Thanks to the recent publication of Engineers of Human Souls, I got to discuss censorship, free speech and modern China with journalist Yuan Yang and philosopher Jeffrey Howard when Rana Mitter hosted Radio 3’s Free Thinking on 19 March 2024. The programme is available on BBC Sounds.

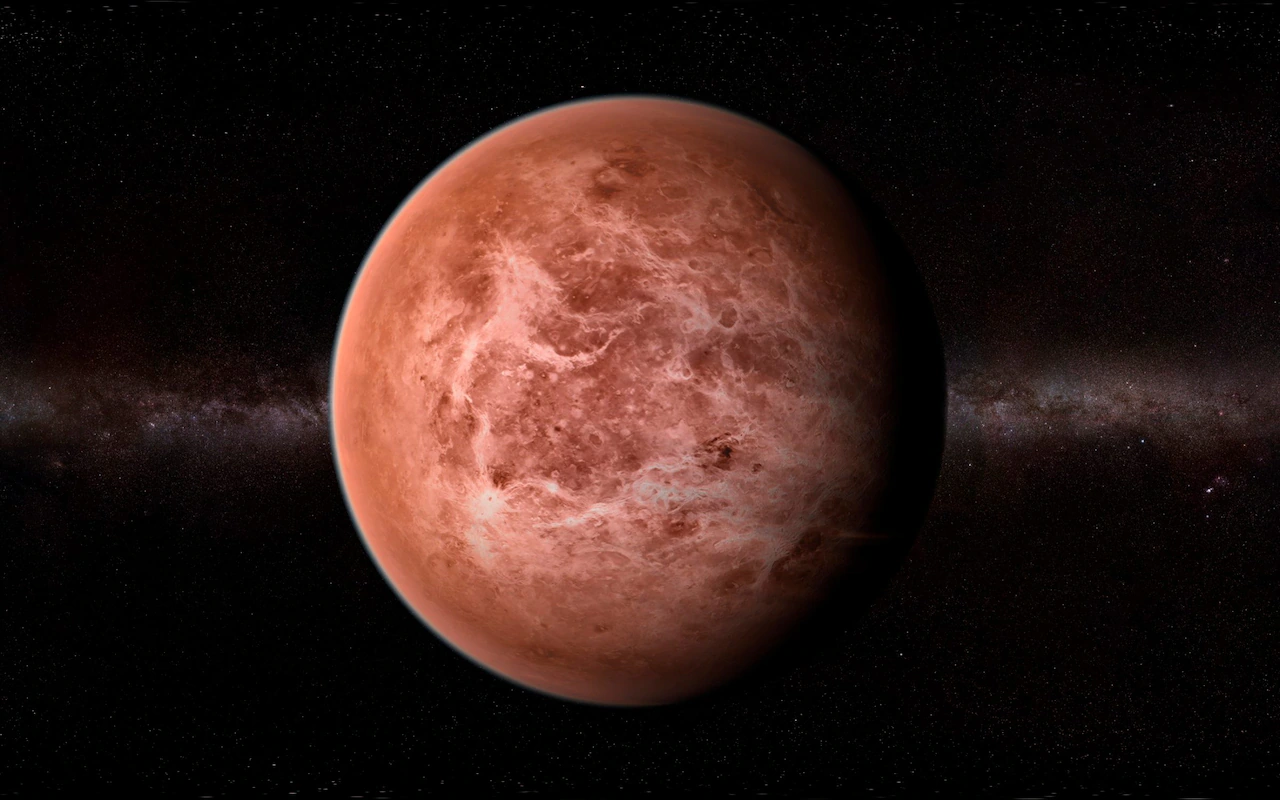

The Penguins of Venus

Reading Our Accidental Universe by Chris Lintott for the Telegraph, 8 March 2024

Phosphine — a molecule formed by one phosphorous atom and three atoms of hydrogen — is produced in bulk only (and for reasons that are obscure) in the stomachs of penguins. And yet something is producing phosphine high in the clouds of Venus — and at just the height that conditions are most like those on the surface of the Earth. Unable to land (unless they wanted to be squished and fried under Venus’s considerable atmosphere), and armoured against a ferociously acidic atmosphere, the penguins of Venus haunt the dreams of every stargazer with an ounce of poetry in their soul.

Chris Lintott is definitely one of these. An astrophysicist at Oxford University and presenter of BBC’s The Sky at Night, Lintott also co-founded Galaxy Zoo, an online crowdsourcing project where we can volunteer our time, classifying previously unseen galaxies. The world might be bigger than we can comprehend and wilder than we can understand, but Lintott reckons our species’ efforts at understanding are not so shoddy, and can and should be wildly shared.

Our Accidental Universe is his bid to seize the baton carried by great popularisers like Carl Sagan and Patrick Moore: it’s an anecdotal tour of the universe, glimpsed through eccentric observations, tantalising mysteries, and discoveries stumbled upon by happenstance.

Lintott considers the possibilities for life outside the Earth, contemplates rocks visiting from outside the solar system, peers at the night sky with eyes tuned to radio and microwaves, and shakes a fist at the primordial particle fog that will forever obscure his view of the universe’s first 380,000 years.

Imagine if we lived in some globular star cluster: that spectacular night sky of ours would offer no visible hint of the universe beyond. We might very well imagine our neighbouring stars, so near and so bright, were the sum total of creation — and would get one hell of a shock once we got around to radio astronomy.

Even easier to imagine — given the sheer amount of liquid water that’s been detected already just within our own solar system brought above freezing by tidal effects on moons orbiting gas giant planets — we might have evolved in some lightless ocean, protected from space by a kilometres-thick icecap. What would we know of the universe then? Whatever goes on in the waters of moons like icy Enceladus, it’s unlikely to involve much astronomy.

