And there’s more to come: visit

The Smoke went through the usual chaotic process of reinvention as I got more and more interested in why I wanted to do this project in the first place. And it can be best summed up by a WhatsApp message I sent to someone the other day as I came out of King’s Cross Station: IT’S THE FUTURE AND I DON’T UNDERSTAND…

Talking about The Smoke and others to Jonathan Thornton for Fantasy Hive, March 27 2018

Visiting the Science Gallery, Dublin for New Scientist, 14 April 2018

Had you $1800 to spend on footwear in 2012, you might have considered buying a pair of RayFish sneakers. Delivery would have taken a while because you were invited to design the patterned leather yourself. You would have then have had to wait while the company grew a pair of transgenic stingrays in their Thai aquaculture facility up to the age where their biocustomised skins could be harvested.

Alas, animal rights activists released the company’s first batch of rays into the wild before harvesting could take place, and the company suspended trading. Scuba divers still regularly report sightings of fish sporting the unlikely colourations that were RayFish’s signature.

RayFish was, you’ll be pleased to hear, a con, perpetrated by three Dutch artists five years ago. It now features in Fake, the latest show at the Science Gallery, Dublin, an institution that sells itself as the place “where art and science collide”.

The word “collide” is well chosen. “We’re not experts on any one topic here,” explains Ian Brunswick, the gallery’s head of programming, “and we’re not here to heal any kind of ‘rift’ between science and art. When we develop a show, we start from a much simpler place, with an open call to artists, designers and scientists.” They ask all the parties what they think of the new idea, and what can they show them. Scientists in particular, says Brunswick, often underestimate which elements of their work will captivate.

Founded under the auspices of Dublin’s Trinity College, the Science Gallery is becoming a global brand thanks to the support of founding partner Google.org. London gets a gallery later this year; Bangalore in 2019. The aim is to not to educate, but to inspire visitors to educate themselves.

Brunswick recalls how climate change, in particular, triggered this sea-change in the way public educators think about their role: “I think many science shows have been operating a deficit model: they fill you up like an empty vessel, giving you enough facts so you agree with the scientists’ approach. And it doesn’t work.” A better approach, Brunswick argues, is to give the audience an immediate, visceral experience of the subject of the show.

For example, in 2014 Dublin’s Science Gallery called its climate change show “Strange Weather”, precisely to explore the fact that weather and climate change are different things, and that weather is the only phenomenon we experience directly on a daily basis. It got people to ask how they knew what they knew about the climate – and what knowledge they might be missing.

Playfulness characterises the current show. Fakery, it seems, is bad, necessary, inevitable, natural, dangerous, creative, and delightful, all at once. There are fictional animals here preserved in jars besides real specimens: are they fake, or merely out of context? And you can (and should) visit the faux-food deli and try a caramelised whey product here from Norway that everyone calls cheese because what the devil else would you call it?

Then there’s a genuine painting that became a fake when its unscrupulous owner manipulated the artist’s signature. And the Chinese fake phones that are parodies you couldn’t possibly mistake for the real thing: from Pikachu to cigarette packets. There’s a machine here will let you manipulate your fake laugh until it sounds genuine.

Fake’s contributing artists have left me with the distinct suspicion that the world I thought I knew is not the world.

Directly above RayFish’s brightly patterned sneakers, on the upper floor of the gallery, I saw Barack Obama delivering fictional speeches. A work in progress by researchers from the University of Washington, Synthesizing Obama is a visual form of lip-synching in which audio files of Obama speaking are converted into realistic mouth shapes. These are then blended with video images of Obama’s head as he delivers another speech entirely.

It’s a topical piece, given today’s accusatory politics, and a chilling one.

Reading Catching Thunder by by Eskil Engdal and Kjetil Saeter for the Daily Telegraph, 1 April 2018

In March 23 1969 the shipbuilders of Ulsteinvik in Norway launched a stern trawler called the Vesturvon. It was their most advanced factory trawler yet, beautiful as these ships go, and big: outfitted for a crew of 47.

In 2000, after many adventures, the ship suffered a midlife crisis. Denied a renewal of their usual fishing quota, its owners partnered up with a Russian company and sent the ship, renamed the Rubin, to ply the Barents Sea. There, in the words of Eskil Engdal and Kjetil Saeter, two Norwegian journalists, the ship slipped ineluctably into “a maelstrom of shell corporations, bizarre ships registers and shady expeditions”.

In the years that followed, the ship changed its name often: Kuko, Wuhan No 4, Ming No 5, Batu 1. Its crew had to look over the side of the ship at the name plate, attached that morning to the stern, to find out which ship they were on. Flags from countries such as Equatorial Guinea, Mauritania and Panama were kept in a cardboard box.

It fell to a Chilean, Luis Cataldo, to be captaining the ship (then named the Thunder) on December 17 2014 – the day when, off Antarctica’s windy Banzare Bank, in the middle of an illegal fishing expedition, it was spotted by the Bob Barker, a craft belonging to the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society. The Bob Barker’s captain got on the radio and told Cataldo his vessel was wanted by Interpol and should follow him to port.

Cataldo retorted that he wasn’t inclined to obey a ship whose black flag bore a skull (albeit with a shepherd’s crook and a trident instead of crossbones). And it is fair to say that the Sea Shepherd organisation, whose mission “is to end the destruction of habitat and slaughter of wildlife in the world’s oceans”, has enjoyed a fairly anomalous relationship with nautical authority since its foundation in 1977.

So began the world’s longest sea chase to date, recorded with flair and precision in Catching Thunder, Diane Oatley’s effortlessly noir translation of Engdal and Saeter’s 2016 Norwegian bestseller. The book promises all the pleasures of a crime novel, but it is after bigger game: let’s call it the unremitting weirdness of the real world.

This is a book about fish – and also a chase narrative in which the protagonists spend most of the time sailing in circles and sending each other passive-aggressive radio messages. (“You are worried about the crew, and now all the Indonesians are nervous,” Cataldo complains. “One person attempted to take his life. Over.”)

It’s about attempting to regulate the movement of lumps of steel weighing more than 650 tons which, if they want, can thug their way out of any harbour whether they’ve been “impounded” or not, and it’s about the sheer slow-mo clumsiness of ship-handling.

At one point the Thunder “moves in circles, directing a searchlight on the Bob Barker, then suddenly stops and drifts for a few hours. Then the mate puts the ship in motion again, heading for a point in the middle of nowhere.” There’s no Hollywood hot-headedness here. The violence here is rare, veiled and, when it comes, unstoppable and ice-cold.

The Thunder was wanted for hunting the Patagonian toothfish, a protected species of “petulant and repulsive” giants that can grow to a weight of 120kg and live more than 50 years. When the Bob Barker caught sight of it in the Southern Ocean, no one could have guessed that their chase would last for 110 days.

Stoked by Sea Shepherd’s YouTube campaign, the pursuit became a cause célèbre and the Bob Barker’s hardened crew were prepared for the long game: “As long as the two ships are operating without using the engines, it is only the generators that are consuming fuel. If it continues like this, they can be at sea for two years.”

Engdal and Saeter must keep their human story going while doing justice to the scale of their subject. At the start, their subject is the fishing industry, in which a cargo of frozen toothfish can go “on a circumnavigation of the world from the Southern Ocean to Thailand, then around the entire African continent, past the Horn of Africa, across the Indian Ocean and into the South China Sea before ending up in Vietnam.” But they also have something to say about the planet.

Suppose you catch fish for a living. If you saw that your catch was dwindling, you might limit your days at sea to ensure that you can continue to fish that species in future years. This isn’t “ecological thinking”; it’s simple self-interest. In the fishing industry, though, self-interest works differently.

And in a chapter about Chimbote in Peru, the authors hit upon a striking metonym for the global mechanisms denuding our seas.

The Peruvian anchovy boom of the late 2000s turned Chimbote from a sleepy village into Peru’s busiest fishing port. Fifty factories exuded a stench of rotten fish, and pumped wastewater and fish blood into the ocean, to the point where the local ecosystem was so damaged that an ordinary El Niño event finished off the anchovy stocks for good.

The point is this: fishing companies are not fisherfolk. They are companies: lumps of capital incorporated to maximise returns on investment. It makes no sense for an extraction company to limit its consumption of a resource.

Once stocks have been reduced to nothing, the company simply reinvests its capital in some other, more available resource. You can put rules in place to limit the rapaciousness of the enterprise, but the rapaciousness is baked in. Rare resources are doomed to extinction eventually because the rarer a resource is, the more expensive it is, and the more incentive there is to trade in it. This is why, past a certain point, rare stocks hurtle towards zero.

