Reading Oliver Morton’s The Moon and Robert Stone and Alan Adres’s Chasing the Moon for The Telegraph, 18 May 2019

I have Arthur to thank for my earliest memory: being woken and carried into the living room on 20 July 1969 to see Neil Armstrong set foot on the moon.

Arthur is a satellite dish, part of the Goonhilly Earth Satellite Station in Cornwall. It carried the first ever transatlantic TV pictures from the USA to Europe. And now, in a fit of nostalgia, I am trying to build a cardboard model of the thing. The anniversary kit I bought comes with a credit-card sized Raspberry Pi computer that will cause a little red light to blink at the centre of the dish, every time the International Space Station flies overhead.

The geosychronous-satellite network that Arthur Clarke envisioned in 1945 came into being at the same time as men landed on the Moon. Intelsat III F-3 was moved into position over the Indian Ocean a few days before Apollo 11’s launch, completing the the world’s first geostationary-satellite network. The Space Race has bequeathed us a world steeped in fractured televisual reflections of itself.

Of Apollo itself, though, what actually remains? The Columbia capsule is touring the United States: it’s at Seattle’s Museum of Flight for this year’s fiftieth anniversary. And Apollo’s Mission Control Center in Houston is getting a makeover, its flight control consoles refurbished, its trash cans, book cases, ashtrays and orange polyester seat cushions all restored.

On the Moon there are some flags; some experiments, mostly expired; an abandoned car.

In space, where it matters, there’s nothing. The intention had been to build moon-going craft in orbit. This would have involved building a space station first. In the end, spooked by a spate of Soviet launches, NASA decided to cut to the chase, sending two small spacecraft up on a single rocket. One got three astronauts to the moon. The other, a tiny landing bug (standing room only) dropped two of them onto the lunar surface and puffed them back up into lunar orbit, where they rejoined the command module and headed home. It was an audacious, dangerous and triumphant mission — but it left nothing useful or reuseable behind.

In The Moon: A history for the future, science writer Oliver Morton observes that without that peculiar lunar orbital rendezvous plan, Apollo would at least have left some lasting infrastructure in orbit to pique someone’s ambition. As it was, “Every Apollo mission would be a single shot. Once they were over, it would be in terms of hardware — even, to a degree, in terms of expertise — as if they had never happened.”

Morton and I belong to the generation sometimes dubbed Apollo’s orphans. We grew up (rightly) dazzled by Apollo’s achievement. It left us, however, with the unshakable (and wrong) belief that our enthusiasm was common, something to do with what we were taught to call humanity’s “outward urge”. The refrain was constant: how in people there was this inborn desire to leave their familiar surroundings and explore strange new worlds.

Nonsense. Over a century elapsed between Columbus’s initial voyage and the first permanent English settlements. One of the more surprising findings of recent researches into the human genome is that, left to their own devices, people hardly move more than a few weeks’ walking distance from where they were born.

This urge, that felt so visceral, so essential to one’s idea of oneself: how could it possibly turn out to be the psychic artefact of a passing political moment?

Documentary makers Robert Stone and Alan Andres answer that particular question in Chasing the Moon, a tie in to their forthcoming series on PBS. It’s a comprehensive account of the Apollo project, and sends down deep roots: to the cosmist speculations of fin de siecle Russia, the individualist eccentricities of Germanys’ Verein fur Raumschiffart (Space Travel Society), and the deceptively chummy brilliance of the British Interplanetary Society, who used to meet in the pub.

The strength of Chasing the Moon lies not in any startling new information it divulges (that boat sailed long ago) but in the connections it makes, and the perspectives it brings to bear. It is surprising to find the New York Times declaring, shortly after the Bay of Pigs fiasco, that Kennedy isn’t nearly as interested in building a space programme as he should be. (“So far, apparently, no one has been able to persuade President Kennedy of the tremendous political, psychological, and prestige importance, entirely apart from the scientific and military results, of an impressive space achievement.”) And it is worthwhile to be reminded that, less than a month after his big announcement, Kennedy was trying to persuade Khrushchev to collaborate on the Apollo project, and that he approached the Soviets with the idea a second time, just days before his assassination in Dallas.