As luck would have it, though, growing up on land, on Earth, has given us a relatively unobscured view of the entire universe. Once in 1995, so as to demonstrate a fix to its wonky optics, the operators of the Hubble Space Telescope pointed their pride and joy at (apparently) nothing, and got back a picture chock-full of infant galaxies.

Science is a push-me pull-you affair in which observation inspires theory, and theory directs further observation. Right now, the night sky is turning out to be much more various than we expected. The generalised “laws” we evolved in the last century to explain planet formation and the evolution of galaxies aren’t majorly wrong; but they are being superseded by the carnival of weird, wonderful, exceptional, and even, yes, accidental discoveries we’re making, using equipment unimaginable to an earlier generation. Several techniques are discussed here, but the upcoming Square Kilometre Array (SKA) takes some beating. Sprouting across southern Africa and western Australia, this distributed radio telescope, its components strung together by supercomputers, will, says Lintott, “be sensitive to airport radar working on any planet within a few hundred light-years”.

Observing the night sky with such tools, Lintott says, will be “less like an exercise in cerebral theoretical physics and more like reading history.”

Charming fantasies of space penguins aside (and “never say never” is my motto), there’s terror and awe to be had in Lintott’s little book. We scan the night sky and can’t help but wonder if there is more life out there — and yet we have barely begun to understand what life actually is. Lintott’s descriptions of conditions on the Jovian moon Titan — where tennis ball-sized drops of methane fall from orange clouds — suggest a chemistry so complex that reactions may be able to reproduce and evolve. “Is this chemical complexity ‘life’? he asks. “I don’t know.”

Neither do I. And if they ever send me on some First Contact mission amid the stars, I’m taking a bucket of fish.

“Spectacular, ridiculous, experimental things”

Reading The Tomb of the Mili Mongga by Samuel Turvey for New Scientist, 6 March 2024

Pity the plight of evolutionary biologist Samuel Turvey, whose anecdotal accounts of fossil hunting in a cave near the village of Mahaniwa, on the Indonesian island of Sumba, include the close attentions of “huge tail-less whip scorpions with sickening flattened bodies, large spiny grabbing mouthparts, and grotesquely thin and elongated legs”.

Why was a conservation biologist hunting for fossils? Turvey’s answer has to do with the dual evolutionary nature of islands.

On the one hand, says Turvey, “life does spectacular, ridiculous, experimental things on islands, making them endlessly fascinating to students of evolution.”

New Caledonia, a fragment of ancient Gondwana, boasts bizarre aquatic conifers and even shrubby parasitic conifers without any roots. Madagascar hosts a lemur called the aye-aye; a near primate equivalent to the woodpecker. But my personal favourite, in a book full of wonders, pithily described, is the now extinct cave goat Myotragus from predator-free Majorca and Menorca. Relieved of the need to watch its back, it evolved front-facing eyes, giving it the disconcerting appearance of a person wearing a goat mask.

But there is a darker side to island life: it’s incredibly vulnerable. The biggest killers by far are visitations of fast-evolving diseases. European exploration and colonisation between the 16th and 19th centuries decimated the human populations of Pacific archipelagos, as a first wave of dysentery was followed by smallpox, measles and influenza. Animals brought on the trip proved almost as catastrophic to the environment. Contrary to cliche, westerners on the island of Mauritius did not hunt the dodo to extinction; rats did. And let’s not forget Tibbles, the cat that’s said to have single-handedly (pawedly?) wiped out the Stephens Island wren, a tiny flightless songbird, in 1894.

There are lessons to be learned here, of course, but Turvey’s at pains to point out that islands are accidents waiting to happen. Islands are by their very nature sites of extinction. They may be treasure-troves of evolutionary innovation, but most of their treasures are already extinct. As for conserving their wildlife, Turvey wonders how, without a good understanding of the local fossil record, “we even define what constitutes a ‘natural’ ecosystem, or an objective restoration target to aim for”.

A tale of islands and their ephemeral wonders would alone have made for an arresting book, but Turvey, a more-than-able raconteur, can’t resist spicing up his account with tales of Sumba’s resident mythical wild-men, the “Mili Mongga”, who, it is said, used to build walls and help out with the ploughing — until their habit of stealing food got them all killed by the infuriated human population.

Why should we pay attention to such tales? Well, Sumba is only about 50 kilometres south of Flores, where a previously unknown (and, at just over a metre tall, ridiculously small) hominin was unearthed by an Australian team in 2003.

If there were hobbits on Flores, might there have been giants on Sumba? And might surviving mili mongga still be lurking in the forests?

Turvey uses the local island legends to launch fascinating forays into the island’s history and anthropology, to explain why large animals, fetched up on islands, grow smaller, while small animals grow larger, and also to have an inordinate amount of fun, largely at his own expense.

When one villager describes a mili mongga skull as being two feet long, and its teeth “as long as a finger”, “I got the feeling,” says Turvey, ”that there might now be some exaggeration going on.” Never say never, though: soon Turvey and his long-suffering team are following gamely along on missions up crags and past crocodile-infested swamps and into holes in the ground — sometimes where other visitors, from other villages, habitually go to relieve themselves.

“There was the cave that some village kids told us contained a human skull, which turned out to be a rotten coconut under some bat dung,” Turvey recalls. “There was the cave that was sacred, which seemed to mean that no one could remember exactly where it was.”

Turvey’s more serious explorations unearthed two new mammal genera (both ancestral forms of rat). It goes without saying, I should think, that they did not bring back evidence of a new hominin. But what’s not to enjoy about a tall tale, especially when it’s used to paint such a vivid and insightful portrait of a land and its people?