Politically savvy readers will find, between the lines, an account here of how increasingly desperate governments are coming to a rapprochement with the Sea Shepherd organisation, whose self-consciously piratical founder Paul Watson declared in 1988: “We hold the position that the laws of ecology take precedence over the laws designed by nation states to protect corporate interests.”

Watson’s position seems legally extreme. But 30 years on, with an ecological catastrophe looming, many maritime law enforcers hardly care. Robbed of income and ecological capital, some countries are getting gnarly. In 2016, Indonesian authorities sank 170 foreign fishing vessels in less than two years. They would like to sink many more: according to this daunting thriller, 5,000 illegal fishing vessels ply their waters at any one time.

Rounding up some cosmological pop-sci for New Scientist, 24 March 2018

IN 1872, the physicist Ludwig Boltzmann developed a theory of gases that confirmed the second law of thermodynamics, more or less proved the existence of atoms and established the asymmetry of time. He went on to describe temperature, and how it governed chemical change. Yet in 1906, this extraordinary man killed himself.

Boltzmann is the kindly if gloomy spirit hovering over Peter Atkins’s new book, Conjuring the Universe: The origins of the laws of nature. It is a cheerful, often self-deprecating account of how most physical laws can be unpacked from virtually nothing, and how some constants (the peculiarly precise and finite speed of light, for example) are not nearly as arbitrary as they sound.

Atkins dreams of a final theory of everything to explain a more-or-less clockwork universe. But rather than wave his hands about, he prefers to clarify what can be clarified, clear his readers’ minds of any pre-existing muddles or misinterpretations, and leave them, 168 succinct pages later, with a rather charming image of him tearing his hair out over the fact that the universe did not, after all, pop out of nothing.

It is thanks to Atkins that the ideas Boltzmann pioneered, at least in essence, can be grasped by us poor schlubs. Popular science writing has always been vital to science’s development. We ignore it at our peril and we owe it to ourselves and to those chipping away at the coalface of research to hold popular accounts of their work to the highest standards.

Enter Brian Clegg. He is such a prolific writer of popular science, it is easy to forget how good he is. Icon Books is keeping him busy writing short, sweet accounts for its Hot Science series. The latest, by Clegg, is Gravitational Waves: How Einstein’s spacetime ripples reveal the secrets of the universe.

Clegg delivers an impressive double punch: he transforms a frustrating, century-long tale of disappointment into a gripping human drama, affording us a vivid glimpse into the uncanny, depersonalised and sometimes downright demoralising operations of big science. And readers still come away wishing they were physicists.

Less polished, and at times uncomfortably unctuous, Catching Stardust: Comets, asteroids and the birth of the solar system is nevertheless a promising debut from space scientist and commentator Natalie Starkey. Her description of how, from the most indirect evidence, a coherent history of our solar system was assembled, is astonishing, as are the details of the mind-bogglingly complex Rosetta mission to rendezvous with comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko – a mission in which she was directly involved.

It is possible to live one’s whole life within the realms of science and discovery. Plenty of us do. So it is always disconcerting to be reminded that longer-lasting civilisations than ours have done very well without science or formal logic, even. And who are we to say they afforded less happiness and fulfilment than our own?

Nor can we tut-tut at the way ignorant people today ride science’s coat-tails – not now antibiotics are failing and the sixth extinction is chewing its way through the food chain.

Physicists, especially, find such thinking well-nigh unbearable, and Alan Lightman speaks for them in his memoir Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine. He wants science to rule the physical realm and spirituality to rule “everything else”. Lightman is an elegant, sensitive writer, and he has written a delightful book about one man’s attempt to hold the world in his head.

But he is wrong. Human culture is so rich, diverse, engaging and significant, it is more than possible for people who don’t give a fig for science or even rational thinking to live lives that are meaningful to themselves and valuable to the rest of us.

“Consilience” was biologist E.O. Wilson’s word for the much-longed-for marriage of human enquiry. Lightman’s inadvertent achievement is to show that the task is more than just difficult, it is absurd.

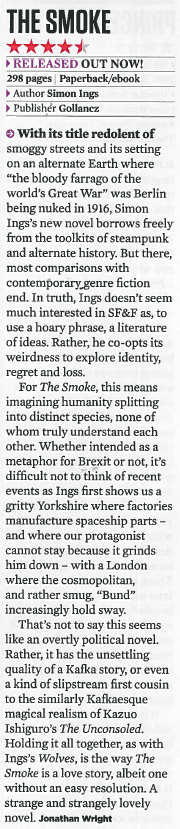

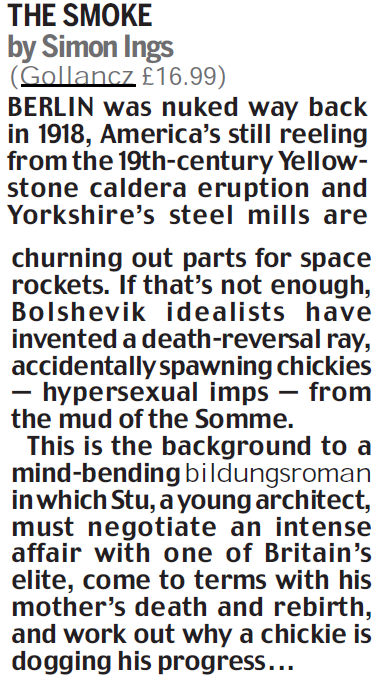

Interzone

SFX

Daily Mail

Gary K Wolfe in Locus, 7 June 2018

Simon Ings’s The Smoke – his second new SF novel in four years after having taken more than a decade off for more mainstream projects (including a fascinating study of science under Stalin) – is quite a bit more radical than 2014’s Wolves, which was judiciously and elegantly restrained in its examination of the possible impact of augmented reality, but it shares with that novel a deep focus on character that at times hardly seems to need the SF armature at all. One of the most compelling and beautifully realized chapters, in fact, is a dinner party which the protagonist and part-time narrator Stuart Lanyon, an aspiring architect, attends with his working-class father Bob, his brother Jim (an astronaut in training who hopes to become the first Yorkshireman in space), his brilliant girlfriend Fel, her wealthy and powerful physician father Georgy, and Georgy’s companion Stella, who is trying to develop a rather cheesy-sounding TV series about alien invasions on the moon (Ings mentions Gerry and Sylvia Anderson in the acknowledgments). Stella, in turn, is Stuart’s own aunt – the sister to his mother Betty, who is dying of cancer. The tensions of class and privilege, of generations, of conflicting aspirations, and of family dynamics would be at home, and just as impressive, in any number of mid-20th-century British novels of domestic realism. But before we even get to this point, Ings has placed these characters in a radically defamiliarized setting that only magnifies those classic tensions in a kind of distorting mirror. By the time we’re done, we’ve gotten ourselves into a complex stew of alternate history, mid-1950s SF dreams (not just the TV show, but a version of the Orion atomic spaceship project), class distinctions turned into biological processes, a very weird form of life extension biotech, and maybe even a war with the moon.

Early on, we are given to understand that the “Great War” ended in 1916 with the nuking of Berlin and the irradiation of Europe, that a Yellowstone Eruption in 1874 devastated North America and led to a decade-long global winter, and that – more to the immediate point of how this world diverged from ours – the real-life Russian embryologist Alexander Gurwitsch perfected a “biophotonic ray,” which led to a form of biotech that eventually led to “the speciation of mankind.” Not too surprisingly, that speciation tended to fall along class lines in a way not too different from those in Wells’s The Time Machine, but much more rapidly, and with more catastrophic results. At the top of the sociobiological heap is an enhanced class of urbanites call the Bund, who have taken over large swaths of London (usually referred to as “the Smoke”), and whose advanced technology has already sent robot miners to the moon. Ordinary, “unaccommodated” humans (for which we might as well read Yorkshiremen, given the setting) constitute a kind of lower middle class, with its own more bluntly industrial approach to space exploration represented by the Orion-style spaceship being constructed in Australia. A species of despised smaller “sub-humans” called Chickies, an unfortunate mutational aftereffect of the Great War, in some ways recall Margaret Atwood’s “Crakers” in that they cast a kind of sexual spell over humans. As we learn from a clever and unexpected point-of-view shift in the novel’s opening section, though, they aren’t quite as inarticulate or subhuman as they might at first seem.

