As I write, President Donald Trump has just accused former incumbent Barack Obama of having tapped his campaign phones during the 2016 election season. I doubt very much whether this will be a major issue by the time these words are read. Most likely it’ll have been overtaken by “FAKED” nuclear exchanges over the South China Sea.

Kleptocracy moves faster than ordinary politics. Across the media, opinion writers are having to learn how to think like crime reporters. It’s frightening, but undeniably exhilarating.

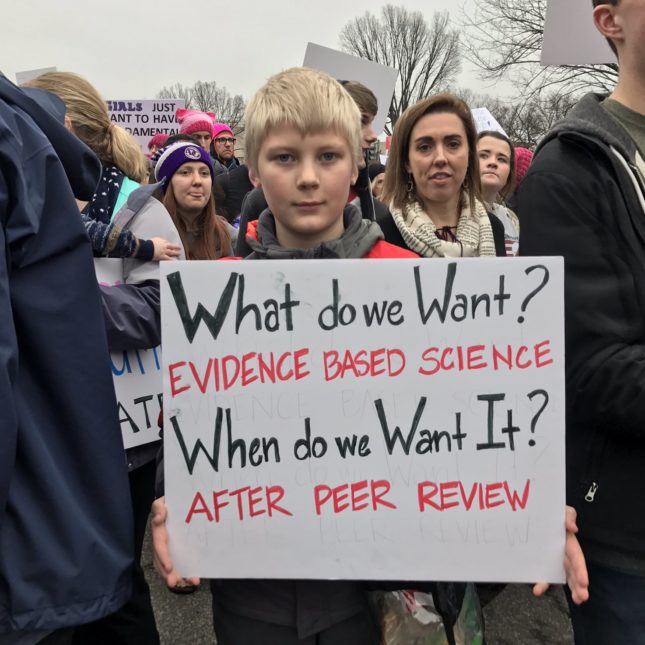

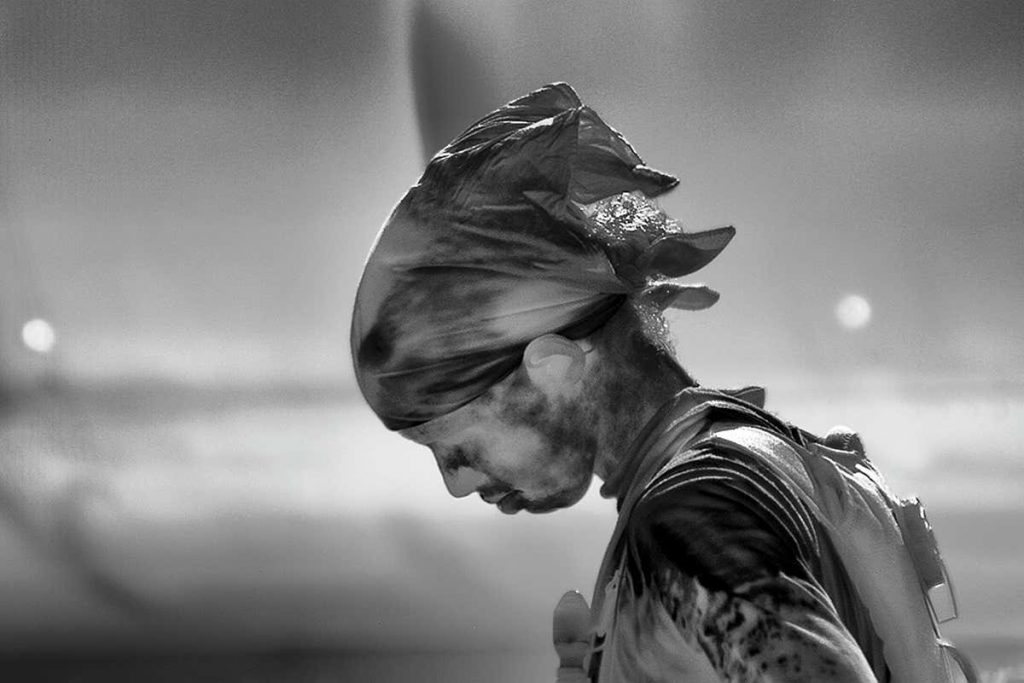

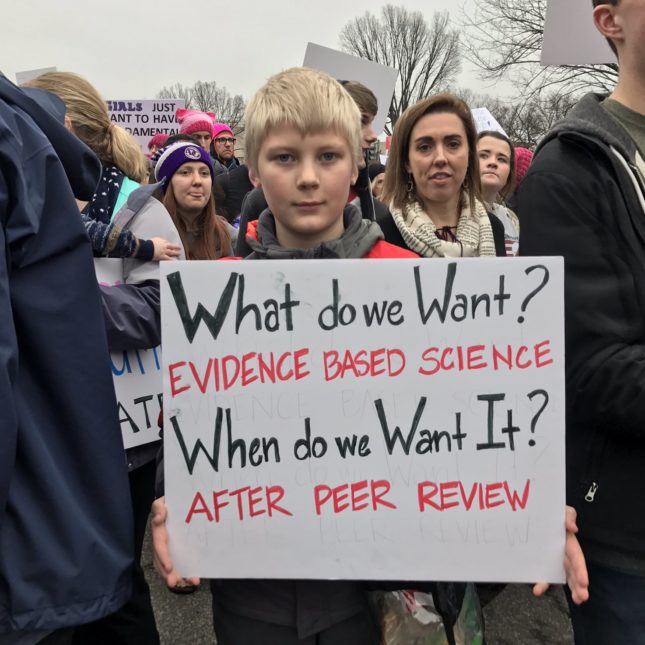

Old forms of civic engagement seem hardly relevant now. On April 22, scientists will gather across the world to protest the Trump administration’s de facto dismantling of the EPA, veiled threats directed at programs of vaccination, cuts in NASA’s climate-studies funding, and any number of other depredations. All very noble, to protest this outrage, and necessary in its way. But the rest of us might just as easily marvel at the alacrity and efficiency with which groups of suddenly vulnerable people round themselves up. The spectacle of well-educated people congratulating themselves on their effortless (because sacrifice-free) “intersectionality”, while at the same time complaining about their job security, is unlikely to prove particularly edifying, least of all since the “cosmopolitanism” so necessary to science (I mean devotion to an idea or ideas bigger than the nation state) is rapidly becoming synonymous with disloyalty.

The March for Science was conceived on a Reddit forum as recently as 20 January, yet we already find ourselves operating at an entirely different level of discourse. Science illumines small, detailed corners of the world, but it’s the entire reality of that world that’s under threat now. We are dealing with an administration that, when not lost in the toils of its own mythomania, will quibble over what is even in plain sight.

Studying an existential crisis of this magnitude requires no scientific apparatus. Consider this classic bullet-through-the-foot statement from Trump aide Myron Ebell: “We will be ceding global leadership of climate policy to China,” Ebell said on 1 February. “I want to get rid of global climate policy, so why do I care who is in charge of it? I don’t care. They can take it as far as I’m concerned, and good luck to them.” [1]