“We cannot save ourselves”

Interviewing Cixin Liu for The Telegraph, 29 February 2024

Chinese writer Cixin Liu steeps his science fiction in disaster and misfortune, even as he insists he’s just playing around with ideas. His seven novels and a clutch of short stories and articles (soon to be collected in a new English translation, A View from the Stars) have made him world-famous. His most well-known novel The Three-Body Problem won the Hugo, the nearest thing science fiction has to a heavy-hitting prize, in 2015. Closer to home, he’s won the Galaxy Award, China’s most prestigious literary science-fiction award, nine times. A 2019 film adaptation of his novella “The Wandering Earth” (in which we have to propel the planet clear of a swelling sun) earned nearly half a billion dollars in the first 10 days of its release. Meanwhile The Three-Body Problem and its two sequels have sold more than eight million copies worldwide. Now they’re being adapted for the screen, and not for the first time: the first two adaptations were domestic Chinese efforts. A 2015 film was suspended during production (“No-one here had experience of productions of this scale,” says Liu, speaking over a video link from a room piled with books.) The more recent TV effort is, from what I’ve seen of it, jolly good, though it only scratches the surface of the first book.

Now streaming service Netflix is bringing Liu’s whole trilogy to a global audience. Clean behind your sofa, because you’re going to need somewhere to hide from an alien visitation quite unlike any other.

For some of us, that invasion will come almost as a relief. So many English-speaking sf writers these days spend their time bending over backwards, offering “design solutions” to real-life planetary crises, and especially to climate change. They would have you believe that science fiction is good for you.

Liu, a bona fide computer engineer in his mid-fifties, is immune to such virtue signalling. “From a technical perspective, sf cannot really help the world,” he says. “Science fiction is ephemeral, because we build it on ideas in science and technology that are always changing and improving. I suppose we might inspire people a little.”

Western media outlets tend to cast Liu — a domestic celebrity with a global reputation and a fantastic US sales record — as a put-upon and presumably reluctant spokesperson for the Chinese Communist Party. The Liu I’m speaking to is garrulous, well-read, iconoclastic, and eager. (It’s his idea that we end up speaking for nearly an hour more than scheduled.) He’s hard-headed about human frailty and global Realpolitik, and he likes shocking his audience. He believes in progress, in technology, and, yes — get ready to clutch your pearls — he believes in his country. But we’ll get to that.

We promised you disaster and misfortune. In The Three-Body Problem, the great Trisolaran Fleet has already set sail from its impossibly inhospitable homeworld orbiting three suns. (What does not kill you makes you stronger, and their madly unpredictable environment has made the Trisolarans very strong indeed.) They’ll arrive in 450 years or so — more than enough time, you would think, for us to develop technology advanced enough to repel them. That is why the Trisolarans have sent two super-intelligent proton-sized super-computers at near-light speed to Earth, to mess with our minds, muddle our reality, and drive us into self-hatred and despair. Only science can save us. Maybe.

The forthcoming Netflix adaptation is produced by Game of Thrones’s David Benioff and D.B. Weiss and True Blood’s Alexander Woo. In covering all three books, it will need to wrap itself around a conflict that lasts millennia, and realistically its characters won’t be able to live long enough to witness more than fragments of the action. The parallel with the downright deathy Game of Thrones is clear: “I watched Game of Thrones before agreeing to the adaptation,” says Liu. “I found it overwhelming — quite shocking, but in a positive way.”

By the end of its run, Game of Thrones had become as solemn as an owl, and that approach won’t work for The Three-Body Problem, which leavens its cosmic pessimism (a universe full of silent, hostile aliens, stalking their prey among the stars) with long, delightful episodes of sheer goofiness — including one about a miles-wide Trisolaran computer chip made up entirely of people in uniform, marching about, galloping up and down, frantically waving flags…

A computer chip the size of a town! A nine-dimensional supercomputer the size of a proton! How on Earth does Liu build engaging stories from such baubles? Well, says Liu, you need a particular kind of audience — one for whom anything seems possible.

“China’s developing really fast, and people are confronting opportunities and challenges that make them think about the future in a wildly imaginative and speculative way,” he explains. “When China’s pace of development slows, its science fiction will change. It’ll become more about people and their everyday experiences. It’ll become more about economics and politics, less about physics and astronomy. The same has already happened to western sf.”

Of course, it’s a moot point whether anything at all will be written by then. Liu reckons that within a generation or two, artificial intelligence will take care of all our entertainment needs. “The writers in Hollywood didn’t strike over nothing,” he observes. “All machine-made entertainment requires, alongside a few likely breakthroughs, is ever more data about what people write and consume and enjoy.” Liu, who claims to have retired and to have no skin in this game any more, points to a recent Chinese effort, the AI-authored novel Land of Memories, which won second prize in a regional sf competition. “I think I’m the final generation of writers who will create novels based purely on their own thinking, without the aid of artificial intelligence,” he says. “The next generation will use AI as an always-on assistant. The generation after that won’t write.”

Perhaps he’s being mischievous (a strong and ever-present possibility). He may just be spinning some grand-sounding principle out of his own charmingly modest self-estimate. “I’m glad people like my work,” he says, “but I doubt I’ll be remembered even ten years from now. I’ve not written very much. And the imagination I’ve been able to bring to bear on my work is not exceptional.” His list of influences is long. His father bought him Wells and Verne in translation. Much else, including Kurt Vonnegut and Ray Bradbury, required translating word for word with a dictionary. “As an sf writer, I’m optimistic about our future,” Liu says. “The resources in our solar system alone can feed about 100,000 planet Earths. Our future is potentially limitless — even within our current neighbourhood.”

Wrapping our heads around the scales involved is tricky, though. “The efforts countries are taking now to get off-world are definitely meaningful,” he says, “but they’re not very realistic. We have big ideas, and Elon Musk has some exciting propulsion technology, but the economic base for space exploration just isn’t there. And this matters, because visiting neighbouring planets is a huge endeavour, one that makes the Apollo missions of the Sixties and Seventies look like a fast train ride.”