That point-of-view shift represents another somewhat risky decision on Ings’s part. Like many, I find that second-person viewpoints, outside of epistolary tales, can be pretty annoying unless managed carefully – we never know up front if the narrator is speaking to the reader, to another character, or to themselves, and it can quickly begin to feel like an excessively coy game of hide-and-seek. Ings sustains this for most of the first two chapters, including most of the background information mentioned above, but then shifts almost seamlessly to a first-person viewpoint whose nature I should not disclose here. The novel’s second and longest section is a more conventional first-person narration by Stuart, and separate italicized passages outside the main narrative detail the experiences of Stuart’s astronaut brother Jim, in what amounts to a fairly conventional space-disaster tale of its own.

For all the inventiveness of the alternate UK presented here, the novel’s greatest power derives from Stuart’s own narration – his own insecurity at why the brilliant and enhanced Fel should want to be with him, the classic Lawrencian tension between his architectural and social ambitions and his working-class dad, the compromise of those ideals by agreeing to design sets for his aunt’s tacky SF TV series (which is described in such detail that Ings is clearly having fun with it), and his helplessness at his mother’s debilitating disease. But the mother, Betty, also comes to represent the intersection of SF ideas and character dynamics in a way that most of the novel only implies. That doctor, Georgy Chernoy, the paramour of Stuart’s aunt and the father of his girlfriend, has developed a medical procedure which seems to promise a kind of immortality, but at the cost of having the patient’s mind downloaded into that of a rapidly growing infant, who needs to learn motor skills and re-orient to the world in order to make those memories functional. When Betty becomes one of these new children – over her distraught husband’s fierce objections – the result is a surrealist nightmare and a Freudian dream: Stuart facing the prospect of changing his infant mom’s diapers, the mom screaming Yorkshirewoman invectives in the voice of a toddler, the father hopelessly unable to deal at all. As convincing and insightful as the family drama is on its own terms, situations like this remind us that Ing could not have told this haunting tale without the SF, and he couldn’t have told it with only the SF. It’s a classic example of how SF need not be in opposition to the traditional template of domestic realism, but can amplify it exponentially.

Ings’s Vergilings by Adam Roberts

The first time I read Simon Ings’s The Smoke (Gollancz 2018) I liked it very much without any great sense I understood what was going on. I often react to Ings’s work like that. It’s not that he writes strange things (although he certainly does write strange things) so much as there being something ever-so-slightly off-kilter about his strangeness, something to which it’s tricky to tune-in, or at least something I find tricky. He doesn’t peddle common-garden Uncanny, and is uninterested in the grander varieties of Lovecraftian Weird. Perhaps there are affinities between what he writes and Surrealism, a mode of art that’s almost always close-focus, somatic rather than cosmic, cod-psychoanalytic in its oddities rather than just random for random’s sake.

In the alt-history of The Smoke the “Great War” ended in 1916 with the atom-bombing of Berlin and the irradiation of much of Europe (a massive eruption at Yellowstone in 1874 had already devastated North America and provoked global winter). But Ings is not particularly bothered by the sorts of games alt-historians tend to play, and his twentieth-century Britain is in many ways unchanged from actuality. The difference is that Ings chucks a magical new tech into his mix, a “biophotonic ray” invented by Russian scientist Aleksander Gurswitsch (a real-life figure, of course). The Gurswitsch ray can reanimate dead flesh—directed at the mud-sunk slain of the Western Front it inadvertently resurrected a caste of beings called “Chickies”—as well as genetically alter flesh to produce new human species. Connectedly, the Jews of the world have reconfigured themselves as the “Bund”, a people who live by sociological principles of collectivity who also happen to be immensely talented when it comes to inventing new technological devices. London, the novel’s titular city, is divided between regular Londoners and a large compound south of the river occupied by the Bund.

The focalising character in Ings’s narrative is Stuart, a yorkshireman who was previously married to Fel, from the Bund. As the novel opens Stuart has, painfully, separated from his wife, and left their London apartment to come back to stay with his no-nonsense father. Stuart’s mother Betty is dying of a debilitating illness, a situation in which both men find it difficult to cope. The family has another son, Stuart’s brother Jim, who is an astronaut stationed in Woomera, Australia, where the British are about to launch an enormous “Project Orion”-style spaceship, “HMS Victory”, into orbit. The Bund are ahead of the Brits, though: opting for automated miniaturisation over grandstanding big engineering they have already launched many probes into space, and have even landed robot miners on the moon.

But it misrepresents the novel to lay out all this context in this way. The Smoke fills us in on all this as we read, but Ings is more interested in the odder, more psychological or psychosexual corners and crevices of his story. Stuart misses his wife Fel, and often thinks back to the time they spent in London designing costumes for a sciencefictional TV show called DARE, an Ingsian version of the Gerry and Sylvia Anderson show UFO. He is prey to the sexual glamour Chickies can (it seems) cast over ordinary humans. Stuart always carries with him a little mannikin made of grass that seems to have some occult significance to him. He obsessively reads the “onion-skin pages” of his “mother’s Aeneid”—this is how the novel’s first chapter opens:

Troy has fallen. The belly of the wooden horse has splintered open in the town square, vomiting forth Greek elites. The gates are torn open and the city, gaping, lost, runs with blood.

This looks forward to the final section of the novel, where [spoiler] HMS Victory is succesfully launched only to be blasted to pieces in orbit by the Bund, killing its crew including Jim. The novel ends with Stuart remembering his wife Fel at night “sitting up on pillows, the reading lamp on, poring over an old book”. The last lines of The Smoke are: “she lifted the book for me to see—Mum’s Aeneid—and said ‘the old stories are the best.’”

Stuart’s mother Betty is offered the chance to evade her inevitable death by opting for a strange procedure pioneered by a certain Dr Georgy Chernoy: the deal is, you become pregnant (even at Betty’s advanced age) with a fetus into which your own consciousness is downloaded, before your original body expires. This results in a population of infants containing adult consciousnesses, painstakingly relearning their motor-skills, and reconnecting with their memories by toddling around scale-models of famous London landmarks. It’s very odd and sometimes (as when Stuart has to change his infant mum’s nappies as she shouts adult invectives in the voice of a toddler) pretty disturbing. One final weirdness is the latest high-tech innovation of the Bund: they destroy the HMS Victory to stymie British space ambitions, but they then bring the dead crew back to life, inside the bodies of small plastic toy figures, “Action Man”-style mannikins. So it is that Stuart reunites with his dead brother Jim.

When I first read all this it puzzled me, but in a good way. It stirred my imagination as much as it baffled me. I liked its oddness and richness: Ings is doing things SF rarely does. Then I had occasion to re-read it, something I don’t do enough with recent fiction I fear. Looking through it again, I think—I think—I understand what’s going on here, now.

The Smoke now seems to me (which it didn’t really, before) a novel about just how strange it is that old clapped-out life can produce new life; a novel about the sheerly existential weirdness of this basic human fact, that novelty comes out of our expiring flesh the way that it does. I’m in my 50s and my bodily being-in-the-world is increasingly run-down and ruinous and crappy, yet my children, engendered of my and my wife’s old flesh, are young, vital, fresh. How? It’s the weirdness of children as such, here manifested in the Bund’s surreal experiments, dying bodies literally pregnant with their to-be-reincarnated selves, reborn consciousnesses inside plastic toys action-men, the Chickies reborn out of the mud of Flanders. In each case the novel dramatises both the way old people decline, physically and mentally, that the woods decay the woods decay and fall, and the surreal way newness comes into the world, blending surrealism and elegy in a powerful way.

This, I now think, is why the book starts and ends with the Aeneid. A little while ago, in a different context, I blogged about Circe’s appearance in Aeneid 7. In book 6, Aeneas visits the underworld, having seen both the punished distorted into tortuous shapes by the consequences of their sinfulness, and the blissful existence of the blessed. Book 7 starts by addressing one more dead person: Aeneas’s old nurse Caieta, who is buried on a piece of coastline that subsequently becomes the promontory and town of Caieta. Then Aeneas sails away:

At pius exsequiis Aeneas rite solutis,

aggere composito tumuli, postquam alta quierunt

aequora, tendit iter velis portumque relinquit.

Adspirant aurae in noctem nec candida cursus

Luna negat, splendet tremulo sub lumine pontus.

Proxima Circaeae raduntur litora terrae,

dives inaccessos ubi Solis filia lucos

adsiduo resonat cantu tectisque superbis

urit odoratam nocturna in lumina cedrum,

arguto tenuis percurrens pectine telas.