Well, really, who needs luck? Knowing what climate change is, what causes it, and what needs to be done about it is — among many other things — a recipe for printing money, which is why China, the world’s fastest-growing green economy, just invested $360 billion into renewable energy production. US industries either innovate to address the carbon problem, or they join the tobacco companies in the shadowlands of lobbying, litigation, and spin: not quite dead, but no longer really alive.

The default Trump position on America’s scientific institutions is that they have become blunt weapons in the service of an over-centralised state. We know what this would look like were it true (and how far it actually is from American reality) when we look at Stalin’s Russia. Genetics was banned in Russia in 1948 — its institutions destroyed, careers truncated, individuals sacked and internally exiled — because the findings of genetics flatly contradicted promising but badly flawed state-sponsored agricultural trials of new crop varieties. If new varieties could be generated at will (and genetics said they couldn’t), then the countryside could be industrialised overnight, speeding the development of the Soviet Union towards communism within a single generation. The state had ambitions for science and, centralising its efforts around a handful of top-heavy institutions, ensured that those ambitions drowned out the very findings it had paid to obtain.

When climate change-denying Republicans invoke the bogeyman of overpaid lackey climatologists working to a misguided, politically motivated programme, they’re not pointing at nothing. Indeed, they’re pointing at what happened to the largest and best-funded science base in history. The problem is that theirs is an argument from analogy. Which is to say, no argument at all. Flim-flam, if you prefer.

It hardly matters now. If exploited to the hilt by US industry (and let’s be honest, we all want to go out with a bang) Trump’s climate policies — his devotion to fossil fuels and rejection of the Paris protocols — are more than sufficient over four short years to set global temperatures on a course topping 2.5 degrees, at which point our much-maligned globalised civilisation will collapse from the sheer cost of its own insurance premiums.

