An essay on the machineries of science-fiction film, originally written for the BFI

Science fiction is about escape, about transcendence, about how, with the judicious application of technology, we might escape the bounds of time, space and the body.

Science fiction is not at all naive, and almost all of it is about why the dream fails: why the machine goes wrong, or works towards an unforeseen (sometimes catastrophic) end. More often than not science fiction enters clad in the motley of costume drama – so polished, so chromed, so complete. But there’s always a twist, a tear, a weak seam.

Science fiction takes what in other movies would be the set dressing, finery from the prop shop, and turns it into something vital: a god, a golem, a puzzle, a prison. In science fiction, it matters where you are, and how you dress, what you walk on and even what you breathe. All this stuff is contingent, you see. It slips about. It bites.

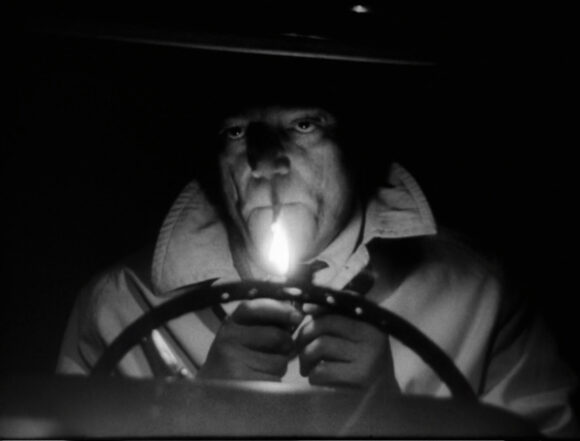

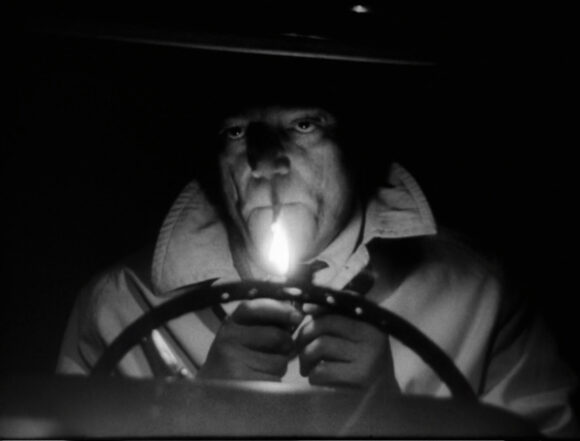

Sometimes, in this game of “It’s behind you!” less is more. Futuristic secret agent Lemmy Caution explores the streets of the distant space city Alphaville (1965) and the strangeness is all in Jean-Luc Godard’s cut, his dialogue, and the sharpest of sharp scripts. Alphaville, you see (only you don’t; you never do) is nothing more than a rhetorical veil cast over contemporary Paris.

More usually, you’ll grab whatever’s to hand: tinsel and Pan Stick and old gorilla costumes. Two years old by 1965, at least by Earth’s reckoning, William Hartnell’s Doctor was tearing up the set, and would, in other bodies and other voices, go on tearing up, tearing down and tearing through his fans’ expectations for the next 24 years, production values be damned. Bigger than its machinery, bigger even than its protagonist, Doctor Who (1963) was, in that first, long outing, never in any sense realistic, and that was its strength. You never knew where you’d end up next: a comedy, a horror flick, a Western-style showdown. The Doctor’s sonic screwdriver was the point: it said, We’re making this up as we go along.

So how did it all get going? Much as every other kind of film drama got going: with a woman in a tight dress. It is 1924: in a constructivist get- up that could spring from no other era, Aelita, Queen of Mars (actress and film director Yuliya Solntseva) peers into a truly otherworldly crystalline telescope and spies Earth, revolution, and Engineer Los. And Los, on being observed, begins to dream of her.

You’d think, from where we are now, deluged in testosterone from franchises like Transformers and Terminators, that such romantic comedy beginnings were an accident of science fiction’s history: a charming one-off. They’re not. They’re systemic. Thea von Harbou wrote novels about to-die-for women and her husband Fritz Lang placed them at the helm of science fiction movies like Metropolis (1927) and Frau im Mond (1929). The following year saw New York given a 1980s makeover in David Butler’s musical comedy Just Imagine. “In 1980 – people have serial numbers, not names,” explained Photoplay; “marriages are all arranged by the courts… Prohibition is still an issue… Men’s clothes have but one pocket. That’s on the hip… but there’s still love! ” (Griffith, 1972) Just Imagine boasted the most intricate setting ever created for a movie. 205 engineers and craftsmen took five months over an Oscar-nominated build costing $168,000. You still think this film is marginal? Just Imagine’s weird guns and weirder spaceships ended up reused in the serial Flash Gordon (1936).

