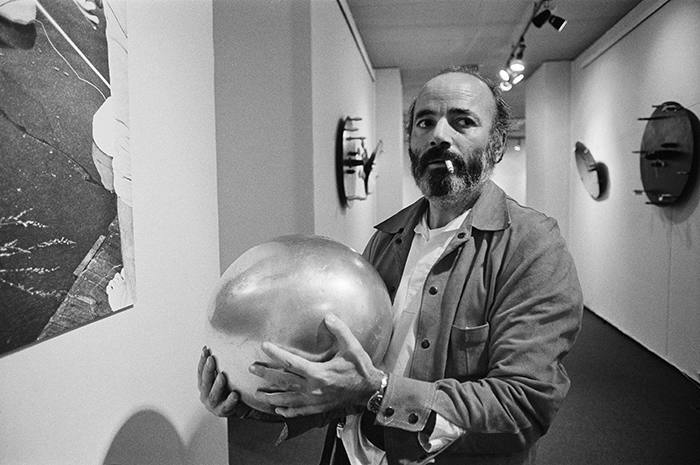

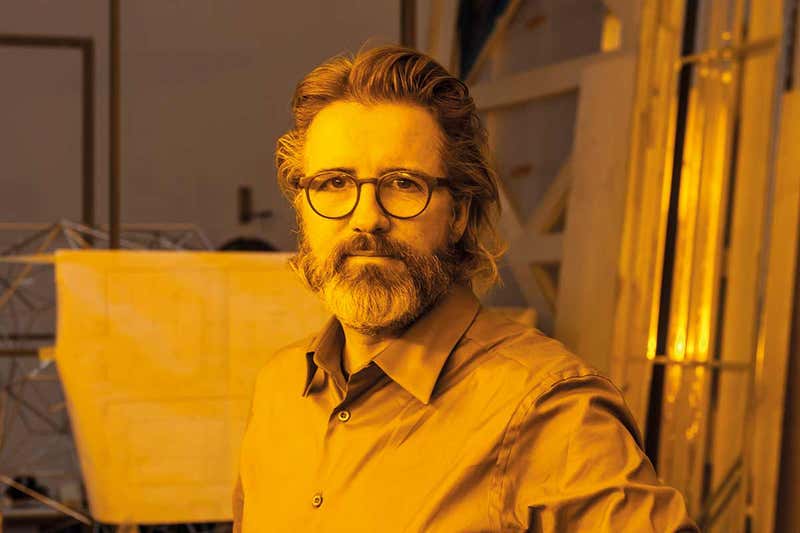

They come on brief visits from the 22 countries that contribute to CERN’s budget. The more established of them — people like Trevor Paglen and Tomás Saraceno — stay for weeks at a time, pursuing some special project. There are joint residencies next year that will see artists shuttling between CERN and astronomical observatories in Chile. Most productive of all are the lucky few chosen for CERN’s Collide International residency programme.

Winning the Collide International gets you two fully funded months in CERN’s labs and labyrinths, rubbing shoulders with arguably the best (and certainly the strangest) minds in physics.

For the exhibition Broken Symmetries at FACT in Liverpool, Arts at CERN director Monica Bello and Peruvian scientist and curator Jose Carlos Mariategui have commissioned new work by CERN’s recent residents, runners-up and honorable mentions. It’s a celebration of CERN’s three-year curatorial collaboration with FACT, the Foundation for Art and Creative Design. Next April the show moves to CCCB , the Centre for Contemporary Culture in Barcelona, where it will effectively advertise CERN’s next three-year partnership, with Barcelona’s city council.

From there, Broken Symmetries travels to Le Lieu Unique in Nantes, France and iMAL, the centre for digital cultures and technology in Sint-Jans-Molenbeek, Belgium, where it finally shuts up shop in the summer of 2020. All this travelling has a point. Since the end of the nineteenth century, physics has been — out of intellectual and financial necessity — an international institution.