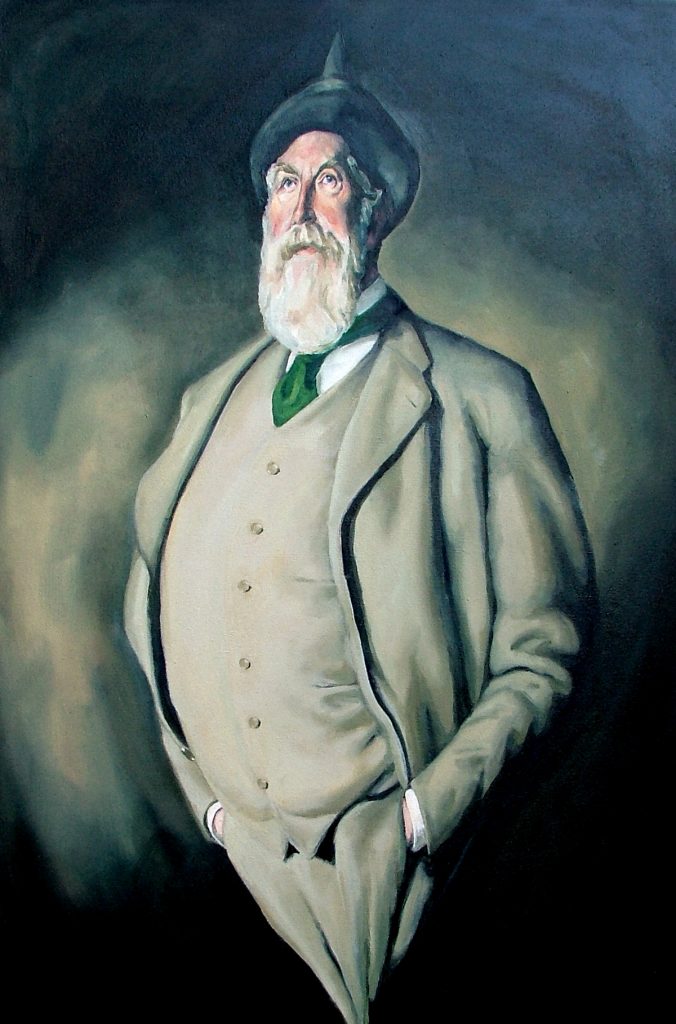

Some more flim-flam while we await the End Times. So Obama was Stalin, was he? Knowledgeable in both science and in politics but unable to separate the one from the other? Then Donald Trump is Nicholas II, the last Tsar of Russia: reactionary, vain, deaf to the entreaties of his ever more carefully hand-picked advisors, until, at the last, only the Rasputin-like whispers of Steve Bannon catch his ear.

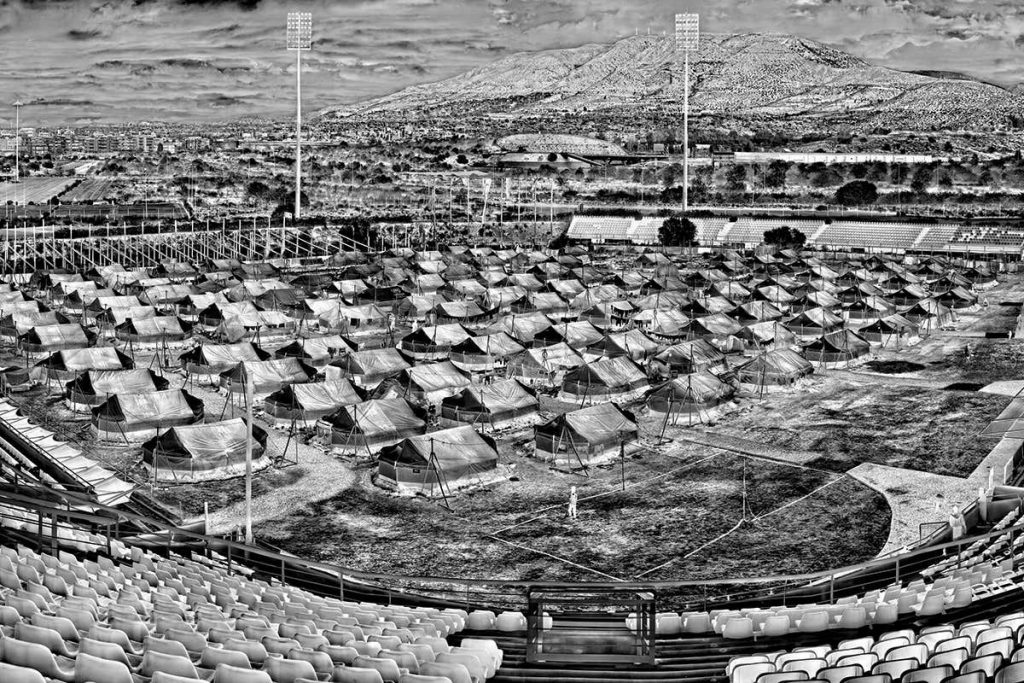

Let’s indulge this bad habit of arguing from analogy a little further, and ask this interesting question: how did Russia’s academics react against Nicholas II’s lame-duck regime? They held marches. They published pamphlets. They organised strikes. They pinned their liberal and cosmopolitan colours to their sleeves, and wrote angry letters to the papers. They achieved virtually nothing until, in 1905, they got canny. They became political. They stood up for an idea of civics rooted in the European enlightenment. They fomented a revolution. They even got the Tsar to convene a parliament, in which they were the ministers.

Ultimately, this “constitutional-democratic” movement failed. It refused to cohere, it sought compromise where it should have fomented discord, collaborated where it should have opposed. It died from politeness. A dozen years later, its failure made Bolshevik extremism possible and the rest, as they say, is history.

History, yes. But not destiny. The people who march in the name of science on Saturday 22 are taking but the first step on what promises to be a long and frightening journey. We should not expect too much from them yet. But neither should we pull our punches. Like it or not, and certainly if Trump lasts into a second term, these people, thanks to their educations and well-thumbed passports, their urbane reflexes and all the advantages that leisure has bestowed on them, are best placed to be the champions of our by then virtually extinguished civic life.

We are going to have to teach these snowflakes how to fight.