Reading Sidarta Ribeiro’s The Oracle of Night: The History and Science of Dreams for the Times, 2 January 2022

Early in January 1995 Sidarta Ribeiro, a Brazilian student of neuroscience, arrived in New York City to study for his doctorate at Rockefeller University. He rushed enthusiastically into his first meeting — only to discover he could not understand a word people were saying. He had, in that minute, completely forgotten the English language.

It did not return. He would turn up for work, struggle to make sense of what was going on, and wake up, hours later, on his supervisor’s couch. The colder and snowier the season became, the more impossible life got until, “when February came around, in the deep silence of the snow, I gave in completely and was swallowed up into the world of Morpheus.”

Ribeiro struggled into lectures so he didn’t get kicked out; otherwise he spent the entire winter in bed, sleeping; dozing; above all, dreaming.

April brought a sudden and extraordinary recovery. Ribeiro woke up understanding English again, and found he could speak it more fluently than ever before. He befriended colleagues easily, drove research, and, in time, announced the first molecular evidence of Freud’s “day residue” hypothesis, in which dreams exist to process memories of the previous day.

Ribeiro’s rich dream life that winter convinced him that it was the dreams themselves — and not just the napping — that had wrought a cognitive transformation in him. Yet dreams, it turned out, had fallen almost entirely off the scientific radar.

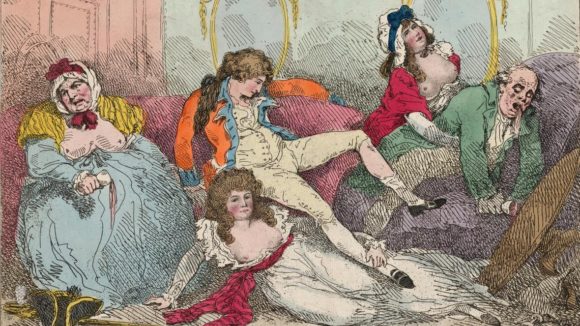

The last dream researcher to enter public consciousness was probably Sigmund Freud. Freud at least seemed to draw coherent meaning from dreams — dreams that had been focused to a fine point by fin de siecle Vienna’s intense milieu of sexual repression.

But Freud’s “royal road to the unconscious” has been eroded since by a revolution in our style of living. Our great-grandparents could remember a world without artificial light. Now we play on our phones until bedtime, then get up early, already focused on a day that is, when push comes to shove, more or less identical to yesterday. We neither plan our days before we sleep, nor do we interrogate our dreams when we wake. It it any wonder, then, that our dreams are no longer able to inspire us? When US philosopher Owen Flanagan says that “dreams are the spandrels of sleep”, he speaks for almost all of us.

Ribeiro’s distillation of his life’s work offers a fascinating corrective to this reductionist view. His experiments have made Freudian dream analysis and other elements of psychoanalytic theory definitively testable for the first time — and the results are astonishing. There is material evidence, now, for the connection Freud made between dreaming and desire: both involve the selective release of the brain chemical dopamine.

The middle chapters of The Oracle of Night focus on the neuroscience, capturing, with rare candour, all the frustrations, controversies, alliances, ambiguities and accidents that make up a working scientists’ life.

To study dreams, Ribeiro explains, is to study memories: how they are received in the hippocampus, then migrate out through surrounding cortical tissue, “burrowing further and further in as life goes on, ever more extensive and resistant to disturbances”. This is why some memories can survive, even for more than a hundred years, in a brain radically altered by the years.

Ribeiro is an excellent communicator of detail, and this is important, given the size and significance of his claims. “At their best,” he writes, “dreams are the actual source of our future. The unconscious is the sum of all our memories and of all their possible combinations. It comprises, therefore, much more than what we have been — it comprises all that we can be.”

To make such a large statement stick, Ribeiro is going to need more than laboratory evidence, and so his scientific account is generously bookended with well-evidenced anthropological and archaeological speculation. Dinosaurs enjoyed REM sleep, apparently — a delightfully fiendish piece of deduction. And was the Bronze Age Collapse, around 1200 BC, triggered by a qualitative shift how we interpreted dreams?

These are sizeable bread slices around an already generous Christmas-lunch sandwich. On page 114, when Ribeiro declares that “determining a point of departure for sleep requires that we go back 4.5 billion years and imagine the conditions in which the first self-replicating molecules appeared,” the poor reader’s heart may quail and their courage falter.

A more serious obstacle — and one quite out of Ribeiro’s control — is that friend (we all have one) who, feet up on the couch and both hands wrapped around the tea, baffs on about what their dreams are telling them. How do you talk about a phenomenon that’s become the sinecure of people one would happily emigrate to avoid?

And yet, by taking dreams seriously, Bibeiro must also talk seriously about shamanism, oracles, prediction and mysticism. This is only reasonable, if you think about it: dreams were the source of shamanism (one of humanity’s first social specialisations), and shamanism in its turn gave us medicine, philosophy and religion.

When lives were socially simple and threats immediate, the relevance of dreams was not just apparent; it was impelling. Even a stopped watch is correct twice a day. With a limited palette of dream materials to draw from, was it really so surprising that Rome’s first emperor Augustus found his rise to power predicted by dreams — at least according to his biographer Suetonius? “By simulating objects of desire and aversion,” Ribeiro argues, “the dream occasionally came to represent what would in fact happen”.

Growing social complexity enriches dream life, but it also fragments it (which may explain all those complaints that the gods have fallen silent, which we find in texts dated between 1200 to 800 BC). The dreams typical of our time, says Ribeiro, are “a blend of meanings, a kaleidoscope of wants, fragmented by the multiplicity of desires of our age”.

The trouble with a book of this size and scale is that the reader, feeling somewhat punch-drunk, can’t help but wish that two or three better books had been spun from the same material. Why naps are good for us, why sleep improves our creativity, how we handle grief — these are instrumentalist concerns that might, under separate covers, have greatly entertained us. In the end, though, I reckon Ribeiro made the right choice. Such books give us narrow, discrete glimpses into the power of dreams, but leave us ignorant of their real nature. Ribeiro’s brick of a book shatters our complacency entirely, and for good.

Dreaming is a kind of thinking. Treating dreams as spandrels — as so much psychic “junk code” — is not only culturally illiterate — it runs against everything current science is telling us. You are a dreaming animal, says Ribeiro, for whom “dreams are like stars: they are always there, but we can only see them at night”.

Keep a dream diary, Ribeiro insists. So I did. And as I write this, a fortnight on, I am living an extra life.