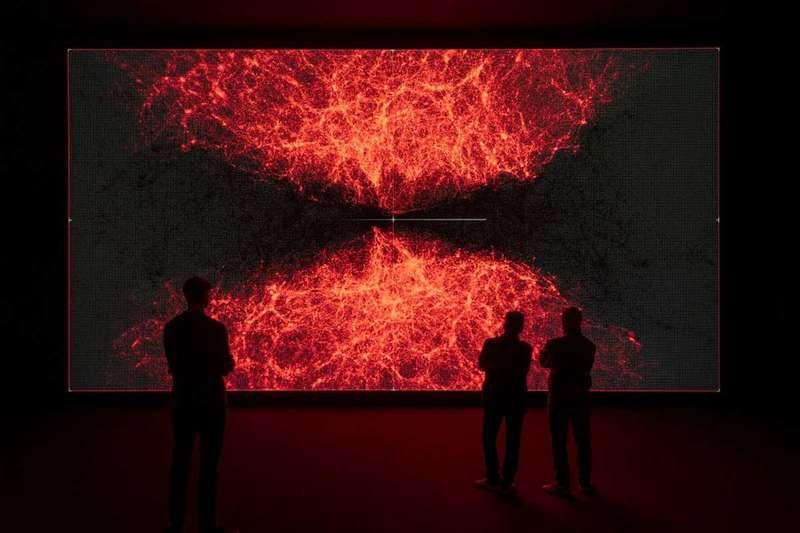

So there is a nice double-meaning to the title of the video made for this show by Ruth Jarman and Joe Gerhardt, who work under the name Semiconductor. The View from Nowhere refers to the scientific ideal of objective observation. But by echoing PM Theresa May’s notorious “citizens of nowhere” jibe, it just as effectively trumpets the rootless cosmopolitanism of the scientific community.

The video itself is almost pure anthropology, as the pair explore why it is that people working on the same project explain what they’re doing in so many different ways. Language is full of traps. The hidden world of particles can only be conceptualised by analogies and metaphors, which themselves are limited or misleading. The visual stylings of artists are just as unreliable, of course, but at least they supplement the vocabulary available to researchers. This is one of the possibilities that excites the architect of the residency programme, Monica Bello: “Since I began, it has been very important to me to bring artworks and experiences to the scientific community. This,” she points out, “is an audience in itself.”

Some art here addresses its patrons directly, in the eighteenth-century manner. Through narrative, memoir and archive, Taiwan-born Londoner Yu-Chen Wang explores the human scale of the CERN project. Her video installation We aren’t able to prove that just yet, but we know it’s out there seeks to acknowledge CERN’s unsung multitudes: its technicians, analysts and engineers.

