For New Scientist, 1 February 2017

In a small, windowless corner of the University of Dundee, UK, Caroline Erolin of the Centre for Anatomy & Human Identification is ironing a fossilised pterodactyl.

At least, that’s what she appears to be doing. In fact, Erolin’s “iron” is a handheld 3D scanner, and her digitised animals are now being used as teaching aids worldwide. Her enthusiasm for the work (which she has to squeeze between research into medical visualisation and haptics) is palpable. She is not just bringing animals back from the dead, but helping to bring a great collection back to life.

In 1884, the biologist and classicist D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson began assembling a teaching and research museum in Dundee. An energetic philanthropist and a natural diplomat, Thompson had a broad network of friends and contacts – among them members of Dundee’s own whaling community, who provided him with extraordinary, then-unique specimens of Arctic fauna.

In 1956, the building that housed the University of Dundee’s natural history department was scheduled for demolition and Thompson’s collection, created as part of his work there, was dispersed. Scholars have been scrambling to recover its treasures ever since. Asked whether it can in fact be reassembled, Erolin laughs and gestures at the confines in which the surviving items are (rather artfully) squeezed. “It’s a question of space. We’re already sitting on an entire elephant skeleton. Where on earth would we put that?”

ADVERTISING

inRead invented by Teads

It’s largely not a genuine problem though, in part because advances in digitisation are changing the priorities of collections worldwide. Even more importantly, it is generally acknowledged that Thompson has outgrown Dundee: he belongs to the world. Together with Charles Darwin, Thompson, who died in 1948, is the most culturally influential English-speaking biologist in history.

We have one book to thank for that: On Growth and Form, first published in 1917 – an event commemorated by an exhibition, A Sketch of the Universe: Art, science and the influence of D’Arcy Thompson, at the Edinburgh City Art Centre.

“Thompson described his landmark book as all preface”

In neither the first edition nor the revised and expanded 1942 version does Thompson talk much about Darwin, and even in the 1940s he considered genetics hardly more than a distraction. Thompson was pursuing an entirely different line: the way in which physical constraints and the initial conditions of life shape the development of plants and animals.

Thompson was fascinated by tiny, single-celled shelled organisms such as foraminifera and radiolaria. He was convinced (rightly) that their wildly diverse shell shapes play no evolutionary role: they arise at random, their beauty emerging from the self-organising properties of matter, not from any biological code.

Even as geneticists like Ernst Mayr and Theodosius Dobzhansky were revealing the genetic mechanisms that constrain how living things evolve, Thompson was revealing the constraints and opportunities afforded to living things by physics and chemistry. Crudely put, genetics explains why dogs, say, look like other dogs. Thompson did something different: he glimpsed why dogs look the way they do.

Most of Thompson’s contemporaries were caught up in a genetic revolution, synthesising the seemingly incompatible demands of chromosomal genetics and Darwinian selection theory. No one ever seriously doubted Thompson’s importance – his book has always been a classic text – but at the same time, few have ever quite known what to do with him.

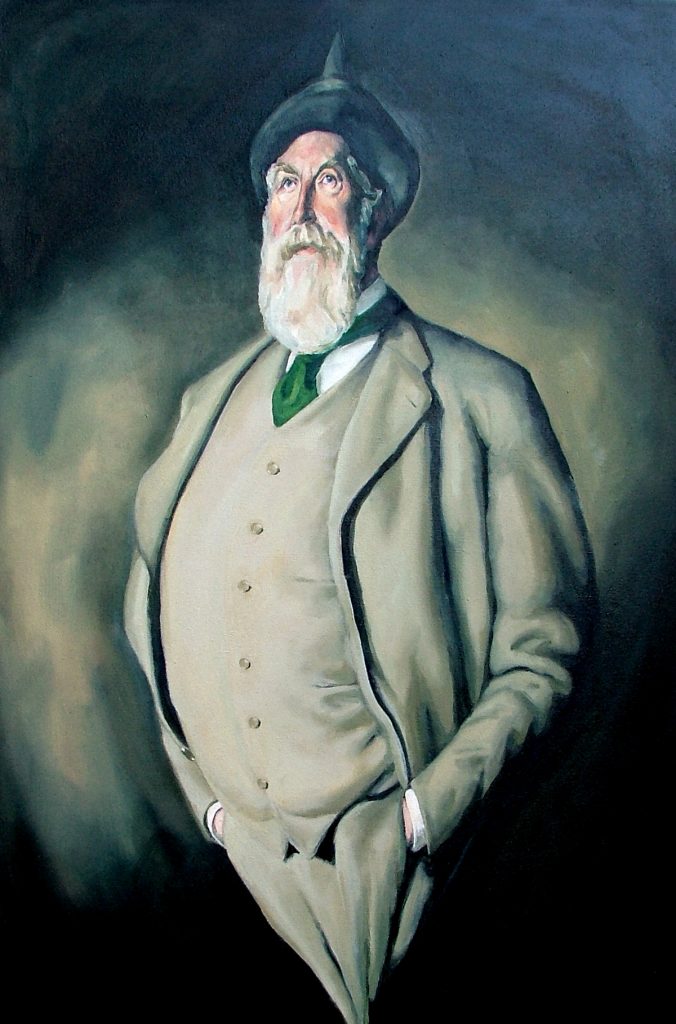

Portrait of D'Arcy Thompson by Darren McFarlane

Darren McFarlane, Scarus, Pomacanthus, 2012, oil on canvas. (University of Dundee Museum Services © the artist)

Thompson himself (pictured above as morphed by artist Darren McFarlane) understood the problem; he described his landmark book as “all preface”: the sketch of a territory he lacked the mathematical skill to penetrate. What the arguments in On Growth and Form really needed is a computer, and a big one at that (which makes Thompson a character who might have dropped straight out of the pages of Tom Stoppard’s play Arcadia).

Artists, on the other hand, from Henry Moore to Richard Hamilton to Eduardo Paolozzi, knew exactly what to do – and the Edinburgh exhibition combines the University of Dundee’s own collection of biomorphic, Thompsonesque art with new commissions. Several stand-out pieces are by artists who were students at Dundee’s own Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design.

To its credit, Thompson’s alma mater has not been slow to exploit the way his meticulous and beautiful work straddles art and science: it supports a dedicated art-science crossover gallery called LifeSpace, as well as offering degrees in animation, medical art and medical imaging, connecting digital processes with traditional illustration. They are making the most of On Growth and Form‘s centenary, but the influence of Thompson on the university is deep and abiding.

That is as well. For all our anxious predictions about genetic engineering, for all the hype surrounding synthetic biology, and all the many hundreds of graduate design shows stuffed with “imaginary animals”, we have barely begun to explore let alone exploit the spaces Thompson’s vision revealed to us.

Read more: https://www.newscientist.com/article/2120057-darcy-wentworth-thompson-the-man-who-shaped-biology-and-art/#ixzz63gNDj1gc