Is there such a thing as intellectual property? Once you’ve had an idea, and disseminated it through manuscript or sculpture, performance or song, is it still yours?

The ancients thought so. Long before copyright was ever dreamed of, honour codes policed the use and reuse of the work of poets and playwrights, and throughout the history of the arts, proven acts of plagiarism have brought down reputational damage sufficient to put careless and malign scribblers and daubers out of business.

At the same time, it has generally been acceptable to repurpose a work, for satire or even for further development. Pamela had many more adventures outside of Samuel Richardson’s novel than within it, though (significantly) it is Richardson’s original novel that people still buy.

No one in the history of the world has ever argued that artists should not be remunerated. Nor has the difference between an ingenious repurposing of material and its fraudulent copy ever been particularly hard to spot. And though there will always be edge cases, that, surely, is where the law steps in, codifying natural justice in a way useful to sincere litigants. So you would think.

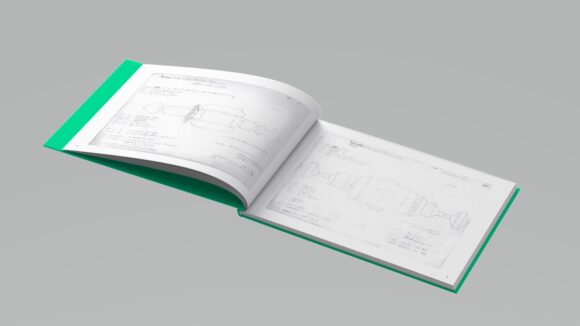

Alexandre Montagu, an intellectual property lawyer, and David Bellos, a literary academic, think otherwise. Their forensic, fascinating history of copyright reveals a highly contingent history — full of ambiguity and verbal sophistry, as meanings shift and interests evolve.

The idea of copyright arose from state control of the media. This arose in response to the advent of cheap unregulated printing, which had fostered the creation and circulation of “scandalous, false and politically dangerous trash”. (That social media have dragged us back to the 17th century is a point that hardly needs rehearsing.)

In England, the Licensing of the Press Act of 1662 gave the Stationer’s Company an exclusive right to publish books. Wisely, such a draconian measure expired after a set term, and in 1710 the Statute of Anne established a rather more author-friendly arrangement. Authors would “own” their own work for 28 years — they would possess it, and they would have to answer for it. They could also assign their rights to others to see that this work was disseminated. Publishers, being publishers, assumed such rights then belonged to them in perpetuity, making what Daniel Defoe called a “miserable Havock” of authors’ rights law that pertains to this day.

True copyright was introduced in 1774, and the term over which an author has rights over their own work has been extended year on year; in most territories, it now covers the author’s lifetime plus seventy years. The definition of an “author” has been widened, too, to include sculptors, song-writers, furniture makers, software engineers, calico printers — and corporations.

Copyright is like the cute baby chimp you bought at the fair that grows into a fully grown chimpanzee that rips your kid’s arms off. Recent decades, the authors claim, “have turned copyright into a legal machine that restores to modern owners of content the rights and powers that eighteenth-century publishers lost, and grants them wider rights than their predecessors ever thought of asking for.”

And don’t imagine for a second that these owners are artists. Bellos and Montagu trace all the many ways contemporary creatives and their families are forced into surrendering their rights to an industry that now controls between 8 and 12 per cent of the US economy and is, the authors say, “a major engine of inequality in the twenty-first century”.

Few predicted that 18th-century copyright, there to protect the interests of widows and orphans, would have evolved into an industry that in 1996 seriously tried to charge girl-scout camp organisers for singing “God Bless America” around the campfire; and actually has managed to assert in court that acts of singular human genius are responsible for everyday items ranging from sporks to inflatable banana costumes.

Modern copyright’s ability to sequester and exploit creations of every kind for three or four generations is, the authors say, the engine driving “the biggest money machine the world has seen”, and one of the more disturbing aspects of this development is the lack of accompanying public interest and engagement.

Bellos and Montagu have extracted an enormous amount of fun out of their subject, and have sauced their sardonic and playful prose with buckets full of meticulously argued bile. What’s not to love about a work of legal scholarship that dreams up “a song-and-dance number based on a film scene in Gone with the Wind performed in the Palace of Culture in Petropavlovsk” and how it “might well infringe The Rights Of The American Trust Bank Company”?

This is not a book about “information wanting to be free” or any such claptrap. It is about a whole legal field failing in its mandate, and about how easily the current dispensation around intellectual property could come crumbling down. It is also about how commonly held ideas of propriety and justice might build something better in place of our current ideas of “I.P.”. Bellos and Montagu’s challenge to intellectual property law is by turns sobering and cheering: doing better than this will hardly be rocket science.