Talking to the design engineer Yamanaka Shunji for New Scientist, 23 January 2019

Five years ago, desktop 3D printers were poised to change the world. A couple of things got in the way. The print resolution wasn’t very good. Who wants to drink from a tessellated cup?

More important, it turned out that none of us could design our way out of a wet paper bag.

Japanese designer Yamanaka Shunji calls forth one-piece walking machines from vinyl-powder printers the way the virtuoso Phyllis Chen conjures concert programmes from toy pianos. There’s so much evident genius at work, you marvel that either has time for such silliness.

There’s method here, of course: Yamanaka’s X-Design programme at Keio University turns out objects bigger than the drums in which they’re sintered, by printing them in folded form. It’s a technique lifted from space-station design, though starry-eyed Western journalists, obsessed with Japanese design, tend to reach for origami metaphors.

Yamanaka’s international touring show, which is stopping off at Japan House in London until mid-March, knows which cultural buttons to press. The tables on which his machine prototypes are displayed are steel sheets, rolled to a curve and strung under tension between floor and ceiling, so visitors find themselves walking among what appear to be unfolded paper scrolls. If anything can seduce you into buying a £100 sake cup when you exit the gift shop, it’s this elegant, transfixing show.

“We often make robots for their own sake,” says Yamanaka, blithely, “but usefulness is also important for me. I’m always switching between these two ways of thinking as I work on a design.”

The beauty of his work is evident from the first. Its purpose, and its significance, take a little unpacking.

Rami, for example: it’s a below-the-knee running prosthesis developed for the athlete Takakura Saki, who represented Japan during the 2012 Paralympics. Working from right to left, one observes how a rather clunky running blade mutated into a generative, organic dream of a limb, before being reined back into a new and practical form. The engineering is rigorous, but the inspiration was aesthetic: “We hoped the harmony between human and object could be improved by re-designing the thing to be more physically attractive.”

Think about that a second. It’s an odd thing to say. It suggests that an artistic judgement can spur on and inform an engineering advance. And so, it does, in Yamanaka’s practice, again, and again.

Yamanaka, is an engineer who spent much of his time at university drawing manga, and cut his teeth on car design at Nissan. He wants to make something clear, though: “Engineering and art don’t flow into each other. The methodologies of art and science are very different, as different as objectivity and subjectivity. They are fundamental attitudes. The trick, in design, is to change your attitude, from moment to moment.” Under Yamanaka’s tutelage, you learn to switch gears, not grind them.

Eventually Yamanaka lost interest in giving structure and design to existing technology. “I felt if one could directly nurture technological seeds, more imaginative products could be created.” It was the first step on a path toward designing for robot-human interaction.

Yamanaka – so punctilious, so polite – begins to relax, as he contemplates the work of his peers: Engineers are always developing robots that are realistic, in a linear way that associates life with things, he says, adding that they are obsessed with being more and more “real”. Consequently, he adds, a lot of their work is “horrible. They’re making zombies!”

Artists have already established a much better approach, he explains: quite simply, artists know how to sketch. They know how to reduce, and abstract. “From ancient times, art has been about the right line, the right gesture. Abstraction gets at reality, not by mimicking it, but by purifying it. By spotting and exploring what’s essential.”

Yamanaka’s robots don’t copy particular animals or people, but emerge from close observation of how living things move and behave. He is fascinated by how even unliving objects sometimes seem to transmit the presence of life or intelligence. “We have a sensitivity for what’s living and what’s not,” he observes. “We’re always searching for an element of living behaviour. If it moves, and especially if it responds to touch, we immediately suspect it has some kind of intellect. As a designer I’m interested in the elements of that assumption.”

So it is, inevitably, that the most unassuming machine turns out to hold the key to the whole exhibition. Apostroph is the fruit of a collaboration with Manfred Hild, at Sony’s Computer Science Laboratories in Paris. It’s a hinged body made up of several curving frames, suggesting a gentle logarithmic spiral.

Each joint contains a motor which is programmed to resist external force. Leave it alone, and it will respond to gravity. It will try to stand. Sometimes it expands into a broad, bridge-like arch; at other times it slides one part of itself through another, curls up and rolls away.

As an engineer, you always follow a line of logic, says Yamanaka. You think in a linear way. It’s a valuable way of proceeding, but unsuited to exploration. Armed with fragile, good-enough 3D-printed prototypes, Yamanaka has found a way to do without blueprints, responding to the models he makes as an artist would.

In this, he’s both playing to his strengths as a frustrated manga illustrator, and preparing his students for a future in which the old industrial procedures no longer apply. “Blueprints are like messages which ensure the designer and manufacturer are on the same page,” he explains. “If, however, the final material could be manipulated in real time, then there would be no need to translate ideas into blueprints.”

It’s a seductive spiel but I can’t help but ask what all these elegant but mostly impractical forms are all, well, for.

Yamanaka’s answer is that they’re to make the future bearable. “I think the perception of subtle lifelike behaviour is key to communication in a future full of intelligent machines,” he says. “Right now we address robots directly, guiding their operations. But in the future, with so many intelligent objects in our life, we’ll not have the time or the patience or even the ability to be so precise. Body language and unconscious communication will be far more important. So designing a lifelike element into our machines is far more important than just tinkering with their shape.”

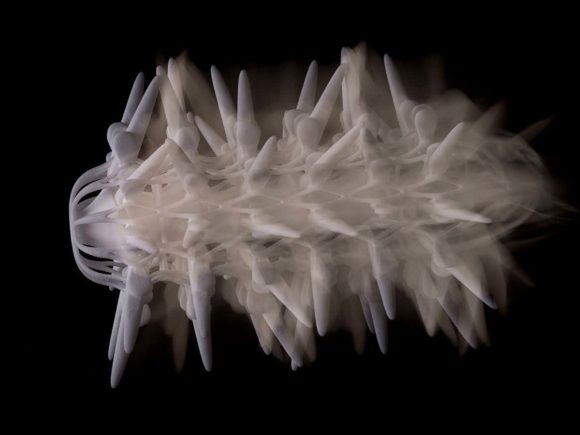

By now we’ve left the gallery and are standing before Flagella, a mechanical mobile made for Yamanaka’s 2009 exhibition Bones, held in Tokyo Midtown. Flagella is powered by a motor with three units that repeatedly rotate and counter-rotate, its movements supple and smooth like an anemone. It’s hard to believe the entire machine is made from hard materials.

There’s a child standing in front of it. His parents are presumably off somewhere agonising over sake cups, dinky tea pots, bowls that cost a month’s rent. As we watch, the boy begins to dance, riffing off the automaton’s moves, trying to find gestures to match the weavings of the machine.

“This one is of no practical purpose whatsoever,” Yamanaka smiles. But he doesn’t really think that. And now, neither do I.