Underneath such measured optimism lurks a pessimistic view of our future on Earth. “More and more people are getting to the point where they’re happy with what they’ve got,” he complains. “They’re comfortable. They don’t want to make any more progress. They don’t want to push any harder. And yet the Earth is pretty messed up. If we don’t get into space, soon we’re not going to have anywhere to live at all.”

The trouble with writing science fiction is that everyone expects you have an instant answer to everything. Back in June 2019, a New Yorker interviewer asked him what he thought of the Uighurs (he replied: a bunch of terrorists) and their treatment at the hands of the Chinese government (he replied: firm but fair). The following year some Republican senators in the US tried to shame Netflix into cancelling The Three-Body Problem. Netflix pointed out (with some force) that the show was Benioff and Weiss and Woo’s baby, not Liu’s. A more precious writer might have taken offence, but Liu thinks Netflix’s response was spot-on. ““Neither Netflix nor I wanted to think about these issues together,” he says.

And it doesn’t do much good to spin his expression of mainstream public opinion in China (however much we deplore it) into some specious “parroting [of] dangerous CCP propaganda”. The Chinese state is monolithic, but it’s not that monolithic — witness the popular success of Liu’s own The Three Body Problem, in which a girl sees her father beaten to death by a fourteen-year-old Red Guard during the Cultural Revolution, grows embittered during what she expects will be a lifetime’s state imprisonment, and goes on to betray the entire human race, telling the alien invaders, “We cannot save ourselves.”

Meanwhile, Liu has learned to be ameliatory. In a nod to Steven Pinker’s 2011 book The Better Angels of Our Nature, he points out that while wars continue around the globe, the bloodshed generated by warfare has been declining for decades. He imagines a world of ever-growing moderation — even the eventual melting away of the nation state.

When needled, he goes so far as to be realistic: “No system suits all. Governments are shaped by history, culture, the economy — it’s pointless to argue that one system is better than another. The best you can hope for is that they each moderate whatever excesses they throw up. People are not and never have been free to do anything they want, and people’s idea of what constitutes freedom changes, depending on what emergency they’re having to handle.”

And our biggest emergency right now? Liu picks the rise of artificial intelligence, not because our prospects are so obviously dismal (though killer robots are a worry), but because mismanaging AI would be humanity’s biggest own goal ever: destroyed by the very technology that could have taken us to the stars!

Ungoverned AI could quite easily drive a generation to rebel against technology itself. “AI has been taking over lots of peoples’ jobs, and these aren’t simple jobs, these are what highly educated people expected to spend lifetimes getting good at. The employment rate in China isn’t so good right now. Couple that with badly managed roll-outs of AI, and you’ve got frustration and chaos and people wanting to destroy the machines, just as they did at the beginning of the industrial revolution.”

Once again we find ourselves in a dark place. But then, what did you expect from a science fiction writer? They sparkle best in the dark. And for those who don’t yet know his work, Liu is pleased, so far, with Netflix’s version of his signature tale of interstellar terror, even if its westernisation does baffle him at times.

“All these characters of mine that were scientists and engineers,” he sighs. “They’re all politicians now. What’s that about?”

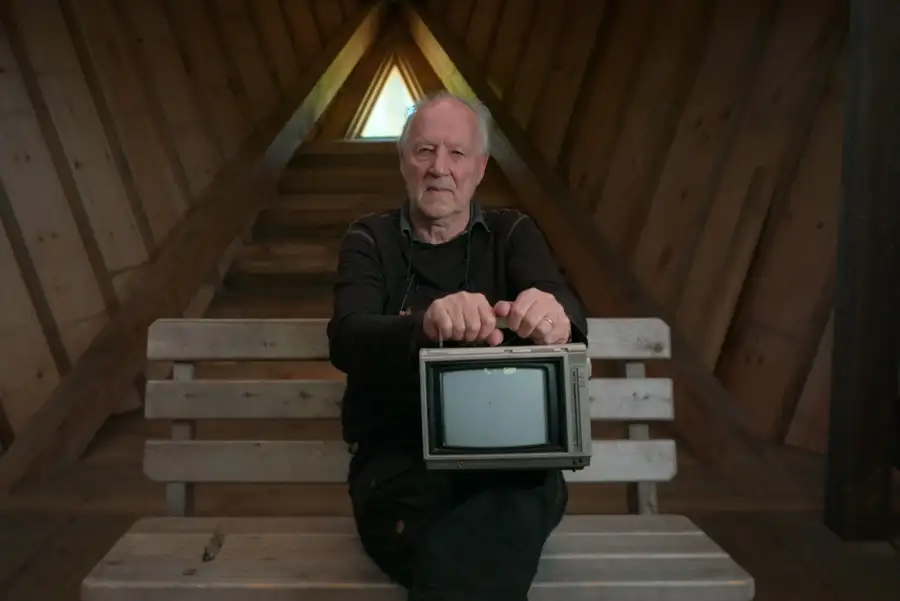

A carpenter doesn’t sit on his shavings

Watching Ian Cheney’s The Arc of Oblivion for New Scientist, 28 February 2024

“Humans don’t like forgetting,” says an archivist from the Al Ahmed Mahmoud library in Chinguetti. Located on an old pilgrim route to Mecca, Chinguetti in Mauretania is now disappearing under the spreading Sahara. And not for the first time: there have been two previous cities on this site, the first built in 777 AD, and both have vanished beneath the dunes.

Ian Cheney, a documentary maker from Maine in the US, visits the Arabo-Berber libraries of Chinguetti towards the end of a film that’s been all about what we try to preserve and hang on to, born as we are into a universe that seems willfully determined to forget and erase our fragile leavings.

You can understand why Cheney becomes anxious around issues of longevity and preservation: as a 21st-century film-maker, he’s having to commit his life’s work to digital media that are less durable and more prone to obsolescence than the media of yesteryear: celluloid, or paper, or ceramic.