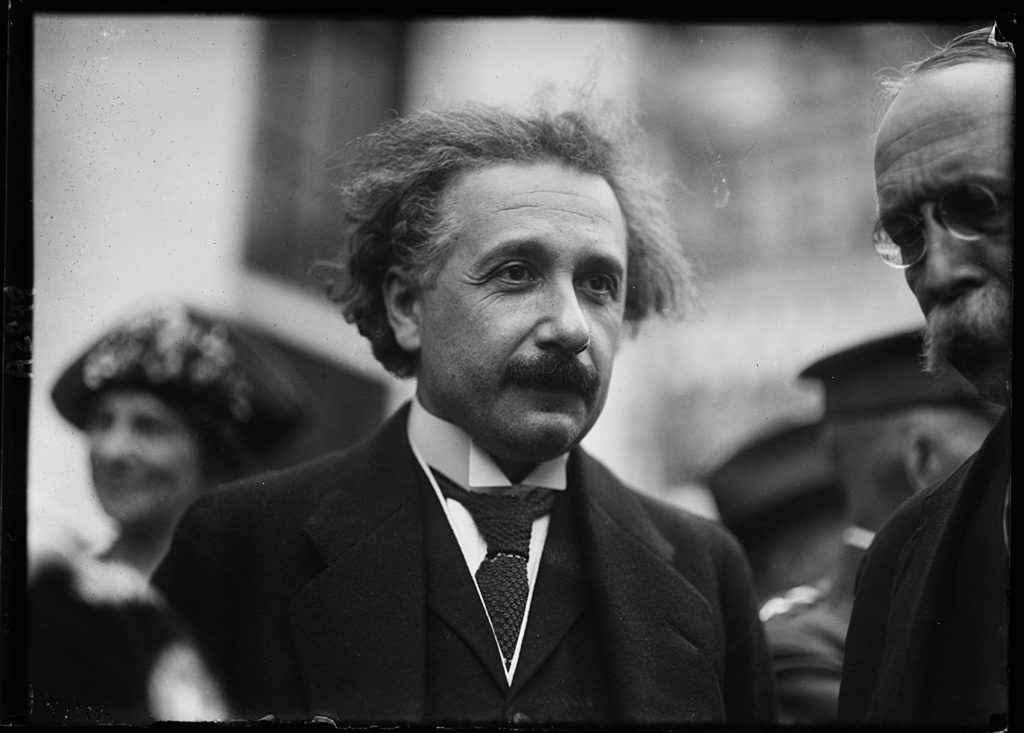

For Kennedy, Apollo was a strategic project, “a wonderful moral substitute for war ” (to slightly misapply Ray Bradbury’s phrase), and all to do with manned missions. NASA administrator James Webb, on the other hand, was a true believer. He could see no end to the good big organised government projects could achieve by way of education and science and civil development. In his modesty and dedication, Webb resembled no-one so much as the first tranche of bureaucrat-scientists in the Soviet Union. He never featured on a single magazine cover, and during his entire tenure he attended only one piloted launch from Cape Kennedy. (“I had a job to do in Washington,” he explained.)

The two men worked well enough together, their priorities dovetailing neatly in the role NASA took in promoting the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act and the government’s equal opportunities program. (NASA’s Saturn V designer, the former Nazi rocket scientist Wernher Von Braun, became an unlikely and very active campaigner, the New York Times naming him “one of the most outspoken spokesmen for racial moderation in the South.”) But progress was achingly slow.

At its height, the Apollo programme employed around two per cent of the US workforce and swallowed four per cent of its GDP. It was never going to be agile enough, or quotidian enough, to achieve much in the area of effecting political change. There were genuine attempts to recruit and train a black pilot for the astronaut programme. But comedian Dick Gregory had the measure of this effort: “A lot of people was happy that they had the first Negro astronaut, Well, I’ll be honest with you, not myself. I was kind of hoping we’d get a Negro airline pilot first.”

The big social change the Apollo program did usher in was television. (Did you know that failing to broadcast the colour transmissions from Apollo 11 proved so embarrassing to the apartheid government in South Africa that they afterwards created a national television service?)

But the moon has always been a darling of the film business. Never mind George Melie’s Trip to the Moon. How about Fritz Lang ordering a real rocket launch for the premiere of Frau im Mond? This was the film that followed Metropolis, and Lang roped in no less a physicist than Hermann Oberth to build it for him. When his 1.8-metre tall liquid-propellant rocket came to nought, Oberth set about building one eleven metres tall powered by liquid oxygen. They were going to launch it from the roof of the cinema. Luckily they ran out of money.