Hinc exaudiri gemitus iraeque leonumv

vincla recusantum et sera sub nocte rudentum,

saetigerique sues atque in praesaepibus ursi

saevire ac formae magnorum ululare luporum,

quos hominum ex facie dea saeva potentibus herbis

induerat Circe in voltus ac terga ferarum.

Quae ne monstra pii paterentur talia Troes

delati in portus neu litora dira subirent,

Neptunus ventis implevit vela secundis

atque fugam dedit et praeter vada fervida vexit. [Aeneid, 7:5-24]

What I love about this passage is its gorgeous uncanny quality. Here’s my stab at a line-by-line Englishing of it:

So pious Aeneas, having performed those last rites,

and smoothed the mound over the grave, as a hush

lies over the high seas, unfurls his sails and leaves the harbour.

Breezes blow through the night, white light speeds them on

a gift of the Moon, the sea glitters with a tremulous radiance.

Soon they are skirting the shoreline of Circe’s land,

where the rich daughter of the Sun makes

her untrodden groves echo with ceaseless song;

nightlong her shining palace is sweet with burning cedarwood,

as she drives her shuttle, weaving delicate textiles.

And from far away you can hear angry lions

chafing at their fetters and roaring in the deep night,

and bears and bristle-backed hogs in their pens,

raging, and huge-bodied wolves howling aloud;

these are men who, eating her magical herbs,

the deadly divine Circe had disfashioned into beasts.

To save the good Trojans from so hideous a change,

prevent them from stopping on those ominous shores,

Neptune fills their sails with favourable winds,

and hurries them, sweeping them past the seething shallows.

Inadequate as this translation is, it gives some indication of the quality, the vibe, of alluring-terrifying otherness in Vergil’s verse. The eerie calls of the magically bestialised men, resounding over the moonlit sea; a yearning and strangeness in the very heart of things. Sunt lacrimae rerum is one of the most famous of Vergilian tags, but Vergil’s great poem has always struck me as much more about strangeness than sorrow. It understands, on a deep level, how strange it is that newness comes into the world at all: how empires are created anew out of their fall; how widowers, though wholly dedicated to the memory of their beloved wives, nonetheless fall in love again, marry again, have new children. How strange it is that death, which really ought by definition to be the end of things, somehow—isn’t. The Latin novitas means both ‘novelty, newness, freshness’ and also ‘strangeness’, and Aeneas’s Roman Troynovant—another name for the Smoke, of course—is as much Strange-Troy as it is ‘Troy renewed’. More, this is for Vergil all bound up with his apprehension of the unfathomable ways divinity interacts with the mundane and the mortal. The strange ways it manifests, the stranger fact that it manifests at all (this also obsessed Graham Greene: a good half of his novels are about what Brighton Rock calls ‘the appalling strangeness of the mercy of God’).

I’m not really comparing Ings and Vergil here, despite this blogpost’s title. That would be a pretty invidious move, in and of itself; although it’s also true to say that the two approach this matter in quite different ways. Ings outlines, in his various bizarre pseudo-scientific processes and artefacts, a surreal objective correlative for his theme that in turn tends to objectify, or even reify, his strangenesses. Maybe that’s part of his integral sciencefiction-ness. For Vergil, though, the strangess of things is a fundamentally spiritual fact of existence, even if that spirit remains a numinous opacity to those of us struggling through our mortal lives.

Nick Hubble in Strange Horizons, 19 August 2019

The key unwritten law for travelling on the London Underground is that you should never interact with fellow passengers, with the possible exception of offering your seat to someone visibly more in need of it. You may, however, people-watch a bit more openly than is usually advisable on the street. At peak times, the proximity of bodies, odours, and hormones leads to a suffused comingling of fear and desire, as the drives of the collective unconsciousness rise uncomfortably close to the surface.

Towards the end of The Smoke, there is a scene in which the protagonist of the mainly first- but sometimes second-person narration, Stuart Lanyon, undergoes the full Tube experience in one unbroken swoop of transformation. Looking up from a newspaper he finds on the seat, he notices a shaven-headed young builder standing, holding on to a pole by the door. This man looks so tired that Stuart considers offering him his seat, but then becomes absorbed in contemplation of the man’s “powerful hands,” and the thought of his fingers “trembling, swollen with blood.” Allowing his gaze to move first slowly up the man’s arm and over the body beneath the fabric of his jersey, then on past his “strong chin,” Stuart suddenly finds himself locked in to eye contact:

Your breath catches in your throat. Are you afraid? Why are you afraid? Look: the man is smiling. Such a burst of liquid warmth under your skin! You want to leave your seat, not to give it up for the man, but so that you can stand beside him, bathing in the light cast by his smile. To be any distance at all from that smile, even a few feet, is unbearable. (p. 266)

However, before Stuart can rise fully to his feet, the young builder becomes caught up in a slow-motion ballet of desire with the young student and the Indian businessman who are also standing beside him by the Tube door, as the three come together in a single, sweeping embrace:

You have to join them. You have to. But you can’t, the woman next to you has her hand on your thigh, her grip is like a vice, and her other hand is between her legs, lifting her skirts, revealing the smooth, full black flesh of her thighs, and even as you lean into her, toppling into her lap, the whole carriage gives a sickening lurch, and the blind black windows, caught in mid-tunnel, erupt suddenly with colour and motion. (p. 268)

This sudden eruption unspools like an accelerated version of Gary Ross’s 1998 film, Pleasantville, in which a 1950s Midwest town is released from black-and-white conformity by the spread of colourful sexuality. A similar but more profound and revolutionary transition is happening here in Ings’s London, which—despite the obvious contemporary markers of the Tube scene described above—has in part the feel of the repressed city of the immediate postwar decades, its walls adorned with peeling posters of British stars from that period such as Hattie Jacques, James Robertson Justice, and Dirk Bogarde. It is almost as though the 2016 Brexit-voters’ wish to return Britain to the past in order “to get our country back … to the way it was before” has been realised in full, glorious monochrome. However, rather than fulfilling the demands of nostalgia, Ings’s period markers have the uncanny effect of representing the Britain of the postwar decades as a fading dream, or a pocket universe slowly blinking out of existence.

This abrupt intrusion of sexual desire into an atrophying world is due to thousands of “chickies” racing past the carriage as they flee London in the face of an imminent attack. When we first encounter the chickies in the Yorkshire hills above Stuart’s native town of Huddersfield, they appear to be primitive humanoids, capable of making items such as the corn dolly that Stuart finds as a boy, when out with his older brother, Jim. The dolly has the effect of sexually arousing Jim and, after he has hidden it beneath his pillow, leads to his first experience of masturbation. We are told this story as a flashback triggered by the adult Jim’s picking up of the dolly from his childhood bedroom, as he prepares to return to London after a brief spell staying with his father. However, the final act of his childhood memory is his destruction of the dolly after washing himself clean in the outside privy. “How can that be?” the narrative asks us before continuing:

It must be a replacement.

From where, though? They none of them last more than a few months.

Let’s say you bought this one in London from a shop east of Charing Cross Road.

You have no memory of this.

And then (I’m good at this) you do. (p. 39)

So we know from early on that the second-person narrator is manipulating Stuart’s consciousness; but it is only much later, in the immediate aftermath of the Tube scene, that it occurs to Stuart that the chickies might be manipulating everyone, and doing so well beyond simply triggering a physical sexual response. While this is indeed actually happening, the specific relationship of the chickies to Stuart is both simpler than this and yet more unexpected, requiring us to rethink the perspective from which we are reading the book. I don’t want to give the ending away entirely; but, because The Smoke is a complex and overdetermined novel, it is necessary to discuss this perspective because otherwise a plot summary leaves it open to misinterpretation. In effect, the novel is being narrated from the perspective of one particular chickie, who acts out of love as a kind of guardian angel for Stuart. What the chickie tries to save Stuart from are the potentially toxic consequences of masculinity: the cycle by which Stuart wants to be like his brother and his friends, who in turn want to be like the men they see in military posters—and therefore engage in violent and destructive acts while suppressing the capacity to feel.

In an interview with The Fantasy Hive, Ings explains how the chickies originated as part of an earlier version of the novel focused on gender:

One of the versions of the story was about gender invention. It was going to be a society in which only men existed, so femininity had to be manufactured. […] So the chickies were a desire to create a non-binary target for human desire. And of course the consequence is because they’re a target for desire no one really thinks about what they’re doing. And, without giving too much away, they’re kind of important, and nobody knows it. […] The chickies were the last vestige of the version of the story that was about the construction of gender, so it’s a little bit of archaeological material left in the book, but I was able to make it work in the end, for the purposes of the final version.