Nonetheless, having opened his film with the question “What from this world is worth saving?”, Cheney ends up asking a quite different question: “Are we insane to imagine anything can last?”

“Humans don’t like forgetting” may, in the end, be the best reason we can offer for why we frantically attempt hold time and decay at bay.

This film is built on a pun. We see Cheney and various neighbours and family friends building an ark-shaped barn in his parents’ woodland, and made from his parents’ lumber. It’s big enough, he calculates that if all human knowledge were reduced to test-tubes of encoded DNA, he could just about close the barn doors on it all.

(The ability to store information as DNA is one of the wilder detours in a film that delights in leaping down intellectual and poetic rabbit holes. The friability of memory, music and memory, ghost stories, floods and hurricanes — the list of subjects is long but, to Cheney’s credit, it never feels long).

Alongside that Ark in the woods, there is also an arc — the “arc of oblivion” that gives this film its title, and carrying the viewer away from anxiety, and into a more contemplative and accepting relationship with time. Perhaps it is enough, in this life, for us to be simply passing through, and taking in the scenery.

Executive producer Werner Herzog, a veteran filmmaker, appears towards the end of the movie. Asked why he destroys all the preparatory materials generated by his many projects, he replies “The carpenter doesn‘t sit on his shavings, either.”

This is good philosophy, and sensible practice for an artist — but it’s rather cold comfort for the rest of us. At least while we’re saving things we might be able to forget, for a moment, about oblivion.

If human happiness is what you want, then the trick may be to collect for the pure pleasure of collecting. Even as it struggles to preserve Arabo-Berber texts that date back to the time of the Prophet, the Al Ahmed Mahmoud library finds time to accept and catalogue books of all kinds donated by people who are simply passing through. We also meet speliologist Bogdan Onuc, who traces the histories of Majorcan caves by studying their layered deposits of bat guano (and all the while the caves’ unique interiors are being melted away by the carbonic acid generated by visitors’ breaths…) But Onuc still finds time to collect ornamental hedgehogs and owls.

Cheney’s cast of friends and acquaintances is long, and the film’s discursive, matesy approach to their experiences — losing photographs, burying artworks, singing to remember, singing to forget — teeters at times towards the mawkish. The Arc of Oblivion remains, nonetheless, an enjoyable and often moving meditation on the pleasures and perils of the archive.

A safe pair of hands

Watching Denis Villeneuve’s Dune Part 2 for New Scientist, 23 February 2024

So here’s where we’re at, in the concluding half of Denis Villeneuve’s adaptation of Dune:

Cast into the wilderness of planet Arrakis by invading House Harkonnen, young Paul Atreides (Timothee Chalamet) learns the ways of the desert, embraces his genetic and political destiny, and becomes in one swoop a focus for fanaticism and (with an eye to a third film, an adaptation of author Frank Herbert’s sequel, Dune Messiah) the scourge of the Universe.

From Alejandro Jodorowosky’s mid-1970s effort, which never bore fruit (but at least gave Swiss artist H.R. Giger his entrée into movies and, ultimately, Alien), and from David Lynch’s more-than-four-hour farrago, savagely edited prior to its 1984 release into something approaching (but only approaching) coherence, many assumed that Dune is an epic too vast to be easily filmed. Throw resources at it, goes the logic, and it will eventually crumble to your will.

That this is precisely the wrong lesson to draw was perfectly demonstrated by John Harrison’s 2000 miniseries for the Sci Fi Channel and its sequel, Children of Dune (2003) — both absurdly under-resourced, but both offering satisfying stories that the fans lapped up, even if the critics didn’t.

Now we have Villeneuve’s effort, and like his Blade Runner 2049, it uses visual stimulation to hide the gaping holes in its plot.

Yes, the story of Dune is epic. But it is also, in the full meaning of the word, weird. It’s about a human empire that’s achieved cosmic scale, and all without the help of computers, destroyed long ago in some shadowy “Butlerian Jihad”. In doing so it has bred, drugged and otherwise warped individual humans into becoming something very like Gods. In conquering space, humanity teeters on the brink of attaining power over time. The “spice” mined on planet Arrakis is not just a rare resource over which great houses fight, but the spiritual gateway that makes humanity, in this far future, viable in the first place.

Leave these elements undeveloped (or, as here, entirely ignored) and you’re left with an awful lot of desert to fill with battles, sword play, explosions, crowd scenes, and sandworms — and here an as yet unwritten rule of SFX cinematography comes into play, because I swear the more these wrigglers cost, the sillier they get. (If that’s the sandworm’s front end on those posters, I shudder to think what the back end looks like.) Your ears will ring, your heart will thunder, and by morning the entire experience will have evaporated, like a long (2-hour 46-minute) fever dream.

As Beast Raban, Dave Bautista outperforms the rest of the cast to a degree that is embarrassing. The Beast’s an Harkonnen, an alpha predator in this grim universe, and yet Bautista is the only actor here capable of portraying fear. Javier Bardem’s desert leader Stilgar is played for laughs (but let’s face it, in the entire history of cinema, name one desert leader that hasn’t been). Timothee Chalamet stands still in front of the camera. His love interest, played by Zendaya, scowls and growls like Bert Lahr’s Cowardly Lion in the Wizard of Oz.

Dune Part Two is an expensive (USD 190 million) film which has had the decency to put much of its budget in front of the camera. This makes it watchable, enjoyable, and at times even thrilling. Making a good Dune movie, though, requires a certain eccentricity. Villeneuve is that deadening thing, “a safe pair of hands”.

More believable than the triumph

20:05 GMT on 20 July 1969: astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin are aboard Apollo l1’s Lunar Command Module, dropping steadily towards the lunar surface in humankind’s first attempt to visit another world.