The Verein für Raumschiffahrt was founded by men who had acted as scientific consultants on Frau im Mond. Von Braun became one of their number, before he was whisked away by the Nazis to build rockets for the war effort. Without Braun, the VfR grew nuttier by the year. Oberth, who worked for a time in the US after the war, went the same way, his whole conversation swallowed by UFOs and extraterrestrials and glimpses of Atlantis. When he went back to Germany, no-one was very sorry to see him go.

What is it about dreaming of new worlds that encourages the loner in us, the mooncalf, the cave-dweller, wedded to ascetism, always shying from the light?

After the first Moon landing, the philosopher (and sometime Nazi supporter) Martin Heidegger said in interview, “I at any rate was frightened when I saw pictures coming from the moon to the earth… The uprooting of man has already taken place. The only thing we have left is purely technological relationships. This is no longer the earth on which man lives.”

Heidegger’s worries need a little unpacking, and for that we turn to Morton’s cool, melancholy The Moon: A History for the Future. Where Stone and Anders collate and interpret, Morton contemplates and introspects. Stone and Anders are no stylists. Morton’s flights of informed fancy include a geological formation story for the moon that Von Trier’s film Melancholy cannot rival for spectacle and sentiment.

Stone and Anders stand with Walter Cronkite whose puzzled response to young people’s opposition to Apollo — “How can anybody turn off from a world like this?” — stands as an epitaph for Apollo’s orphans everywhere. Morton, by contrast, does understand why it’s proved so easy for us to switch off from the Moon. At any rate he has some good ideas.

Gertrude Stein, never a fan of Oakland, once wrote of the place, “There is no there there.” If Morton’s right she should have tried the Moon, a place whose details “mostly make no sense.”

“The landscape,” Morton explains, “may have features that move one into another, slopes that become plains, ridges that roll back, but they do not have stories in the way a river’s valley does. It is, after all, just the work of impacts. The Moon’s timescape has no flow; just punctuation.”

The Moon is Heidegger’s nightmare realised. It can never be a world of experience. It can only be a physical environment to be coped with technologically. It’s dumb, without a story of its own to tell, so much “in need of something but incapable of anything”, in Morton’s telling phrase, that you can’t even really say that it’s dead.

So why did we go there, when we already knew that it was, in the words of US columnist Milton Mayer, a “pulverised rubble… like Dresden in May or Hiroshima in August”?

Apollo was the US’s biggest, brashest entry in its heart-stoppingly exciting – and terrifying – political and technological competition with the Soviet Union. This is the matter of Stone and Anders’s Chasing the Moon, as a full a history as one could wish for, clear-headed about the era and respectful of the extraordinary efforts and qualities of the people involved.

But while Morton is no less moved by Apollo’s human adventure, we turn to his book for a cooler and more distant view. Through Morton’s eyes we begin to see, not only what the moon actually looks like (meaningless, flat, gentle, a South Downs gone horribly wrong) but why it conjures so much disbelief in those who haven’t been there.

A year after the first landing the novelist Norman Mailer joked: “In another couple of years there will be people arguing in bars about whether anyone even went to the Moon.” He was right. Claims that the moon landing were fake arose the moment the Saturn Vs stopped flying in 1972, and no wonder. In a deep and tragic sense Apollo was fake, in the sense that it didn’t deliver the world it had promised.

And let’s be clear here: the world it promised would have been wonderful. Never mind the technology: that was never the core point. What really mattered was that at the height of the Vietnam war, we seemed at last to have found that wonderful moral substitute for war. “All of the universe doesn’t care if we exist or not,” Ray Bradbury wrote, “but we care if we exist… This is the proper war to fight.”

Why has space exploration not united the world around itself? It’s easy to blame ourselves and our lack of vision. “It’s unfortunate,” Lyndon Johnson once remarked to the astronaut Wally Schirra, “but the way the American people are, now that they have developed all of this capability, instead of taking advantage of it, they’ll probably just piss it all away…” This is the mordant lesson of Stone and Andres’s otherwise uplifting Chasing the Moon.

Oliver Morton’s The Moon suggests a darker possibility: that the fault lies with the Moon itself, and, by implication, with everything that lies beyond our little home.

Morton’s Moon is a place defined by absences, gaps, and silence. He makes a poetry of it, for a while, he toys with thoughts of future settlement, he explores the commercial possibilities. In the end, though, what can this uneventful satellite of ours ever possibly be, but what it is: “just dry rocks jumbled”?