There is perhaps more “archaeological material” left in the final novel than Ings suggests, because it is noticeable that it is still principally constructed around three male-female relationships: between Stuart’s father and mother; between Stuart’s aunt, Stella, and the Bundist, Georgy Chernoy; and between Stuart and Georgy’s daughter, Fel. All are estranged by the particular circumstances envisaged in Ings’s alternate history. The fact that The Smoke is set in a world in which North America has effectively disappeared, following the “Yellowstone eruption” of 1874 and a subsequent ten-year global winter, is not without significance: it means that the British Empire is the dominant world power. But the main differences between Ings’s world and ours result from the invention of the Gurwitsch ray.

Alexander Gurwitsch was a real-life Russian biologist and biochemist who is best known for discovering biophotons—photons of light produced by biological systems. In The Smoke, Gurwitsch develops a biophotonic ray that he claims has healing properties and can guide foetal development in order to sculpt organic life. The ray is used in the winter of 1916-17 by the Kaiser Wilhelm Society to treat the dead and dying troops on the battlefield of the Somme; the following spring, a horde of diminutive needle-toothed creatures, the chickies, emerge—and survive by feeding on the dead. In response, Europe succumbs to an existential horror of pogroms against all the usual forms of the other; but this has little negative effect on the chickies themselves. The subsequent attempt by German industry to use the chickies as “subhuman” industrial labour is undermined by their capacity to promote a sexual response in humans. We are told that the German economy was bankrupted in 1937 by the participation of the entire Ruhr Valley workforce in a summer-long orgy, and it is plain that this event averted the threat of a second world war. By the end of the novel, we understand that the chickies are not just some sort of manifestation of a return of the repressed, but a telepathic species who are trying to intervene in and thereby transform the gendered sexual violence of male human beings.

There is another key alternate-historical development in the novel. As a result of the 1917 pogroms, the remnants of the Jewish Labor Bund, a Marxist secular organisation, flee to Moscow before accepting Lenin’s offer of Birobidzhan in Siberia as a homeland. Here, they go on to make history in the space of thirty years because they have the Gurwitsch ray:

Gurwitsched wheat averted the ’21 famine, saving Saint Petersburg. Gurwitsched horses twenty-five hands high pulled rocks out of the path of the White Sea Canal, connecting the Arctic to the Baltic. All Europe fed on Gurwitsched pigs, Gurwitsched apples, Gurwitsched lemons. Until at last their mastery was such, the Bundists dared to try again, and in a much more careful, targeted fashion, what had been tried in 1917. They turned the rays upon themselves. (p. 51)

The result is that the Bundists become technologically advanced transhumans who, we are told through the chickie’s second-person narration, have by the time of the novel’s present, shaped all the world’s big cities. The back story of Stuart’s training as an architect allows Ings to map out how the Bund’s use of 3-D printing techniques revolutionises construction and contributes to the radical transformation of London’s built environment and skyline with “great shining towers of plastic stuff, all glass curtain walls and weather-responsive bricks.” On the one hand, this is an ingenious fictional version of the transformation of London in recent years: think iconic skyscrapers, from the Gherkin to the Shard. On the other hand, it is seriously disturbing, for all the chickie’s assurance that no one “talks about ‘enclaves’ any longer, far less ‘ghettos’” (p. 21). The racial othering of financial and technological development as semi-alien Jewishness is uncomfortable for the reader, especially given recent concerns over antisemitism in public life in Britain.

So what is going on here? On one level, Ings is clearly trying to discomfort the reader. In the Fantasy Hive interview he admits: “You want to get hold of the readers of the two star reviews and shake them. ‘I did that on purpose to wind you up!’” He is actually talking specifically about his inclusion of a scene in which Stuart can’t figure out how to use a smartphone, but the wider point behind that is to skewer a specifically British resistance to social change, technology, and alterity—values that can be dismissed as belonging to “unBritish metropolitan liberals”—that dates back to the postwar decades. If Ings was merely transposing the antisemitic attitudes of 1950s and 1960s Britain—even as part of an obvious pastiche—to our contemporary global context in order to discomfort or provoke us, it would be highly problematic. Satire or playful context is no justification for circulating time-old negative tropes. However, I think Ings is doing something more subtle than this.

The chickie’s second-person narration of Stuart’s attitude to the Bund functions to chide, or even goad, both him and the reader to either overcome or honestly admit this resistance, and the related structural failure to accept otherness. This is close to the bone at times, as when the chickie suggests Stuart’s thoughts: “The Bund’s in every country now, with enclaves in all big cities. The obvious metaphor for this process—a tumour metastasising—fails because of its unkindness” (p. 52). Yet because of the complex structure of the novel we are always aware that the narration is mediated and that Stuart’s inability to overcome his resistance to Fel, even as he is overwhelmed by both desire for her and the desire to be like her, has blighted his life. There is further the question of whether the chickie is motivated by their own resistance to Fel, and jealousy over her relationship with Stuart. Ultimately, The Smoke is a novel that addresses the complexity of personal and political relationships in our world, which has been marking time since 1917, by fictionalising the development of a form of socialist alterity. Whether Ings had to make the Jewish Bund the proponents of this socialism is open to question, but there is some historical logic to this and there is never any doubt that the sympathies of the novel lie with the prospect of a transformed future overcoming the legacies of the imperial past.

As mentioned above, one of the key features of Ings’s alternate history is that, in a world with no America and in which no Second World War has happened, Britain remains—at least in conventional terms—the pre-eminent global power and committed to a full-blooded imperialism. However, the global spread and technological advances of the Bund have called into question the real extent of British hegemony and so triggered a reaction. Accordingly, The Smoke opens with an account of the preparations in the Australian desert (still British territory) for the launch of the nuclear-bomb-powered, Union-Jack-emblazoned HMS Victory—including Stuart’s brother as one of its crew—on what turns out to be an ill-fated spaceflight to the Moon, Mars, Jupiter, and beyond. By establishing territorial domination in Space, the British intend to reassert their mastery: a mastery that is equated with superiority over others and a straight-laced masculinity—reflected by the choice of Lanyon, with its intertextual connection to one of the characters in Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, as Stuart’s surname.

From the perspective of Stuart and Bob, everyone else in the novel is othered—and not just the Bundists, who clearly represent a group that can be openly joined. By having the Lanyons come from Huddersfield, one of the former hubs of the industrial revolution, once again booming with “spaceship yards and bomb manufactories” (p. 20), Ings is able to critique some of the founding myths of contemporary Britishness. The industries might be unfamiliar, but the northern experience represented by Stuart’s trip with his dad, Bob, for fish and chips by the canal—and then on for five pints in the pub—is straight out of postwar British kitchen-sink drama. For all the work, however, no one seems to be happy, and resentment is directed, as in the real-world north of England in 2019, squarely at the perfidious southern world of London. Later, Stuart is attacked despite his local roots simply, he suspects, for having “the temerity to leave town in the first place, head for the capital, scholarship under my arm, to better myself” (p. 244). Calling the novel The Smoke highlights the ever-increasing incongruity of London’s nickname, as its slick high-rise developments and financial growth take it further and further away from everyday life in the industrial north. There is no British common culture of the type claimed by postwar British intellectuals, and to pretend there is avoids the choices which would otherwise have to be made. Like Jekyll, Stuart comes to realise that he can’t keep the two worlds he lives in apart and that he needs to choose between the working-class way of life represented by his dad or the transformed, and implicitly feminised, future represented by Fel.

The incompatibility of the two, and what is at stake in the choice between them, is neatly encapsulated in Stuart’s recollection of Bob’s trip south to visit them in Fel’s flat a few years before the novel’s present:

He might have been visiting a fairy’s castle. The place astounded him: its size, its light. It was only a flat on the Barbican Estate. A self-igniting hob. An electric piano. Tablets. A phone without a chord. Nobody he knew owned such things as he saw there. (p. 19)

The standard trappings of late capitalist modernity are here estranged, and thus revealed to us afresh as the product of a form of magic which is utterly alien to the supposed common ways of life underpinning Britishness as a shared identity. For much of the long twentieth century, this fault line ran through individual experience as technology—the car, the telephone, the washing machine, the television—slowly opened up the possibility of not just changed forms of behaviour but also, more significantly, led to a divergence of social values from the traditional patterns of morality, respectability, and deference.