How did we get from musical comedy to Keanu Reeves’s millennial Neo shopping in a virtual firearms mall? Well, by rocket, obviously. Science fiction got going just as our fascination with future machinery overtook our fascination with future fashion. Lang wanted a real rocket launch for the premiere of Frau im Mond and roped in no less a physicist than Hermann Oberth to build it for him. When his 1.8-metre tall liquid- propellant rocket came to nought, Oberth set about building one eleven metres tall powered by liquid oxygen. They were going to launch it from the roof of the cinema. Luckily they ran out of money.

What hostile critics say is true: for a while, science fiction did become more about the machines than about the people. This was a necessary excursion, and an entertaining one: to explore the technocratic future ushered in by the New York World’s Fair of 1939–1940 and realised, one countdown after another, in the world war and cold war to come. (Science fiction is always, ultimately, about the present.) HG Wells wrote the script for Things to Come (1936). Destination Moon (1950) picked the brains of sf writer Robert Heinlein, who’d spent part of the war designing high-altitude pressure suits, to create a preternaturally accurate forecast of the first manned mission to the moon. George Pal’s Conquest of Space, five years later, based its technology on writings and designs in Collier’s Magazine by former Nazi rocket designer Wernher von Braun. In the same year, episode 20 of the first season of Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Colour was titled Man in Space and featured narration from Braun and his close (anti-Nazi) friend and colleague Willy Ley.

Another voice from that show, TV announcer Dick Tufeld, cropped up a few years later as voice of the robot in the hit 1965 series Lost in Space, by which time science fiction could afford to calm down, take in the scenery, and even crack a smile or two. The technocratic ideal might seem sterile now, but its promise was compelling: that we’d all live lives of ease and happiness in space, the Moon or Mars, watched over by loving machines: the Robinson family’s stalwart Robot B–9, perhaps. Once clear of the frontier, there would be few enough places for danger to lurk, though if push came to shove, the Tracy family’s spectacular Thunderbirds (1965) were sure to come and save the day. Star Trek’s pleasant suburban utopias, defended in extremis by phasers that stun more than kill, are made, for all their scale and spread, no more than village neighbourhoods thanks to the magic of personal teleportation, and all are webbed into one gentle polis by tricorders so unbelievably handy and capable, it took our best minds half a century to build them for real.

Once the danger’s over though, and the sirens are silenced -– once heaven on earth (and elsewhere) is truly established – then we hit a quite sizeable snag. Gene Roddenberry was right to have pitched Star Trek to Desilu Studios as “Wagon Train to the stars”, for as Dennis Sisterson’s charming silent parody Steam Trek: the Moving Picture (1994) demonstrates, the moment you reach California, the technology that got you there loses its specialness. The day your show’s props become merely props, is the day you’re not making science fiction any more. Forget the teleport, that rappelling rope will do. Never mind the scanner: just point.

Realism can only carry you so far. Pavel Klushantsev’s grandiloquent model-making and innovative special effects – effects that Kubrick had to discover for himself over a decade later for 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) – put children on The Moon (1965) and ballet dancers on satellite TVs (I mean TV sets on board satellites) in Road to the Stars (1957). Such humane and intelligent gestures can only accelerate the exhaustion of “realistic” SF. You feel that exhaustion in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Indeed, the boredom and incipient madness that haunt Keir Dullea and poor, boxed-in HAL on board Discovery One are the film’s chief point: that we cannot live by reason alone. We need something more.

The trouble with Utopias is they stay still, and humanity is nothing if not restless. Two decades earlier, the formal, urban costume stylings of Gattaca (1997) and The Matrix (1999) would have appeared aspirational. In context, they’re a sign of our heroes’ imprisonment in conformist plenty.