“Drifting to the right a little,” Buzz remarks — and then an alarm goes off, and then another, and another, until at last the transmission breaks down.

The next thing we see is a desk set in front of a blue curtain, and flanked by flags: the Stars and Stripes, and the Presidential seal. Richard Nixon, the US President, takes his seat and catches the eye of figures hovering off-screen: is everything ready?

And so he begins; it’s a speech no one can or will forget. It was written by his speechwriter, William Safire, as a contingency in the event that Buzz and Neil land on the Moon in a way that leaves them alive but doomed, stranded without hope of rescue in the Sea of Tranquility.

“These brave men… know that there is no hope for their recovery.” Nixon swallows hard. “But they also know that there is hope for Mankind in their sacrifice.”

From 17 February, Richard Nixon’s speech will play to visitors to the Sainsbury Centre in Norwich. They will watch it from the comfort of a 1960s-era sofa, in a living room decked out in such a way as to transport them back to that day, in June 1969, when two heroes found themselves doomed and alone and sure to die on the Moon.

Confronted with Nixon struggling to control his emotions on a period TV, they may well ask themselves if what they are seeing is real. The props are real, and so is the speech, marking and mourning the death of two American heroes. Richard Nixon is real, or as real as anyone can be on TV. His voice and gestures are his own (albeit — and we’ll come to this in a moment — strung together by generative computer algorithms).

Will anyone be fooled?

Not me. I can remember Apollo 11’s successful landing, and the crew’s triumphant return to Earth less than a week later, on 24 July. But, hang on — what, exactly, do I remember? I was two. If my parents had told me, over and over, that they had sat me down in front of TV coverage of the Kennedy assassination, I would probably have come to believe that, too. Memory is unreliable, and people are suggestible.

Jago Cooper includes the installation In Event of Moon Disaster in the Sainsbury Centre’s exhibition “What Is Truth”. Cooper, who directs the centre, wasn’t even born when Apollo 11 rose from the launchpad. Neither were the two filmmakers, Halsey Burgund and Francesca Panetta, who won a 2021 Emmy for In Event Of Moon Disaster in the category of Interactive Media Documentary. The bottom line here seems to be: the past exists only because we trust what others say about it.

Other exhibits in the “What is Truth?” season will come at the same territory from different angles. There are artworks about time and artworks about identity. In May, an exhibition entitled The Camera Never Lies uses war photography from a private collection, The Incite Project, to reveal how a few handfuls of images have shaped our narratives of conflict. This is the other thing to remember, as we contemplate a world awash with deepfakes and avatars: the truth has always been up for grabs.

Sound artist Halsey Burgund and artist-technologist Francesca Panetta recruited experts in Israel and Ukraine to help realise In Event Of Moon Disaster. Actor Louis Wheeler spent days in a studio, enacting Nixon’s speech; the President’s face, posture and mannerisms were assembled from archive footage of a speech about Vietnam.

President Nixon’s counterfactual TV eulogy was produced by the MIT Center for Advanced Virtuality to highlight the malleability of digital images. It’s been doing the rounds of art galleries and tech websites since 2019, and times have moved on to some degree. Utter the word “deepfake” today and you’re less likely to conjure up images of a devastated Richard Nixon as gossip about those pornographic deepfake images of Taylor Swift, viewed 27 million times in 19 hours when they were circulated this January on Twitter.

No-one imagines for second that Swift had anything to do with them, of course, so let’s be positive here: MIT’s message about not believing everything you see is getting through.

As a film about deepfakes, In Event of Moon Disaster is strangely reassuring. It’s a work of genuine creative brilliance. It’s playful: we feel warmer towards Richard Nixon in this difficult fictional moment than we probably ever felt about him in life. It’s educational: the speech, though it never had to be delivered (thank God), is real enough, an historical document that reveals how much was at stake on that day. And in a twisted way, the film is immensely respectful, singing the praises of extraordinary men in terms only tragedy can adequately articulate.

As a film about the Moon, though, In Event of Moon Disaster is a very different kettle of fish and frankly disturbing. You can’t help but feel, having watched it, that Burgund and Panetta’s synthetic moon disaster is more believable than Apollo’s actual, historical triumph.

The novelist Norman Mailer observed early on that “in another couple of years there will be people arguing in bars about whether anyone even went to the Moon.” And so it came to pass: claims that the moon landings were fake began the moment the Apollo missions ended in 1972.

The show’s curator Jago Cooper has a theory about this: “The Moon is such a weird bloody thing,” he says. “The idea that we merely pretended to walk about there is more believable than what actually happened. That’s the thing about our relationship with what we’re told: it has to be believable within our lived experience, or we start driving wedges into it that undermine its credibility.”

This raises a nasty possibility: that the more enormous our adventures, the less likely we are to believe them; and the crazier our world, the less attention we’ll pay to it. “Humankind cannot bear very much reality” said TS Eliot, and maybe we’re beginning to understand why.

For a start, we cannot bear too much information. The more we’re told about the world, the more we search for things that are familiar. In an essay accompanying the exhibition, curator Paul Luckraft finds us in thrall to confirmation bias “because we can’t see what’s new in the dizzying amount of text, image, video and audio fragments available to us.”

The deluge of information brought about by digital culture is already being weaponised — witness Trump’s former chief strategist Steve Bannon, who observed in 2018, ‘The real opposition is the media. And the way to deal with them is to flood the zone with shit.”

Even more disturbing: the world of shifting appearances ushered in by Bannon, Trump, Putin et al. might be the saving of us. In a recent book about the future of nuclear warfare, Deterrence under Uncertainty, RAND policy researcher Edward Geist conjures up a likely media-saturated future in which we all know full well that appearances are deceptive, but no-one has the faintest idea what is actually going on. Belligerents in such a world would never have to fire a shot in anger, says Geist, merely persuade the enemy that their adversary’s values are better than their own.

