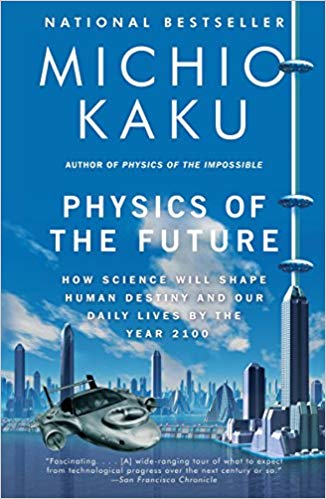

Physics of the Future: How Science Will Shape Human Destiny and Our Daily Lives by the Year 2100 by Michio Kaku (Allen Lane) for The Sunday Telegraph.

There are books written to so tight a formula, you slide off them. They elude categories of good and bad. They just are. Anecdotes from filming programmes for the BBC, Discovery and the Science Channel provide the leavening agent for Michio Kaku’s brick of a book about how technology will change our daily lives over the next hundred years. (Thanks to that technology, some us will still be around to see if he’s right.)

Each chapter explores a set of technologies, from artificial intelligence to energy, space travel to medicine, and offers near, middle and long-term predictions. Each opens with a synopsis of a classical myth – the promise being that we will eventually acquire a Godlike control over our lives and our surroundings. Like the heroes of old, we ought to be careful what we wish for. Still, the outlook is bright. Dazzlingly bright. At times, unbearable.

In a chapter dealing with telepresence, Kaku gushingly evokes the moment when “from the comfort of the beach, we will be able to teleconference to the office by blinking”, using special contact lenses. If that wasn’t disconcerting enough, Kaku then quotes approvingly from Max Frisch that “Technology [is] the knack of so arranging the world that we don’t have to experience it”. Is the co-founder of string theory having us on?

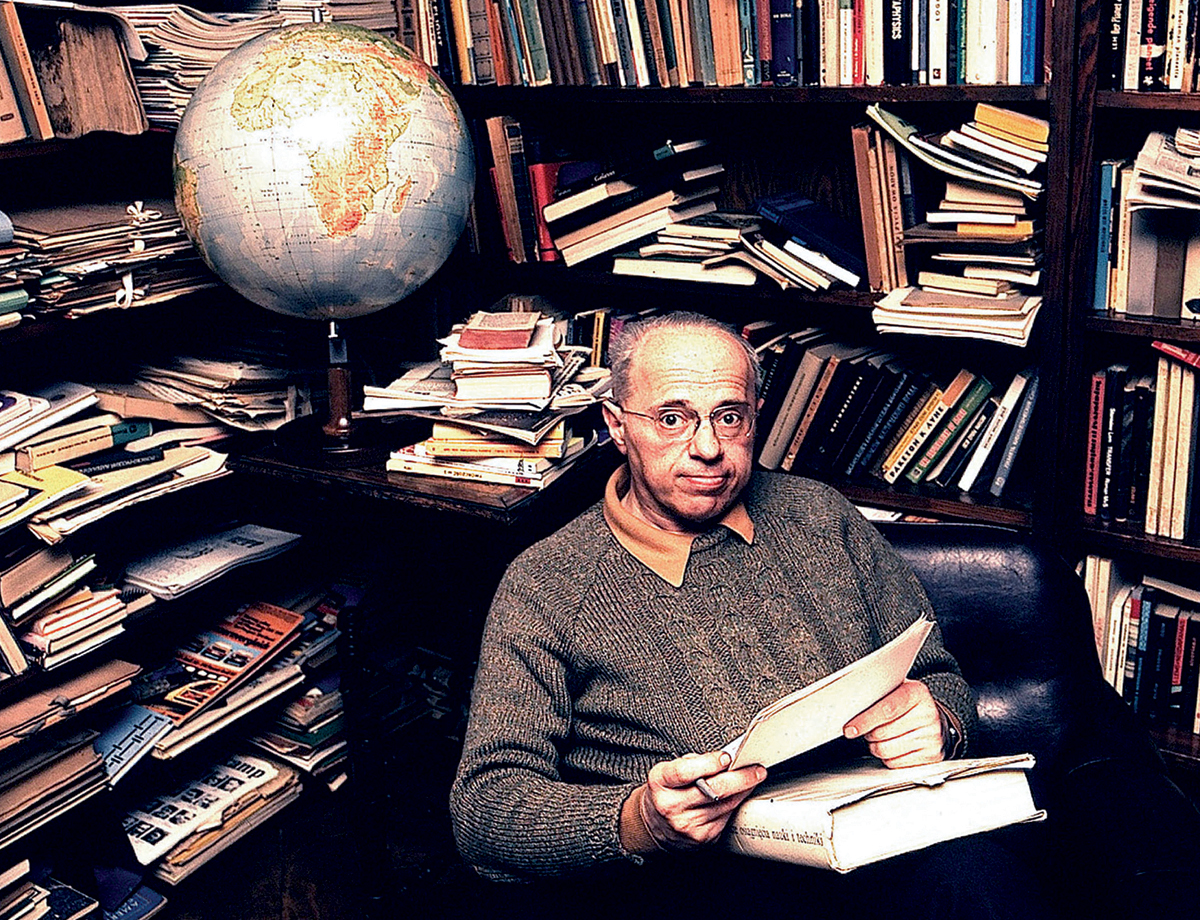

The thing is, Michio Kaku the “science communicator” is like a character from a Hollywood film: an accomplished real-life version of the ex-hippy who directs Area 51’s secret subterranean laboratory in the film Independence Day (“As you can imagine, they don’t let us out much”).