What is this “more” we’re after, then, if reason’s not enough? At very least a light show. Ideally, redemption. Miracles. Grace. Most big- budget movies cast their alien technology as magic. Forbidden Planet (1956) owes its plot to The Tempest, spellbinding audiences with outscale animations and meticulous, hand-painted fiends from the id. The altogether more friendly water probe in James Cameron’s The Abyss took hardly less work: eight months’ team effort for 75 seconds of screen time.

Arthur Clarke, co-writer on 2001 once said: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” He was half right. What’s missing from his formulation is this: sufficiently advanced technology can also resemble nature – the ordinary weave and heft of life. Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris (1972) and Stalker (1979) both conjure up alien presences out of forests and bare plastered rooms. Imagine how advanced their technology must be to look so ordinary!

In Alien (1979) Salvador Dali’s friend H R Giger captured this process, this vanishing into the real, half-done. Where that cadaverous Space Jockey leaves off and its ship begins is anyone’s guess. Shane Carruth’s Upstream Color (2013) adds the dimension of time to this disturbing mix, putting hapless strangers in the way of an alien lifeform that’s having to bolt together its own lifecycle day by day in greenhouses and shack laboratories.

Prometheus (2012), though late to the party, serves as an unlovely emblem to this kind of story. Its pot of black goo is pure Harry Potter: magic in a jar. Once cast upon the waters, though, it’s life itself, in all its guile and terror.

Where we have trouble spotting what’s alive and what’s not – well, that’s the most fertile territory of all. Welcome to Uncanny Valley. Population: virtually everyone in contemporary science fiction cinema. Westworld (1973) and The Stepford Wives (1975) broke the first sod, and their uncanny children have never dropped far from the tree. In the opening credits of a retrodden Battlestar Galactica (2004), Number Six sways into shot, leans over a smitten human, and utters perhaps the most devastating line in all science fiction drama: “Are you alive?” Whatever else Number Six is (actress Tricia Helfer, busting her gut to create the most devasting female robot since Brigitte Helm in Metropolis), alive she most certainly is not.

The filmmaker David Cronenberg is a regular visitor to the Valley. For twenty years, from The Brood (1979) to eXistenZ (1999), he showed us how attempts to regulate the body like a machine, while personalising technology to the point where it is wearable, can only end in elegaic and deeply melancholy body horror. Cronenberg’s visceral set dressings are one of a kind, but his wider, philosophical point crops up everywhere – even in pre-watershed confections like The Six Million Dollar Man (1974–1978) and The Bionic Woman (1976–1978), whose malfunctioning (or hyperfunctioning) bionics repeatedly confronted Steve and Jaime with the need to remember what it is to be human.

Why stay human at all, if technology promises More? In René Laloux’s Fantastic Planet (1973) the gigantic Draags lead abstract and esoteric lives, astrally projecting their consciousnesses onto distant planets to pursue strange nuptials with visiting aliens. In Pi (1998) and Requiem for a Dream (2000), Darren Aronofsky charts the epic comedown of characters who, through the somewhat injudicious application of technology, have glimpsed their own posthuman possibilities.

But this sort of technologically enabled yearning doesn’t have to end badly. There’s bawdy to be had in the miscegenation of the human and the mechanical, as when in Sleeper (1973), Miles Monroe (Woody Allen) wanders haplessly into an orgasmatron, and a 1968-vintage Barbarella (Jane Fonda) causes the evil Dr Durand-Durand’s “Excessive Machine” to explode.

For all the risks, it may be that there’s an accommodation to be made one day between the humans and the machinery. Sam Bell’s mechanical companion in Moon (2009), voiced by Kevin Spacey, may sound like 2001’s malignant HAL, but it proves more than kind in the end. In Spike Jonze’s Her (2013), Theodore’s love for his phone’s new operating system acquires a surprising depth and sincerity – not least since everyone else in the movie seems permanently latched to their smartphone screen.

“… But there’s still love!” cried Photoplay, more than eighty years ago, and Photoplay is always right. It may be that science fiction cinema will rediscover its romantic roots. (Myself, I hope so.) But it may just as easily take some other direction completely. Or disappear as a genre altogether, rather as Tarkovsky’s alien technology has melted into the spoiled landscapes of Stalker. The writer and aviator Antoine de Saint- Exupery, drunk on his airborne adventures, hit the nail on the head: “The machine does not isolate man from the great problems of nature but plunges him more deeply into them.”

You think everything is science fiction now? Just you wait.