In our own world, the British EU referendum of 2016 saw an eruption into the open of what had by then become a radical binary opposition between incompatible belief-sets. This revealed a nation divided from itself. In The Smoke, Ings represents this division by overlapping it with a divide between British men, such as Stuart, his brother and father, and everyone else, such as Fel, and Stuart’s mother and aunt. Stella, for example, represents that recognisable postwar British phenomenon of the girl who escapes the working-class streets of her youth through success on screen and stage. It is her beauty and celebrity status that take her into a relationship with Georgy and subsequently bring Stuart and Fel together. However, one of the pivotal moments of the novel is the description of how Stuart’s mother, Betty, who had previously seemed the stereotypical stay-at-home sister, undergoes the “Chernoy Process”—developed by Georgy—by which she gives birth to a regenerated transhuman version of herself.

These familial and social divides converge in a disastrous dinner party hosted by Stella and Georgy on Christmas Eve, which takes place without any Christmas trappings (much to Stuart’s disappointment). When the conversation moves from the impending Mars-bound departure of Jim on the Victory, to whether the Bundists could use their birth technologies on the moon, Georgy responds:

“Quite why everyone is so fascinated by the population curves of the Jewish race, I’ll never know. It has always been like this. As if we’re a sort of human isotope. Don’t let them reach critical mass!” (p. 166)

Tellingly, this “defensiveness” irritates Stuart, who wonders why Georgy is referring to his community by “the old unhappy name,” when all acknowledge the Bundists as the triumphant modern and materialist figure to emerge from the Great War, “crushing the rabbi under his proletarian heel.” Here Stuart manifests several different levels of bad faith. The latent hostility of British society to the Bundists, of which he is not immune himself, is evident throughout the text, and his annoyance at Georgy’s direct acknowledgment of antisemitism is characteristic of how members of a dominant culture resent having their structural biases exposed. Moreover, in criticising Georgy for not being consistent in his socialist modernity, Stuart is implicitly voicing his own mixed feelings about the level of change it requires to move from proletarian roots to a transformed future. It is this ambiguity that undermines his relationship with Fel; and yet Stuart evades this hard truth, too, by denying his own unwillingness to commit—instead ascribing their break-up to her difference from him. He takes refuge in characterising their relationship as that between a “native” informant and an ethnographer. By seeking to avoid responsibility for his own shortcomings, Stuart in effect aligns himself with the British Empire and his brother’s participation in the Mars mission intended to establish dominance over the Bundists from space. Ings’s discomforting of the reader through identifying the Bundists as the agents of transhuman progress thereby forces them to face the racism, antisemitism, and resistance to otherness implicit in the characteristically male-British moral evasions that Stuart personifies.

Despite the fact that Ings manages to effect some sort of resolution before the end of the novel—through a superbly weird scene bringing Stuart, Fel, and the chickie together—The Smoke’s strange blend of gender politics, British social realism, alternate history, and futuristic technology does not dovetail into a neatly unified whole. Nethertheless, the overdetermined, messy feel of the text, filtered in parts through the chickie’s second-person narration, conveys a picture of British life that seems emotionally true. When we look back on the chaos of the late 2010s—perhaps from an extraterrestrial transhuman vantage point—this will be one of the few novels that will communicate to our altered descendants the full limitations of the culture they have left behind. Ings has covered similar endgame territory to varying degrees in the past, most recently in Wolves (2014), which Martin Petto described in his review for Strange Horizons “as a fascinating work of transition,” and on the road to having the same kind of sustained contemporary relevance as M. John Harrison’s work. Following the publication of The Smoke, I think we can safely say that Ings has reached that destination. It is a subtle and sophisticated work of fiction that combines emotional power with intellectual depth to produce a novel with the power to transfigure the tawdry world surrounding us in Britain.

While there are plenty of writers who excel at depicting the claustrophobic interactions between social class, sexual repression, and unsatisfactory personal relationships which characterise the British psyche, I don’t think anyone has previously managed so well to capture the full humiliating awfulness of what it feels like to be trapped within this backward-looking, jingoistic, introverted culture while it lurches drunkenly forward, trousers round ankles, slap-bang into the relentlessly onrushing future of climate catastrophe, technological singularity, post-binary genders, and transhumanism. Like Stuart, we’ve reached the point of no return—and the hard choices can no longer be avoided.

David Pitt, Booklist

Ings isn’t one of those SF writers who explains in great detail how his fictional world came to be. Rather, he drops a hint here, a tantalizing bit of dialogue there, and the resulting sense of uncertainty actually adds a layer of suspense to the story. His fictional world—an earth that followed a different historical path from our own—is beautifully constructed, with three different human subspecies, and around that world, he builds a wildly complex and decidedly surreal plot that concerns an alternate UK in which the primary narrator, an architect from Yorkshire, is drawn into a high-tech global crisis stemming from the fracturing of humanity into those three subspecies. Meanwhile, the narrator, often speaking in the second person, must deal with a range of realistically rendered domestic issues typical of mainstream fiction. In all, it’s a wonderfully imaginative story, the sort of thing Adam Roberts might write, or perhaps Christopher Priest: stories about history that didn’t happen but feels oddly like it did, and characters who are very different from us but at the same time very familiar. For those who don’t mind if their alternate worlds are liberally dosed with surrealism, this is likely to be a very special book.

In The Smoke, Simon Ings takes familiar science fiction ingredients – alternate history, immortality, genetic manipulation/mutation, space exploration and body swapping – and bakes a magnificent, albeit utterly insane, cake.

Ian Mond

The Smoke is genre, and was published by a genre imprint, but it’s not a book that invites easy description. It does some things I don’t think I’ve seen genre novels do before, and it crashes together ideas that really shouldn’t work on their own, never mind side by side.

Ian Sales

Beautifully and evocatively written, The Smoke is a thrilling thought-experiment in social schisms, technology and the ethics of immortality.

Liz Jensen, author of The Ninth Life of Louis Drax

The Smoke is a stunning, clever and wildly original book: an exquisite sci fi fantasy and a lucid meditation on the nature of humanity and the mortal self. Simon Ings has confirmed his reputation as one of the most philosophically brilliant and imaginative writers around.

Joanna Kavenna, author of The Birth of Love

Astonishing, gripping, horrifying, redemptive, The Smoke sizzles with intelligence and heart.

Michael Blumlein

So many strong ideas here drift from hard sf extrapolation into alluring strangeness: a triumph of the weird.

Matthew de Abaitua, author of Self & I

A mindblowing exploration of a parallel present but also, at root, an exploration of love.

Will Ashon

Literary agent and provocateur John Brockman has turned popular science into a sort of modern shamanism, packaged non-fiction into gobbets of smart thinking, made stars of unlikely writers and continues to direct, deepen and contribute to some of the most hotly contested conversations in civic life.

This Idea Is Brilliant is the latest of Brockman’s annual anthologies drawn from edge.org, his website and shop window. It is one of the stronger books in the series. It is also one of the more troubling, addressing, informing and entertaining a public that has recently become extraordinarily confused about truth and falsehood, fact and knowledge.

Edge.org’s purpose has always been to collide scientists, business people and public intellectuals in fruitful ways. This year, the mix in the anthology leans towards the cognitive sciences, philosophy and the “freakonomic” end of the non-fiction bookshelf. It is a good time to return to basics: to ask how we know what we know, what role rationality plays in knowing, what tech does to help and hinder that knowing, and, frankly, whether in our hunger to democratise knowledge we have built a primrose-lined digital path straight to post-truth perdition.

Many contributors, biting the bullet, reckon so. Measuring the decline in the art of conversation against the rise of social media, anthropologist Nina Jablonski fears that “people are opting for leaner modes of communication because they’ve been socialized inadequately in richer ones”.

Meanwhile, an applied mathematician, Coco Krumme, turning the pages of Jorge Luis Borges’s short story The Lottery in Babylon, conceptualises the way our relationship with local and national government is being automated to the point where fixing wayward algorithms involves the applications of yet more algorithms. In this way, civic life becomes opaque and arbitrary: a lottery. “To combat digital distraction, they’d throttle email on Sundays and build apps for meditation,” Krumme writes. “Instead of recommender systems that reveal what you most want to hear, they’d inject a set of countervailing views. The irony is that these manufactured gestures only intensify the hold of a Babylonian lottery.”

Of course, IT wasn’t created on a whim. It is a cognitive prosthesis for significant shortfalls in the way we think. Psychologist Adam Waytz cuts to the heart of this in his essay “The illusion of explanatory depth” – a phrase describing how people “feel they understand the world with far greater detail, coherence and depth than they really do”.