Indeed, Kaku’s naivety is enough to chill the marrow when he explains how United States drones are “targeting terrorists with deadly accuracy in Afghanistan and Pakistan”. (A respected study published by an American think-tank last year concluded that almost a third of those killed in drone strikes between 2004 and February 2010 were civilians.)

Naivety is one side of the coin, the other is Kaku’s enthusiasm for what science and technology can bring to our day-to-day lives; lives that have always been, and always will be, directed by what Kaku calls “the caveman principle”. As he says: “Our wants, dreams, personalities and desires have not changed much in 100,000 years.”

There are strange gaps in Kaku’s account. No mention, for example, of the fact that every ecosystem on the planet is suffering measurable decline and that our natural resources are shrinking to the point where we can’t afford them. (Kaku says that cables made of carbon nanotubes are set to replace copper wiring because they’re lighter and more efficient; he says nothing about the spiralling cost of copper.) There is virtually nothing here about how technology and science, mishandled over the next 100 years, may prove to be the medicine that kills the patient.

This is a missed opportunity. The technology of the next 100 years will be environmental. It will be grown. Be they self-assembling robots or genetically engineered bacteria, many of our most recent inventions are acquiring lives and evolving behaviours of their own. Are their creators oblivious to the environmental ramifications of their work? If so, we are in danger from science getting out of control. I don’t think the scientific community is so clueless, and I don’t imagine Kaku thinks so, either. But it will take a more sophisticated book than this one to address our fears.

Physics of the Future will be very easy for pessimists to dismiss. For those who can put their anxieties aside, though, there are rewards. Kaku writes very well about exponential thinking. In the mid-Nineties, for example, he delivered a keynote address at a conference in Frankfurt, predicting that by 2020, everyone would have a CD-ROM with their genome recorded on it. The Human Genome Project had just cost $3billion, and some in the audience responded with indignation.

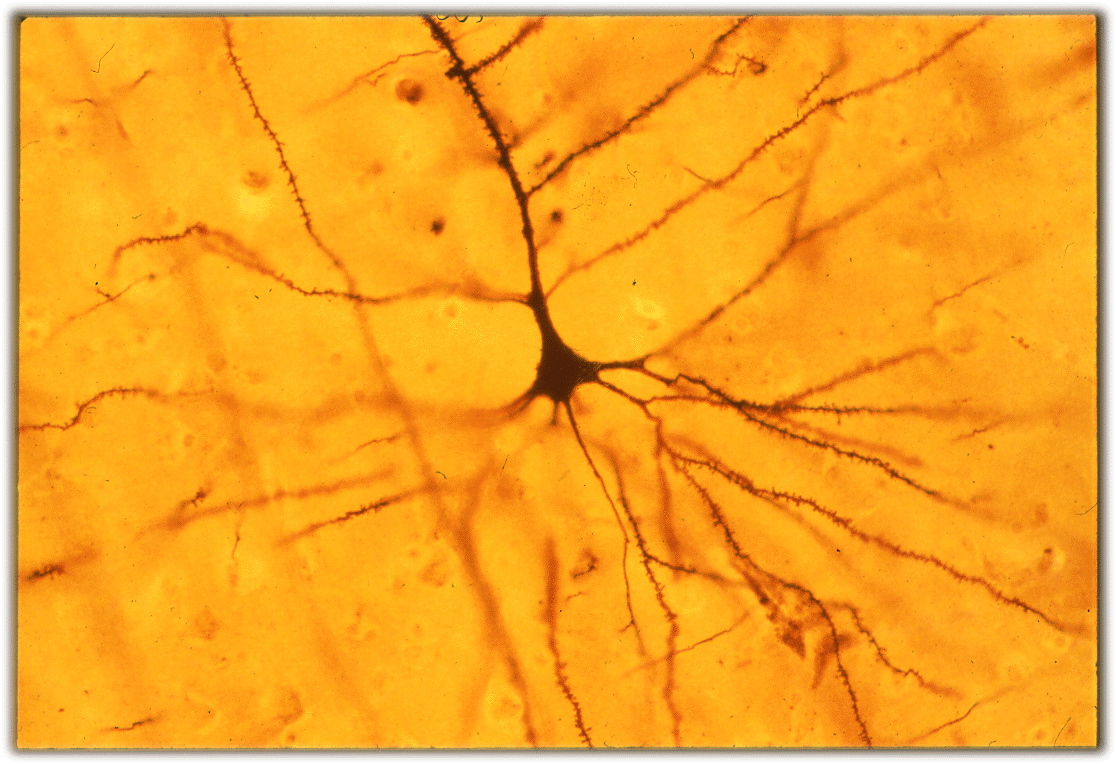

But Kaku had a long-term trend in the history of computing hardware on his side. For as long as computers have been around, a dollar buys twice as much computing power as it did two years ago. Examining a CD-ROM from Vanderbilt University, Kaku recently discovered that he thankfully does not carry his family’s susceptibility to Alzheimer’s. His prediction about personalised genomes was wrong: he’d been far too conservative.

Spinning I-told-you-so stories from exponential thinking is easy. Making the exponential character of technological progress stick in the reader’s head, so that they come to look at the world differently, is a more onerous task, and one Kaku accomplishes well.

Three hundred interviews with leading scientists and engineers went into this book. Still, Physics of the Future has an old-fashioned flavour. It is partisan about technology in a way that smacks of Gerard K O’Neill’s deliriously technocratic vision of space exploration, The High Frontier.

For those of us who read O’Neill in 1976 (and who of us, reading it, was not inspired?) Physics of the Future works best as a homage to that book, that time, and that us-against-the-world vision of technology. Kaku the futurist may be showing his age, but that’s not a bad thing. There’s a place on the shelves for sheer wonder, and, if nothing else, Kaku reminds us that the Seventies did wonder well.