“Tricky Dick” Nixon would flourish in such a hyper-paranoid world, but then, so might we all. Imagine that perpetual peace is ours for the taking — so long as we abandon the faith in facts that put men on the Moon!

Fifty years ago you’d have struggled to find a anyone casting doubt on NASA’s achievement, that day in July 1969. Fifty years later, a YouGov poll found sixteen per cent of the British public believed the moon landing most likely never happened.

Deepfakes themselves aren’t the cause of such incredulity, but they have the potential to exacerbate it immeasurably — and this, says Halsey Burgund, is why he and Francesca Panetta were inspired to make In Event of Moon Disaster. “The hope of the project is to provide some simple awareness of this kind of technology, its ubiquity and out-there-ness,” he explains. “If we’ve made an aesthetically satisfying and emotional piece, so much the better — it’ll help people internalise the challenges facing us right now.” Though bullish in defence of the technology’s artistic possibilities, Burgund concedes that the harms it can wreak are real, and can be distributed at scale. (Ask Taylor Swift.) “It’s not as though intelligent people aren’t addressing these problems,” Burgund says. “But it takes a lot of time — and society can’t change that quickly.”

Infectious architecture

Visiting Small Spaces in the City at ROCA London Gallery for New Scientist, 12 February 2024

“Cook’s at it again,” reads one Antarctic station log entry from the 1970s. “Threw a lemon pie and cookies all over the galley… then went to his room for a couple of days and wouldn’t come out… no clear reason… probably antarcticitis catching up…”

And now it’s not just the behavioural challenges of small spaces that give designers pause, as they contemplate our ever-more constrained future. There’s our health to consider. Damp, mould and other problems endemic to small spaces are not so easily addressed, especially in cities where throwing open the windows and letting in air filled with particulates, spores, moulds and pollen can make matters measurably worse. In February 2013, nine-year-old Londoner Ella Kissi-Debrah became the first person in the UK to have air pollution listed as a cause of death. (Meanwhile a report by the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors published in 2017 reckons the average new home in London has shrunk by 20% since 2000.)

How are we to live and thrive in tiny spaces? Curator Clare Farrow’s new exhibition at ROCA London Gallery brings together ideas amd designs from around the world. She’s arranged an interview with Hong Kong-based Gary Chang, whose 32 square metre apartment currently boasts 24 different “rooms”, assembled by manoeuvring a system of sliding walls, and commissioned a film in which William Bracewell, a principal with London’s Royal Ballet, performs (somehow) in the tiny dressing room-cum-costume store he shares with two other dancers.

She’s also, for at least a couple of days (dates to be announced), got Richard Beckett, an architect based at the Bartlett School booth at the centre of the exhibition, to bring attention to the health challenges of “studio living”.

Beckett reckons we should be using microbes to make our buildings healthier. As he explains in a forthcoming paper, “As the built environment is now the predominant habitat of the human, the microbes that are present in buildings are of fundamental importance.” Alas, contemporary buildings are microbial wastelands: dry, nutrient poor and sterile.

In 2020 Beckett won an award from the Royal Institute of British Architects for embedding “beneficial bacteria” into ceramic and concrete surfaces. At ROCA he’ll be sitting in a booth dosed with this material, while Matthew Reeves, an immunologist at University College, London, uses regular blood samples to measure whether tile-borne pro-biotic species can survive long enough, and spread easily enough, to become part of Beckett’s personal microbiome.

“The official study will have to take place in a more controlled way after the exhibition’s finished,” Beckett admits, “but at least my spell in the booth is a bit of theatre to demonstrate what we’re up to.”

Explaining the work is vital, since it runs so counter to prevailing nostrums concerning hygiene and cleanliness. “One immediate application of our work is in hospitals and care homes,” Beckett says, “where super-sterile environments have ended up providing ideal breeding conditions for antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Of course the first question we’ll be asked is, ‘How do you clean them?’”

Beckett’s booth is tiled with what look like worm casts: these are 3D printed ceramic tiles, lightly baked and designed to shed bacteria into the air with every passing motion. Their peculiar surface texture is tantalising on purpose: touching them helps spread the healthy biota, filling sterile interiors (this is the plan) with sustainable microbial ecosystems.

“There’s still much that we don’t know about how microbes interact with each other and with our environment,” says Beckett, who is realistic about the time it will take for us to abandon the twentieth century’s wipe-clean aesthetic, and embrace the stain. “This work will prove its worth in small interiors first.”

Making time for mistakes

If you believe there really is no time for political mistakes on some crucial issue — climate change, say, or the threat of nuclear annihilation — then why should you accept a leader you did not vote for, or endorse an election result you disagree with? Jonathan White, a political sociologist at the London School of Economics, has written a short book about a coming crisis that democratic politics, he argues, cannot possibly accommodate: the world’s most technologically advanced democracies are losing their faith in the future.

This is not a new thought. In her 2007 book The Shock Doctrine Naomi Klein predicted how governments geared to crisis management would turn ever more dictatorial as their citizens grew ever more distracted and malleable. In the Long Run White is less alarmist but more pessimistic, showing how liberal democracy blossoms, matures, and ultimately shrivels through the way it imagines its own future. Can it survive in the world where high-school students are saying things like ‘I don’t understand why I should be in school if the world is burning’?

A broken constitution, an electorate that’s ignorant or misguided, institutions that are moribund and full of the same old faces, year after year — these are not nearly the serious problems for democracy they appear to be, says White: none of them undermines the ideal, so long as we believe that there’s a process of self-correction going on.