Humility is a watchword here. If our thinking has holes in it, if we forget, misconstrue, misinterpret or persist in false belief, if we care more for the social consequences of our beliefs than their accuracy, and if we suppress our appetite for innovation in times of crisis (all subjects of separate essays here), there are consequences. Why on earth would we imagine we can build machines that don’t reflect our own biases, or don’t – in a ham-fisted effort to correct for them – create ones of their own we can barely spot, let alone fix?

Neuroscientist Sam Harris is one of several here who, searching for a solution to the “truthiness” crisis, simply appeals to basic decency. We must, he argues, be willing to be seen to change our minds: “Wherever we look, we find otherwise sane men and women making extraordinary efforts to avoid changing [them].”

He has a point. Though our cognitive biases, shortfalls and the like make us less than ideal rational agents, evolution has equipped us with social capacities that, smartly handled, run rings round the “cleverest” algorithm.

Let psychologist Abigail Marsh have the last word: “We have our flaws… but we can also claim to be the species shaped by evolution to possess the most open hearts and the greatest proclivity for caring on Earth.” This may, when all’s said and done, have to be enough.

Visiting the Transmediale festival in Berlin for New Scientist, 21 February 2018

BERLIN’S festival of art and media culture Transmediale is an annual reminder that art is more than a luxury good. It gives us the words, images and ideas we need to talk to each other about a changing world.

Big social changes involve big shifts in how art is made and consumed. It is a nerve-racking process for artists, who can have no idea, as they embark on their ventures, whether the public will come to appreciate and enjoy their work. And at this year’s Transmediale, the chickens came home to roost.

To begin at the beginning, back in the 1950s, Andy Warhol and the pop art movement looked at the world through the prism of advertising hoardings and television. A new generation of artists has been making art out of the internet.

Some artists have attempted to imagine the internet itself, paying attention to developments in data management and artificial intelligence, so they can better imagine what the internet is and what it might become.

The performance premiering at the festival this year, James Ferraro’s Dante-esquePlague, was work of this sort: a credible, visceral and downright terrifying portrayal of consciousness emerging from the audio-visual detritus of social media.

Other artists have used the internet as a tool through which to look at the world. Much of this work resembles anthropology more than art. Take Lisa Rave’s film Europium, which flits between trading floors, TV showrooms and a wedding ceremony in Papua New Guinea to trace the material connections and cultural gulfs that distinguish different kinds of money, from seashell dowries to plastic banknotes. In so doing, she constructs a microhistory of the rare element europium that wouldn’t look out of place in a high-end magazine, and brings the hackneyed link between capitalism and colonialism to life.

But there is a problem: artists working with the materials of the internet are further removed from physical reality than their forebears. They are looking at the world through what is, really, a single, totalising, bureaucratic machine. (It’s called the World Wide Web for a reason.) And in art, as in life, you are what you eat.

The internet sorts. It archives. Many of its artists are, in consequence, good little bureaucrats who offer “findings”, “research” and “presentations” (at Transmediale we even had an “actualisation”, from artist and gay activist Zach Blas), but rarely anything as trite as finished work.

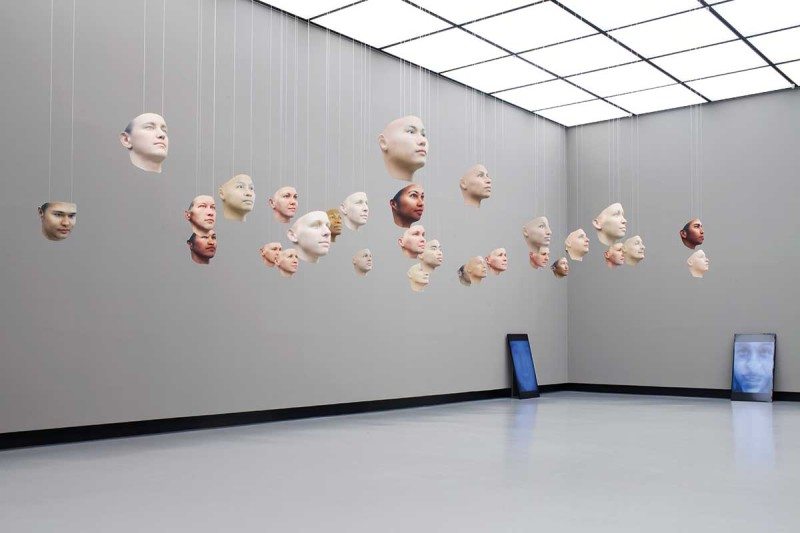

Nothing ages on the internet; nothing dies. Nothing is ever resolved. Similarly with its art: Heather Dewey-Hagborg’s A Becoming Resemblance, which uses DNA from Chelsea Manning, the former US soldier who leaked classified documents, is to all intents and purposes a brand new piece, but it is still presented as a fragment of a work begun in 2015.

Does the open-endedness of this art make it bad? Of course not. But internet art hardly ever gets finished. There’s always more data to sort, a virtual infinitude of rabbit holes to hurl yourself down, and very little that is genuinely new has had a chance to emerge. I defy a newcomer to tell the difference between the work premiering here and work that is 20 years old.

The field has, as a consequence, turned into the art world’s Peter Pan: the child that never grew up. And we treat it as a child. We tiptoe around anything resembling a negative opinion, as though every time one of us said, “I don’t believe this piece is any good”, a video artist somewhere would fall down dead.

In other words, the world of media art has suffered the same fate that has befallen the rest of the internet-enabled planet. The very technology that promised us the world on a screen has been steadily filtering out the challenges and contrary opinions that made our interests and ideas so vital in the first place, leaving us living in an echo chamber.

It was Lioudmila Voropai, a Ukrainian art historian, who got the gathered artists, curators and academics at Transmediale to confront some chilly realities about their field. We knew the book she was launching contained dynamite because it was entitled Media Art as a By-Product – no punches pulled there. Another reason was that she spent all her time telling us what her book didn’t do. It didn’t criticise. It didn’t take a political position. It asked a few questions. It didn’t have answers. Nothing to see here.

Finally someone piped up: “So the media art we’ve come here to enjoy and talk about and theorise over actually exists only to sustain museums of media art? Is that what you’re saying?”

And Voropai, perhaps figuring that she may as well be hung for a sheep as a lamb, let rip: “The extraordinary thing about media art,” she said, “is that the moment it was institutionally established, it was declared conceptually obsolete.”

This was only the beginning. Speaker after speaker made sincere efforts to get the left-wing, countercultural, transgressive Transmediale participants to look at themselves in the mirror. It took courage to try to get media artists to admit that their radical chic has been stolen by the likes of the just-as-countercultural far-right Breitbart News Network; that they have forgotten (as right-wingers like Donald Trump have not) how to entertain; and that they exist chiefly to sustain the institutions that fund them. These efforts were received with seriousness and courtesy.

Attempts to puncture the “new media art” bubble from the inside might have seemed a bit laughable to outsiders. Occupying most of the venue’s impressive foyer, Hate Library was a printout of the results (pictured left) artist Nick Thurston obtained when he typed “truth” into the search box on the online bulletin board of the white-supremacist Stormfront Europe group. The idea, I think, was to confront the Transmediale crowd with the big, bad world outside. But to the rest of us, this felt like old news. If you go there, and type that, surely you get what you deserve?

Even so, I am inclined to admire people who take their social and artistic responsibilities seriously enough to ask uncomfortable questions of themselves, and risk a bit of awkwardness and ridicule along the way.

After all, much of this work does get under your skin. It does make you look at the world anew. As I was leaving, I looked in at Yuri Pattison’s installation Vitra Alcove (some border thoughts). Pattison has mashed up videogame-generated coastal cities and garbled news tickers to capture the queasy liquidity of mediated life.

Sitting there, bombarded by algorithmically generated fake news and dizzy from the image blizzard, I was reminded of the few fraught days I once spent sitting among New Scientist‘s news team as it fished for real stories in a web-borne ocean of alarmism, self-promotion and misinterpretation. Pattison’s work says at least as much about my life as L. S. Lowry’s paintings of matchstalk men and cats and dogs said about my grandfather’s.

In January 2015, Eric Schmidt, then executive chairman of Google, declared that the internet was destined to disappear. He was talking about the internet of things: how the infrastructure that is beginning to weave together the materials and objects of daily life would burrow its way into our lives, and so become invisible.