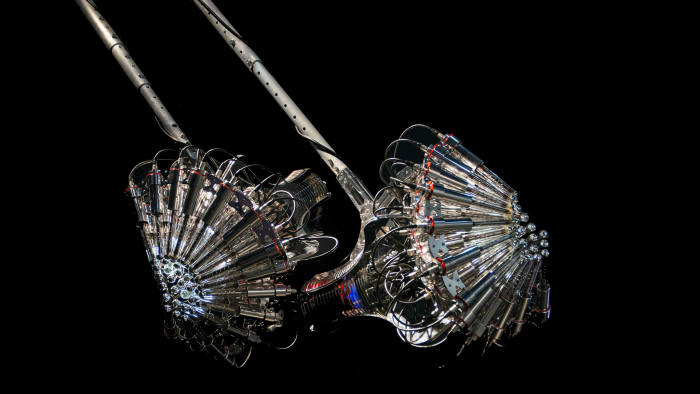

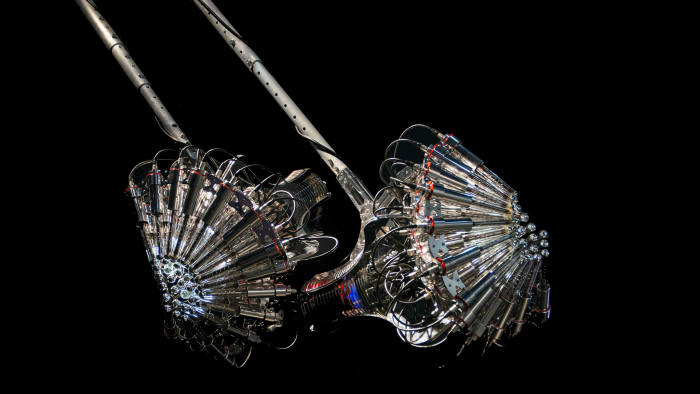

South Korean artist Yunchul Kim reveals the aesthetic elements of his patrons’ work. His sketchbooks, recently on show at the Korean Cultural Centre in London, stripped the components of the Large Hadron Collider (almost all hand-turned — there’s nothing mass-produced about the LHC) down to their design elements. Here, with a three-part sculpture called Cascade, Kim fashions a mechanism that, in homage to the LHC, makes sub-atomic activities visible. Each time a cosmic particle hits his handmade detector, a signal is sent to a gigantic chandelier-like structure. This, in response, pumps a clear, viscous liquid through countless narrow capillary tubes which trail across the floor of the gallery and up into swooping tubes of clear Perspex. Because the refractive index of the capillaries matches the refractive index of the Perspex, the capillaries vanish inside the tubes, leaving beads of liquid apparently suspended in mid-air, rather as one might imagine particles suspended in the magnetic ring of CERN’s collider.

Visitors to CERN run the risk of being inundated by information, and some artists here have saved themselves from drowning by clutching at esoteric straws. Works like Lea Porsager’s Cosmic Strike (a concoction of 3D-animated strings and a neutrino horn from the LHC stores) and Haroon Mirza and Jack Jelfs’s one1one — a bopping 100bpm disco floor drawing on incantation, ritual, and the relationship between written and spoken word — are not the betrayals of hard science they might at first seem. Physics at this extreme tips into metaphysics very easily, witness the ongoing arguments over whether elegant but untestable string theories count as science at all.

Diann Bauer’s Scalar Oscillation, a collaboration with the sound artist Seth Ayyaz, tackles the science head-on. How are we to encapsulate, in painting or poetry or any human medium, the scalar richness of the world, which is so much bigger than we are and so much more intricate than we can possibly perceive? A single sound shrinks to a click, then expands to reveal the oceanic reverberations hidden at its heart. Clean-edged, constructivist visuals try, and fail, to reduce the world to a single sign. Suzanne Treister takes an even more literal approach with The Holographic Universe Theory of Art History, which treats images like particles in an accelerator, projecting over 25,000 pictures from art history (from cave paintings to contemporary art) at 25 frames per second in a looped sequence.

James Bridle’s State of Sin simply offers the scientists of CERN something they can use: random numbers. A family of goofy tripods gathers numbers from the gallery environment: the temperature of the air, the airflow generated by a desk fan, from sounds in the gallery and from fluctuations in the light spilling from a neon tube. Bridle’s point being, CERN’s complex computations require a constant supply of random numbers, and such true randomness cannot be computed, but must be fetched from the messiness of the world.

How many visitors will “get” Bridle’s work? How many, resting their chins on the frame of Juan Cortes’s ingenious clockwork galaxy Supralunar, will realise that the sounds shivering through their jawbones are drawn in real time from the movements of optic fibres inside the clockwork, and that they echo with surprising accuracy the patterns in astronomical data from which scientists have inferred the existence of dark matter? The answer to such boorish questions has traditionally been, “You get out of art what you bring to it, so it doesn’t matter.”

But with this sort of art, I think it does matter. Art that derives from other cultural production must always contend with a creeping sense of its own bankruptcy. Pop art succeeded in making art out of pre-existing media because it flaunted that bankruptcy, chose mass media, and was prepared to laugh at itself.

The art of Broken Symmetries, on the other hand, feeds off highly abstruse media — off bubble-chamber drawings and statistical analyses, all of them generated in pursuit of one fixed and timeless standard cosmological model. This art can’t but struggle to find a purchase in a world full of (indeed, glutted with) other, more familiar, more lively aesthetic vocabularies.

My uneasy feeling is that the artists have done rather too good a job of pointing up the existential implausibility of the whole enterprise. I was reminded of John Gardner’s short, savage novel Grendel, which tells the Beowulf legend from the monster’s point of view.

“They only think they think,” grumbles Grendel, who has the measure of both our intellect and our vanity. “No total vision, total system, merely schemes with a vague family resemblance, no more identity than bridges and, say, spider-webs. But they rush across chasms on spider-webs, and sometimes they make it, and that, they think, settles that!”