Democracy is predicated on an idea of improvability. It is, says White, “a future-oriented form, always necessarily unfinished”. The health of a democracy lies not in what it thinks of itself now, but in what hopes it has for its future. A few pages on France’s Third Republic — a democratic experiment that, from latter part of the 19th century to the first decades of the 20th, lurched through countless crises and 103 separate cabinets to become the parliamentary triumph of its age — would have made a wonderful digression here, but this is not White’s method. In the Long Run relies more on pithy argument than on historical colour, offering us an exhilarating if sometimes dizzingly abstract historical fly-through of the democratic experiment.

Democracy arose as an idea in the Enlightenment, via the evolution of literary Utopias. White pays special attention to Louis-Sébastien Mercier’s 1771 novel The Year 2440: A Dream if Ever There Was One, for dreaming up institutions that are not just someone’s good idea, but actual extensions of the people’s will.

Operating increasingly industrialised democracies over the course of the 19th century created levels of technocratic management that inevitably got in the way of the popular will. When that process came to a crisis in the early years of the 20th century, much of Europe faced a choice between command-and-control totalitarianism, and beserk fascist populism.

And then fascism, in its determination to remain responsive and intuitive to the people’s will, evolved into Nazism, “an ideology that was always seeking to shrug itself off,” White remarks; “an -ism that could affirm nothing stable, even about itself”. Its disastrous legacy spurred post-war efforts to constrain the future once more, “subordinating politics to economics in the name of stability.” With this insightful flourish, the reader is sent reeling into the maw of the Cold War decades, which turned politics into a science and turned our tomorrows into classifiable resources and tools of competitive advantage.

White writes well about 20th-century ideologies and their endlessly postponed utopias. The blandishments of Stalin and Mao and other socialist dictators hardly need glossing. Mind you, capitalism itself is just as anchored in the notion of jam tomorrow: what else but a faith in the infinitely improvable future could have us replacing our perfectly serviceable smartphones, year after year after year?

And so to the present: has runaway consumerism now brought us to the brink of annihilation, as the Greta Thunbergs of this world claim? For White’s purposes here, the truth of this claim matters less than its effect. Given climate change, spiralling inequality, and the spectres of AI-driven obsolescence, worsening pandemics and even nuclear annihilation, who really believes tomorrow will look anything like today?

How might democracy survive its own obsession with catastrophe? It is essential, White says, “not to lose sight of the more distant horizons on which progressive interventions depend.” But this is less a serious solution, more an act of denial. White may not want to grasp the nettle, but his readers surely will: by his logic (and it seems ungainsayable), the longer the present moment lasts, the worse it’ll be for democracy. He may not have meant this, but White has written a very frightening book.

A snapshot of how a city survives

Watching Occupied City by Steve McQueen for New Scientist, 31 January 2024

Artist and director Steve McQueen’s new documentary unfolds at a leisurely pace. Viewers will be glad of the 15-minute intermission baked into the footage, some two hours into the film’s over-four-hour runtime. If you need to make a fast getaway, now’s your chance — but I’ll bet the farm that you’ll return to your seat.

McQueen, a Londoner, now lives in Amsterdam with his wife Bianca Stigter, and Occupied City is based on Atlas of an Occupied City, Amsterdam 1940-1945, Stigter’s monumental account of the city’s wartime Nazi occupation.

Narrator Melanie Hyams recites the book’s gazetteer of the occupation, address by address, while McQueen films each place as it appears today. Here is the street market where they used to hand out Star of David patches to the city’s Jews. (60,000 of the city’s 80,000 Jews were expelled during the second world war, and almost all of those taken were subsequently murdered.) Outside this now busy cafe, someone once found a potato in the gutter, and burned a book to cook it. At this site, in the “Hunger Winter” of 1944-1945, the diving boards at a since demolished swimming pool were chopped up for firewood. Here, a family was saved. There, a resistance worker was betrayed.

Though many of the buildings still stand, the word “demolished” recurs again and again, and it’s rare that McQueen’s street photography does not capture some new bit of demolition or construction. Amsterdam does not stay still. So how does a living, changing city remember itself?

There are acts of commemoration of course — among them a royal visit to a Jewish holocaust memorial, and a municipal apology for the predations of the city’s participation in the slave trade. But a city’s identity runs deeper than memorials surely? Do drinkers at this bar remember the Jews who were beaten outside their windows? Do the occupants of that flat know about the previous owners, a Jewish couple who committed suicide, sooner than live under Nazi occupation?

Stigter’s Atlas is an act of remembrance. Her husband’s film is different: a snapshot of how a city survives being managed and choreographed, corralled and contained. Some of Occupied City was shot during a five-week Covid lockdown. We see the modern city beset by plague, even as we hear of how, in the past, it was brought near to destruction by foreign occupation. McQueen draws no facile parallels here. Rather, we’re encouraged to see that restrictions are restrictions and curfews are curfews, whoever imposes them, and whatever their motives. What’s interesting is to see how people react to civil control, as it becomes (whether through necessity or not) increasingly heavy-handed.

At a big anti-fascist rally, conducted outside the city’s Concertgebouw concert hall, a speaker announces that “Democracy is more fragile then ever.”

Is it, though? Occupied City would suggest otherwise. It’s a film full of ordinary people, eating, playing guitar (badly), playing videogames, smoking, sheltering from the rain, and walking dogs in the mist. It’s a film about citizenry who survived one lethal onslaught now handling another one — not so obviously violent, perhaps, but pervasive and undoubtedly lethal.

Occupied City is not about what people believe. It’s about how they behave. And, lo and behold, people are mostly decent. Leave us alone, and we’ll go tobogganing, or skating, or cycling, or dancing. We’re civically minded by nature. The nightmares, the riots, the beating and betrayals — these only surface when you start putting us in boxes.

A spirit of anarchism pervades this monumental movie. It’s not anti-authoritarian, exactly; it’s just not that interested in what authority thinks. Reeling as we are from the dislocations of Covid, it’s a comfort, and a challenge, to be reminded that cities are, when you come down to it, nothing more than their people.