But if, in the act of becoming ubiquitous, the internet also disappears, then our lives will be held hostage by a bureaucratic infrastructure we can no longer see, never mind control. Media art explores and shines strong light onto this complacent, hyper-conformist, not-so-brave world. Of course the art is strange, hard to explain – and a work in progress. How could it not be? That is its job.

Visiting the Royal College of Physicians for New Scientist, 17 February 2018

AFFECTION and delight aren’t qualities you would immediately associate with an exhibition about blood flow. But Ceaseless Motion reaches beyond the science to celebrate the man – 17th-century physician William Harvey – who, the story goes, invented the tradition of doctors’ bad handwriting. He was also a benefactor: when founding a lecture series in his own name, he remembered to bequeath money for the provision of refreshments.

It is an exhibition conceived, organised and hosted by the UK’s Royal College of Physicians, whose 17th-century librarian Christopher Merrett described how to make champagne several years before the monk Dom Pérignon began his experiments. Less happily, Merrett went on a drinking binge in 1666, and let Harvey’s huge book collection burn in London’s Great Fire.

The documents, seals and signatures that survived the flames despite Merrett’s neglect take pride of place in an exhibition that, within a very little compass, tells the story of one of medicine’s more important revolutionaries through documents, portraits and some deceptively chatty wall information.

Before Harvey’s 10 years of intense, solitary study bore fruit, physicians thought blood was manufactured in the liver and then passed through the body under its own volumetric pressure. Heaven help you if you made too much of the stuff. Luckily, physicians were on hand to release this disease-inducing pressure through bloodletting.

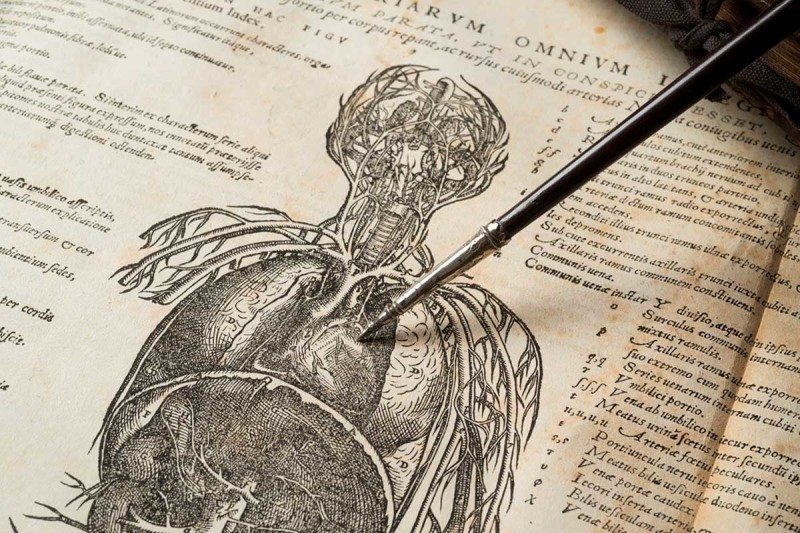

It sounds daft now, but clues back then that something quite different was going on were sparse and controversial. The 16th-century physician Andreas Vesalius had puzzled over the heart. If, like every other organ, it fed on blood produced in the liver, why were its walls so impenetrably hard? But even this towering figure, the founder of modern anatomy, decided that his own observations had to be wrong.

It was Hieronymus Fabricius, Harvey’s teacher in Padua, Italy, who offered a new and fruitful tack when he mapped “the little doors in the veins” that, we know now, are valves maintaining the flow of blood back to the lungs.

Within 30 years, Harvey’s realisation that blood pressure is controlled by the heart, and that this organ actively pumps blood around the body in a continuous circuit, had overturned the teachings of the 2nd-century Graeco-Roman physician Claudius Galen in European centres of learning. The new thinking also put close clinical observation at the heart of a discipline that had traditionally spent more time on textual analysis than on examining patients.

The exhibition is housed in a building designed by Denys Lasdun. This celebrated modernist architect was so taken by Harvey’s achievements that he designed the interiors as a subtle homage to the human circulatory system.

With the royal college now celebrating its 500th birthday, its institutional pride is palpable, but never stuffy. As one staff member told me, “We only started talking about ourselves as a ‘Royal’ college after the Restoration, to suck up to the king.”

Those who can visit should be brave and explore. Upstairs, there are wooden panels from Padua with the dried and salted circulatory and nervous systems of executed criminals lacquered into them. They are rare survivors: when pickling methods improved and it was possible to provide medical students with three-dimensional teaching aids, such “anatomical plates” were discarded.

Downstairs, there are endless curiosities. The long sticks doctors carried in 18th-century caricatures were clinical instruments – latex gloves didn’t arrive until 1889. The sticks’ silver ferrules contained miasma-defeating herbs and, sometimes, phials of alcohol. None of them are as handsome as Harvey’s own demonstration rod.

But if a visit in person is out of the question, take a look at the royal college’s new website, launched to celebrate half a millennium of institutional conviviality and controversy. You will have to provide your own biscuits, though.

Visiting 😹 LMAO at London’s Open Data Institute for New Scientist, 2 February 2018

On Friday 12 January 2018, curators Julie Freeman and Hannah Redler Hawes left work at London’s Open Data Institute confident that, come Monday morning, there would be at least a few packets of crisps in the office.

Artist Ellie Harrison‘s Vending Machine (2009; pictured below) sits in the ODI’s kitchen, one of the more venerable exhibits to have been acquired over the institute’s five-year programme celebrating data as culture. It has been hacked to dispense a packet of salty snacks whenever the BBC’s RSS feed carries a news item containing financial misfortune.

No one could have guessed that, come 7 am on Monday morning, Carillion, the UK government’s giant services contractor, would have gone into liquidation. There were so many packets in the hopper, no one could open the door, say staff.

Such apparently silly anecdotes are the stuff of this year’s show, the fifth in the ODI’s annual exhibition series “Data as Culture”. This year, humour and absurdity are being harnessed to ask big questions about internet culture, privacy and artificial intelligence.

Looking at the world through algorithmic lenses may bring occasional insight, but what really matters here are the pratfalls as, time and again, our machines misconstrue a world they cannot possibly comprehend.

In 2017, artist Pip Thornton fed famous poems to Google’s online advertising service, Google AdWords, and printed the monetised results on till receipts. The framed results value the word “cloud” (as in I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud by William Wordsworth) highly, at £4.73, presumably because Google’s algorithm was dreaming of internet servers. It had no time at all for Wilfred Owen: “Froth-corrupted” (Dulce et Decorum Est) earned exactly £0.00.

You can, of course, reverse this game and ask what happens to people when they over-interpret machine-generated data, seeing patterns that aren’t there.

This is what Lee Montgomery has done with Stupidity Tax (2017). In an effort to understand his father’s mild but unaccountably secretive gambling habit, Montgomery has used a variety of data analysis techniques to attempt to predict the UK National Lottery. The sting in this particular tale is the installation’s associated website, which implies (mischievously, I hope) that the whole tongue-in-cheek effort has driven the artist ever so slightly mad.

Watching over the whole exhibition – literally because it’s peeking through a hole in a ceiling tile – is Franco and Eva Mattes’s Ceiling Cat, a taxidermied realisation of the internet meme, and a comment on the nature of surveillance beliefs (pictured top). “It’s cute and scary at the same time,” the artists say, “like the internet.”

Co-curator Freeman is a data artist herself. If you visited last year’s New Scientist Live you may well have seen her naked mole-rat surveillance project. The 7.5 million data points acquired by the project are now keeping network analysts busy at Queen Mary University of London. “We want to know if mole-rats make good encryption objects,” says Freeman. Their nest behaviours might generate true random numbers, handy for data security. “But the mole-rat queens are far too predictable… Crisp?”

Through a mouthful of salt and vinegar, I ask Freeman where her playfulness comes from. And as I suspected, there’s intellectual steel beneath: “Data is being constantly visualised so we can comprehend it,” she says, “and those visualisations are often done in a very short space of time, for a particular purpose, in a particular context, for a particular audience. Then they acquire this afterlife. All of a sudden, they’re the lenses we’re looking through. If you start thinking about data as something rigid and objective and bearing the weight of truth, then you’ve stopped discerning what is right and what is wrong.”

Freeman wants us to analyse data, not abandon it, and her exhibition is an act of tough love. “When we fetishise data, we end up with what’s happening in social media,” she says. “So many people drowning in metadata, pointing to pointers, and never acquiring any knowledge that’s deep and valuable. There should be some words to express that glut, that need to roll back a little bit. Here, have another crisp.”